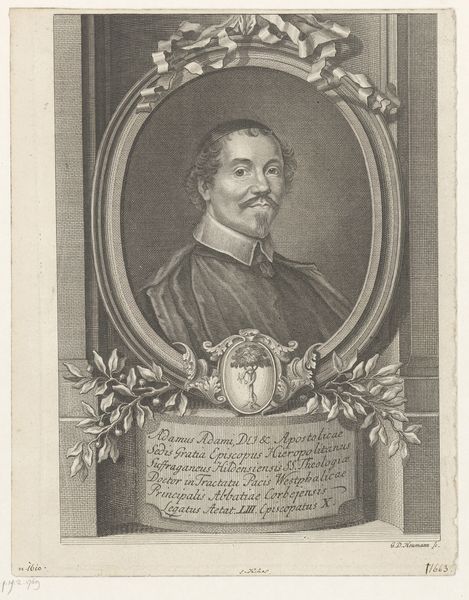

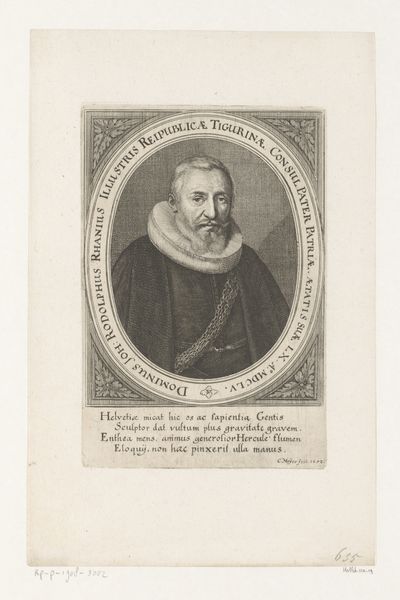

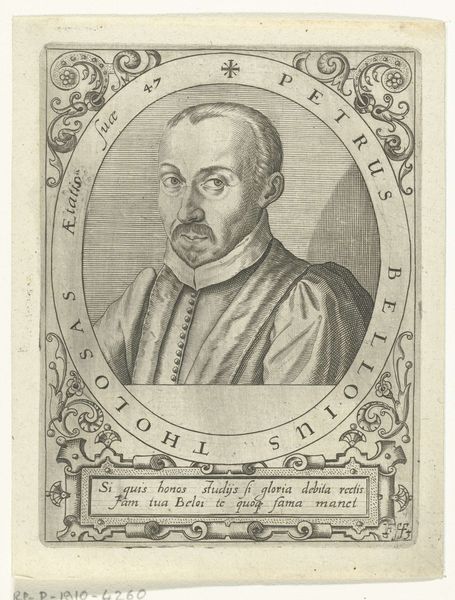

print, engraving

#

portrait

#

baroque

# print

#

old engraving style

#

portrait reference

#

portrait drawing

#

history-painting

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 205 mm, width 133 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: Immediately striking is the gravity, the formality of this figure staring back at us from a bygone era. The stark contrasts create a compelling presence. Editor: Indeed. This is a print, specifically an engraving, titled "Portret van Henri Cauchon de Maupas." It was created in 1654 by Jean Frosne. Contextualizing it, these sorts of prints played a crucial role in disseminating images of power and influence across 17th century Europe. Curator: Absolutely. Prints such as these solidified social hierarchies and religious power, specifically by focusing on key attributes like clothing. We can read the Bishop's vestments as the signifier of power and knowledge—clothing which reinforces these social and political categories. Do you agree? Editor: I concur entirely. Looking at Maupas's attire, his clerical garb immediately positions him within the Catholic hierarchy. And, the cross that hangs from his neck and coat of arms all act as visual cues denoting his high status. These are all things Frosne intentionally depicts. Curator: Right, this wasn't just an innocent attempt at portraiture but was carefully curated—in ways not dissimilar from today's social media portrayals—to control a very specific public image, an ideology. Editor: Exactly. The controlled, almost stern expression he presents enhances the sense of authority, the engraving reinforces the prevailing Baroque era's desire to evoke emotional and intellectual engagement within a religiously-inclined audience. Curator: The way light and shadow sculpt his face, that dramatic contrast… it's all so deliberate in emphasizing control and influence. The portrait becomes less about the individual and more about representing institution power, isn’t it? Editor: I agree with your assessment entirely. Jean Frosne used the artistic techniques of the time to subtly reinforce Maupas' status. He created a powerful visual statement about the intersection of personal identity and religious office in seventeenth-century France. These prints, because of their accessibility, shaped public perceptions about power. Curator: It reminds us that portraiture is rarely passive. There are underlying agendas, even in these seemingly formal depictions, it demands we engage critically with it. Editor: Very true. Considering this engraving, allows us to investigate image-making within societal structures during that period. It highlights how cultural representation of social standing shapes society’s perception, then, as now.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.