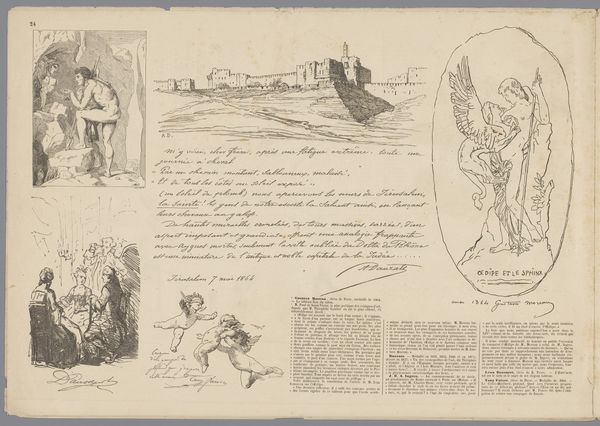

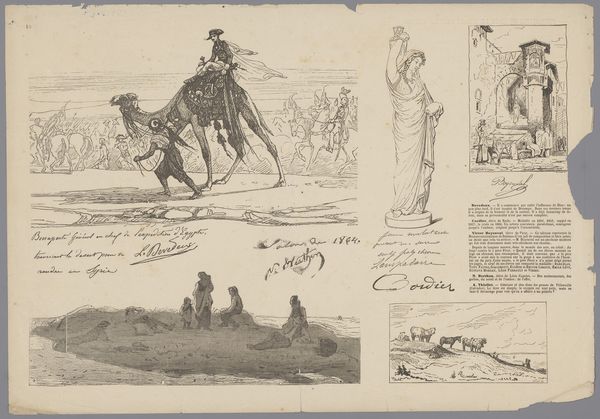

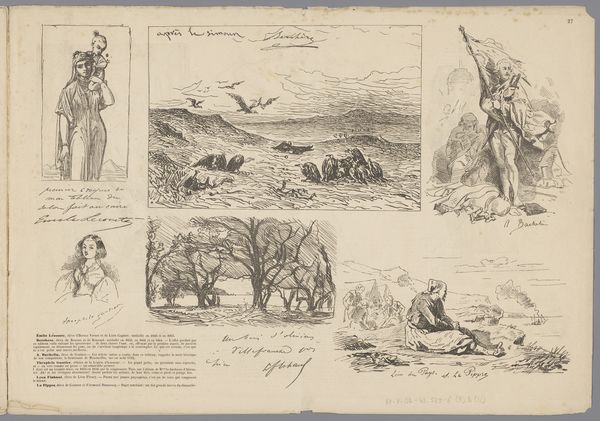

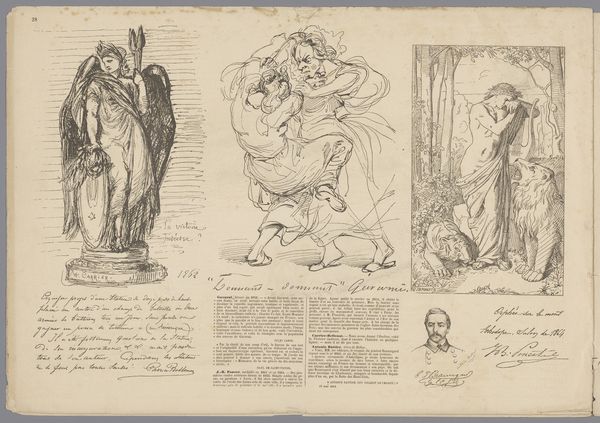

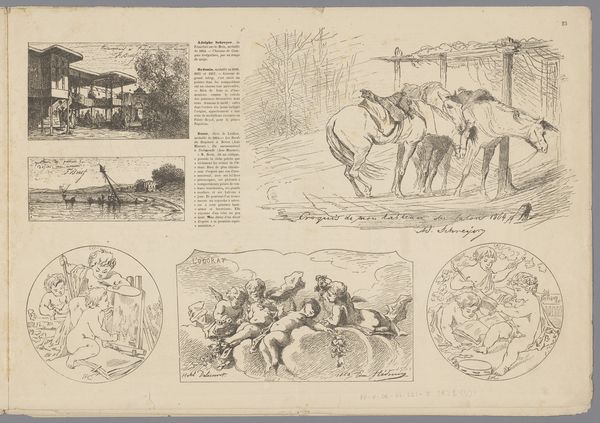

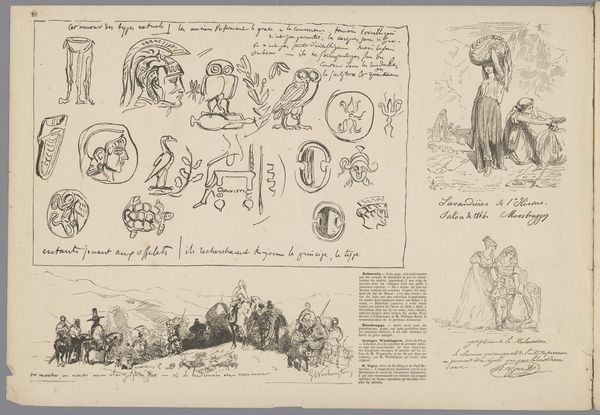

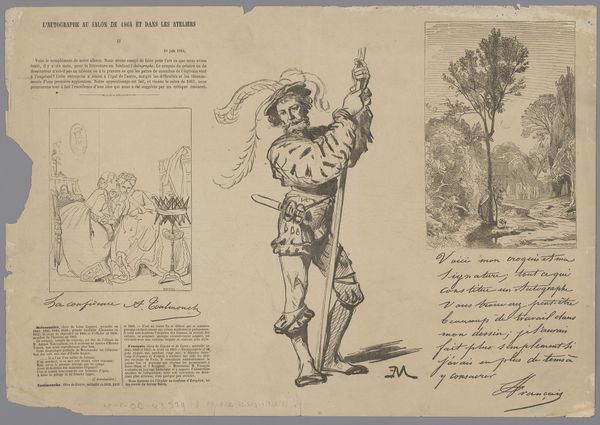

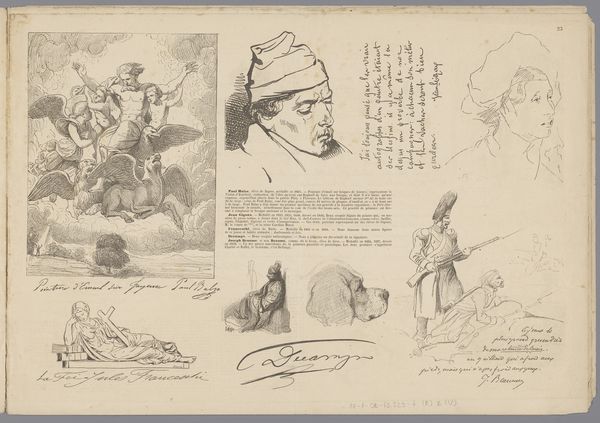

Twee engelen, een moeder met kind, Daniël in de leeuwenkuil en landschap met paarden Possibly 1864 - 1866

0:00

0:00

drawing, paper, ink

#

drawing

#

landscape

#

figuration

#

paper

#

ink

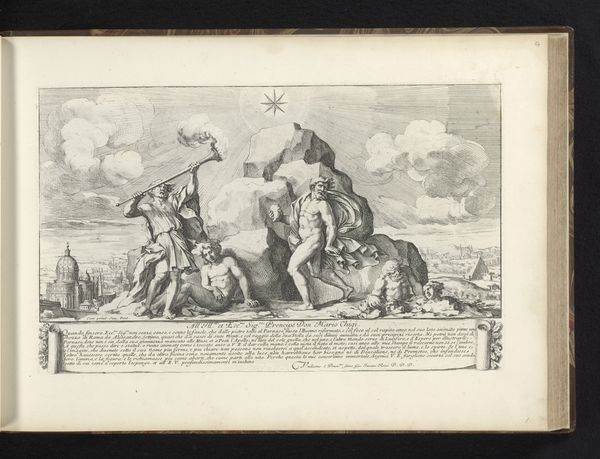

Dimensions: height 327 mm, width 468 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

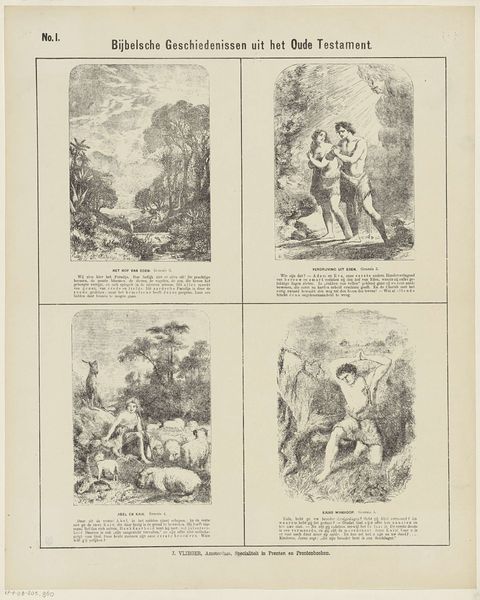

Curator: This fascinating ink drawing on paper is titled "Twee engelen, een moeder met kind, Daniël in de leeuwenkuil en landschap met paarden", possibly created between 1864 and 1866 by Firmin Gillot. What catches your eye initially? Editor: The sheer eclecticism! It's like a sketchbook page overflowing with different concepts and sketches. The "Daniel in the Lions' Den" scene, with the figure standing defiantly amongst the lions, dominates, and the tonal contrasts really make the drama pop. Curator: I agree, the visual density is striking. The process itself suggests a copyist’s endeavor. This page might represent Gillot’s exploration and recording of other works. Each motif likely originates in existing paintings, sculptures, or printed imagery circulating within nineteenth-century French visual culture. The angels, mother and child, lions—these resonate with themes found everywhere from academic painting to popular illustration. Editor: The layout leads my eye to examine the lines and form used to represent them. Consider, for example, the musculature and drapery of the angels, and their contrasted composition compared to the angular planes of the cliffs and tightly compacted elephants in the landscape at the bottom. Semiotically, what do they tell us about the artistic culture from whence it emerged? Curator: It emphasizes a tension between tradition and industrial modernity. On the one hand, these biblical and allegorical scenes perpetuate dominant ideologies. Yet, by reproducing and compiling them in this format, Gillot arguably democratizes these images and, through printing techniques, puts them into wider circulation, thus potentially transforming their reception by different classes and contexts. The reproductive means shape artistic production and influence our understanding of subjecthood and even belief. Editor: But it is the symbolic framework Gillot builds on that defines it. Daniel represents faith in the face of persecution; the angels, divine protection; and even the mundane landscape speaks to the wonder of the natural world. Gillot’s masterful manipulation of ink captures these subtle yet profound meanings. Curator: And how it reflects, then, upon shifts in print and media economies shaping conceptions of art as both labor and intellectual exercise during a crucial stage in modernity! Ultimately, I appreciate it most as a valuable trace of the social contexts defining 19th-century image-making. Editor: Indeed, these composite narratives leave me with an intense yet fleeting appreciation for the confluence of art, meaning, and pure artistry!

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.