oil-paint, sculpture, oil-on-canvas

#

portrait

#

baroque

#

portrait image

#

portrait

#

oil-paint

#

sculpture

#

chiaroscuro

#

history-painting

#

academic-art

#

oil-on-canvas

Dimensions: 50 × 40 in. (127 × 101.6 cm)

Copyright: Public Domain

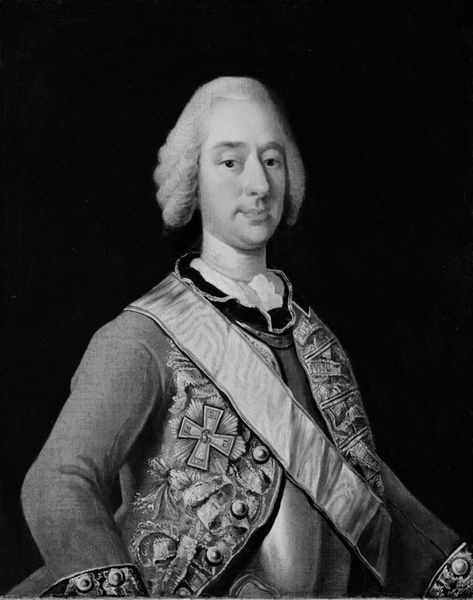

Editor: Here we have Thomas Hudson’s "John Newton," dating from around 1757 to 1760, an oil on canvas portrait. The figure is so self-assured; almost nonchalant in his pose. What’s your take on this painting, considering its historical context? Curator: Well, seeing this, I’m immediately drawn to how the painting functions as a statement of power. Consider the portrait's creation against the backdrop of 18th-century British society. The patronage of portraiture was a privilege, largely reserved for the aristocracy or those climbing the social ladder. Think about who John Newton was, or wanted to be, in relation to who this portrait was for. Editor: So, the very act of commissioning a portrait like this spoke volumes. Curator: Exactly! And look closer at the details: the quality of his clothing, the sword peeking out from behind his coat. It's not just about physical likeness; it's about projecting a particular image, legitimizing a position. These weren’t merely personal mementos but rather public declarations, reinforcing social hierarchies. How does knowing that impact how you view the work? Editor: It makes me wonder what aspects of his identity he most wanted to emphasize and broadcast to society. Did all commissioned portraits serve this purpose during this period? Curator: Generally, yes, but the nuances depended on the individual and the artist. This Baroque-era piece clearly signals status, but artists could also subtly critique those same structures. It is this delicate tension, I think, which keeps us engaged with these works. Editor: That’s fascinating. I now see beyond just the aesthetic, realizing the potent role art played in shaping social narratives of that time. Curator: And that understanding shapes how we view it today. A seemingly simple portrait reveals a complex dance of power, ambition, and representation.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.