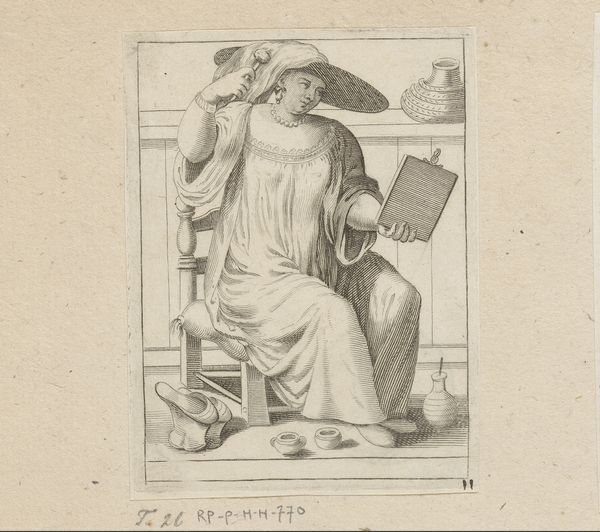

print, engraving

#

portrait

# print

#

old engraving style

#

mannerism

#

figuration

#

history-painting

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 78 mm, width 80 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: What a fascinating print. This is "Straf", created sometime between 1533 and 1567 by Enea Vico, an Italian artist working in the Mannerist style. The Rijksmuseum holds this engraving. Editor: Immediately, I'm struck by the figure's intensity and the composition's austerity. There’s something deeply unsettling about the woman's stern gaze and raised finger. What is going on here? Curator: Vico often worked with historical and allegorical themes. This image seems to depict a severe matron figure, possibly representing a kind of domestic justice or moral correction. Editor: I notice the child peering from behind the wooden structure. Is that meant to soften the visual narrative or to add an element of forbidden mischievousness to the atmosphere? Curator: Likely the latter. Prints like this circulated widely, carrying potent cultural messages. This stern woman embodies an established social hierarchy, parental authority perhaps. Think about the context –the Reformation, religious reforms challenging existing power structures. Imagery becomes a key tool. Editor: So the print would've been read, in part, through that religious and social turbulence. Does the Latin inscription, "Quos amo maternis castigans vrgeo flagris" provide an additional angle to analyze? Curator: Precisely. Loosely translated, it states "Those whom I love, I urge on with motherly chastisement and scourges". Editor: It re-frames the apparent harshness; she disciplines from a place of love. But I cannot help but feel it also normalizes potential forms of violence as positive tools, perpetuating harmful gendered roles. The threat of the whip amplifies that troubling undercurrent. Curator: An excellent observation. Considering the original viewership allows a better comprehension. Even today, though, there's no single “correct” way to interpret “Straf”, nor to assume Enea Vico’s mindset. Editor: Agreed, we must critically assess what meanings these artworks take in the contemporary moment as we reckon with our understanding of both public and private roles, punishment, and love. Curator: And now with greater access, due to public museums that enable viewers and historical artworks, they can still foster meaningful conversations. Editor: Precisely; to reconsider ingrained concepts from various points of view and to challenge norms that shape identities today.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.