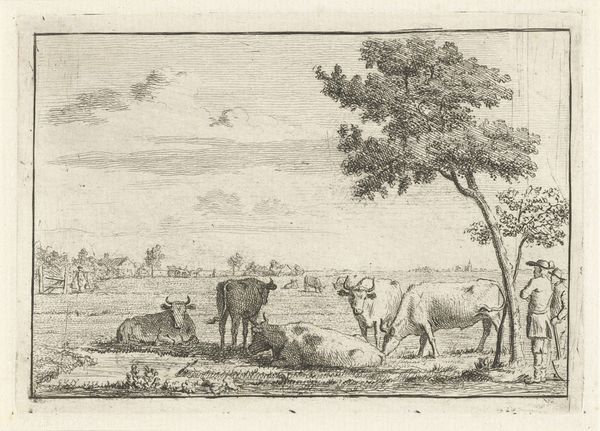

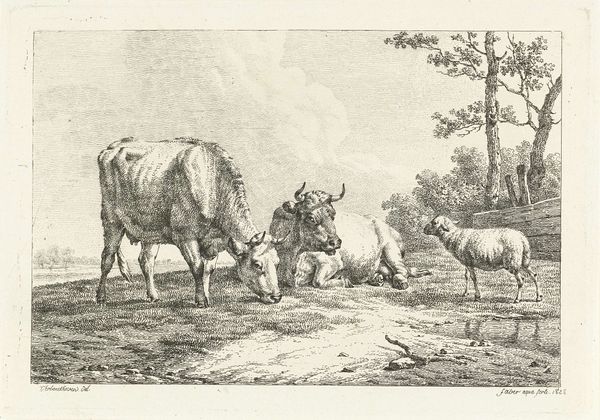

drawing, ink, pen

#

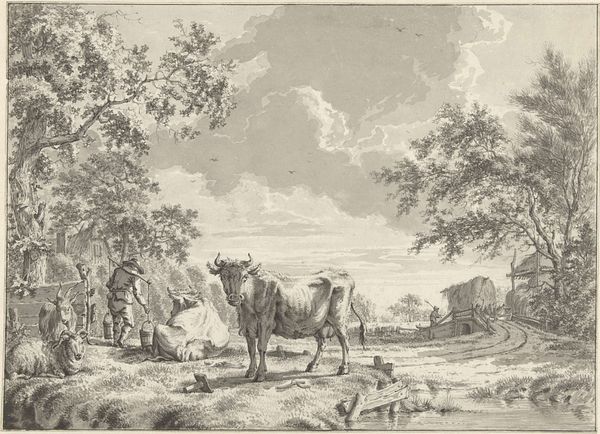

drawing

#

pen sketch

#

pencil sketch

#

landscape

#

ink

#

romanticism

#

pen

#

genre-painting

#

realism

Dimensions: height 143 mm, width 201 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: Look at this evocative pastoral scene. This is "Boerenstel in weiland," a pen and ink drawing by Frédéric Thédore Faber, created around 1831. It's currently held here at the Rijksmuseum. Editor: It has a serene, almost idealized quality. The etched lines create a tangible texture, even at this distance. I find the contrast between the meticulously drawn animals and the softer background very compelling. Curator: Considering the social landscape of the time, it’s difficult to see it as idealized without critical engagement. This was a period of stark social disparities. Do you think that representations of rural life were deployed as a deliberate distraction from urban unrest, presenting an inaccurate representation of labor and life for rural communities? Editor: That’s a strong claim and one worth digging into more, especially when you analyze the labor implied, or more specifically, glossed over, within this sort of Romantic piece. The tools these laborers use, the clothes they're wearing, how they actually churned the butter...the method and materiality of those efforts have all been conspicuously omitted. We see consumption and a product, yes, but at the great cost of ignoring all working class struggle and, well, work. Curator: Precisely. And look at the figure churning butter—gendered labor is definitely at play here. Faber isn’t simply presenting a landscape. He is presenting a particular narrative about labor roles and a family unit, filtered through the lens of artistic and societal expectation. Also, who is the intended audience for work such as this? Editor: That's crucial—it’s most likely someone wholly detached from the depicted lifestyle! Knowing it's ink on paper makes it feel very intimate, almost like looking through someone’s private journal. I wonder where the ink came from? Was it locally sourced? These may feel like pedantic concerns, but asking questions of origins makes Faber's labor as a craftsman stand out even further when the agricultural processes within the frame are ignored. Curator: By highlighting these missing contexts, it urges us to really analyze not just the "what" of art, but the "how" and the "why," which uncovers the artist’s role in either challenging or reinforcing dominant ideologies. Editor: Absolutely. Faber, in using these readily accessible materials, inadvertently emphasizes his distance from the realities of manual labor, inviting us to question these aesthetic choices. Curator: Engaging with the historical context reframes what may initially appear as a simple, idyllic portrayal, transforming it into an object ripe for critical engagement regarding social class, labor, and even early constructions of national identity. Editor: This definitely highlights the value in tracing an object’s materiality, which prompts these vital critical reflections on societal representation.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.