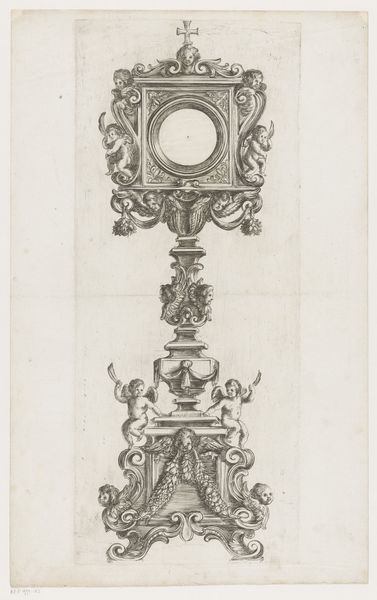

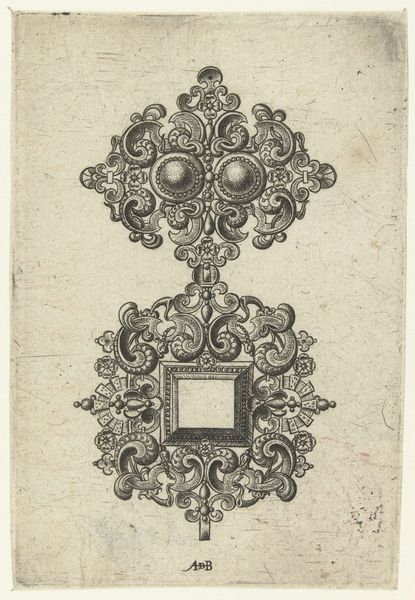

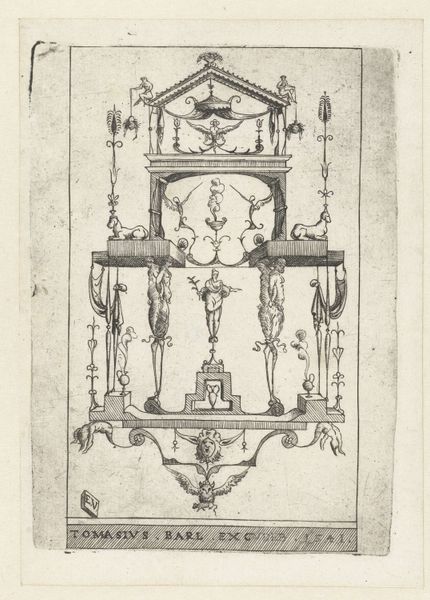

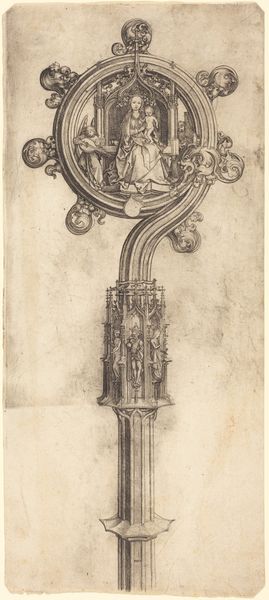

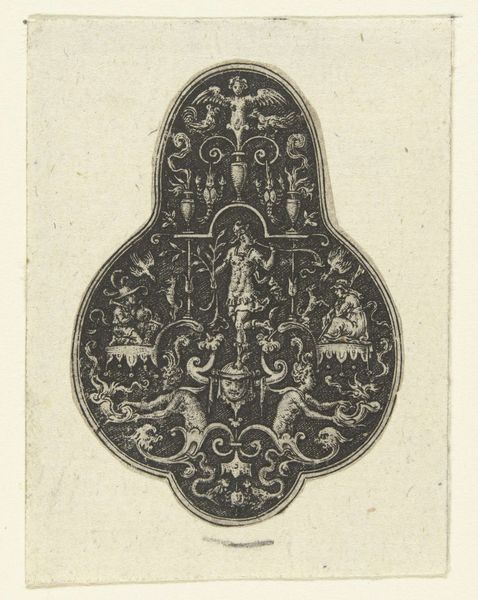

print, engraving

#

portrait

# print

#

figuration

#

history-painting

#

italian-renaissance

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 221 mm, width 105 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Editor: This engraving, titled "Spiegel: ovaal met een voorstelling van de dood van Julia" by Etienne Delaune, dates back to 1561. It's fascinating how the artist depicts such a tragic scene—the death of Julia—within what appears to be a decorative mirror. What do you think about the juxtaposition of such different elements? Curator: It is certainly a curious blending. This work’s place within social and cultural history reveals much. In the 16th century, even items of personal adornment often carried moral or political weight. Death, while morbid to our sensibilities, was a commonplace and very public aspect of Renaissance life. How does the shape itself contribute to its reception? Editor: Well, the oval shape softens the severity a little, maybe? It's less confrontational than a sharp rectangle might be. Curator: Precisely. An oval, like a mirror itself, is about reflection – both literal and metaphorical. In this context, considering the politics of imagery, how does it change our reading to imagine this death scene being reflected back at the owner? Does it seem didactic, ornamental, devotional, or something else? Editor: I suppose it encourages reflection on mortality, but also… almost luxuriates in the drama of it? Like, look at this tragic death, but also admire this beautiful object depicting it. Curator: That’s astute. Renaissance society often used art to mediate complex feelings about death. Think of the rise of elaborate tombs, funded by wealthy families; it was simultaneously grieving and memorializing whilst exhibiting social status. Could this mirror be similarly viewed as a marker of wealth and taste, as well as a somber memento mori? Editor: So, it’s about public performance of grief, not just private contemplation. I hadn’t considered that aspect. Curator: Exactly! Considering this piece helps us understand how deeply embedded visual and material culture were in shaping societal values during the Italian Renaissance. Editor: It’s a pretty morbid concept. This was definitely a deep dive into how history shapes what we see, thanks!

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.