daguerreotype, paper, photography

#

16_19th-century

#

landscape

#

daguerreotype

#

paper

#

photography

#

france

#

cityscape

#

realism

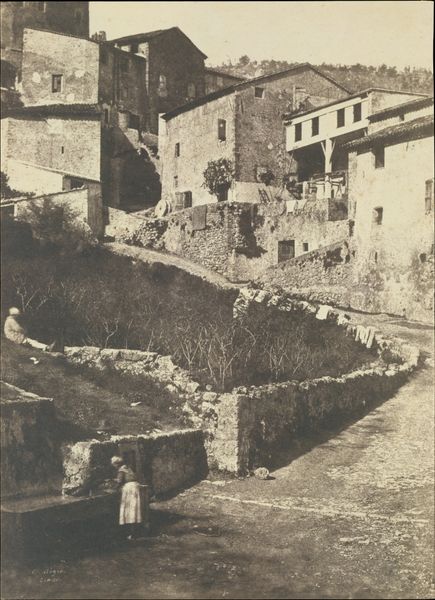

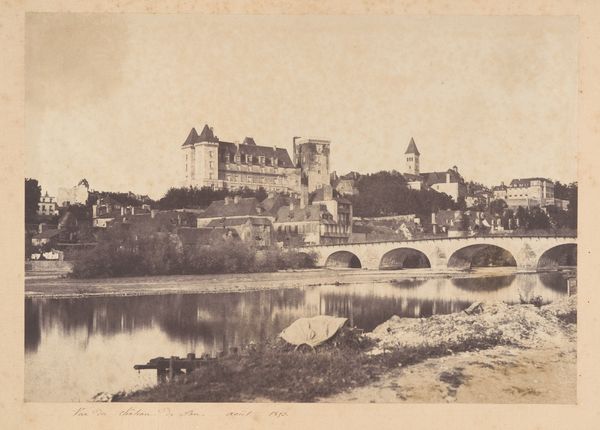

Dimensions: 15.4 × 21.2 cm (image/paper)

Copyright: Public Domain

Curator: Standing before us is "Grasse," a captivating daguerreotype printed on paper, crafted in 1855 by Charles Nègre. It's currently housed here at The Art Institute of Chicago. Editor: It’s remarkably still, almost like a memory struggling to solidify. The monochromatic tones lend a hazy feel. Curator: Exactly. Let's consider this image in the context of 19th-century France. The rise of photography wasn't simply a technological advancement. It mirrored and fueled broader societal shifts, disrupting established notions of representation and power. What did it mean to document a provincial town like Grasse in this way? Editor: I see the photographic gaze itself as a complex issue. The power dynamic inherent in image-making always needs questioning: Who is represented, and how are they represented? Why Grasse? Was Nègre interested in preserving a certain vision of rural life amidst burgeoning industrialization? It hints at complicated politics of representation. Curator: I agree entirely. And it’s important to note that while photography purported to offer objective truth, its relationship to realism was far from straightforward. Look at the placement of the figures on the bridge – almost a staging. And what's missing is crucial: any evidence of marginalized communities or labor that supported the town. This 'realism' had its limits, didn’t it? Editor: Certainly. There's also the medium of daguerreotype. These early photographs, uniquely unreproducible, created almost a relic. It wasn't merely capturing a moment, but embalming it. Curator: Indeed. These images, while appearing quaint now, served to reinforce social and cultural values. They present us with a narrative – constructed as much as captured. And even with our understanding of that history, this image has charm. Editor: Yes, it holds an odd power – both beautiful and loaded with untold stories and complex societal dynamics that the photographic lens can't fully reveal, though they can try. Curator: It’s an image, really, that benefits from considering how the past shaped its creation and our present perception. Editor: A perfect example of how viewing art becomes an exercise in layering context and interpretation.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.