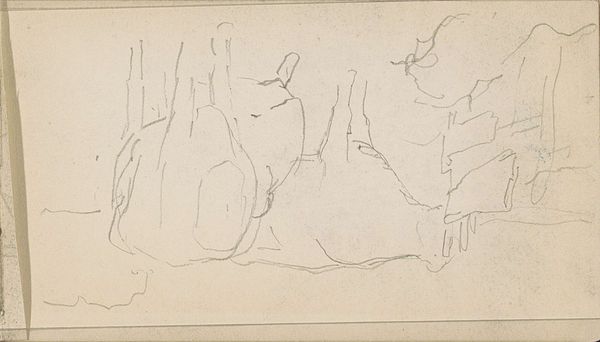

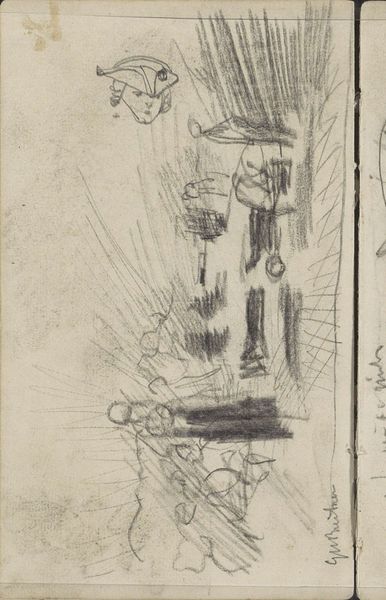

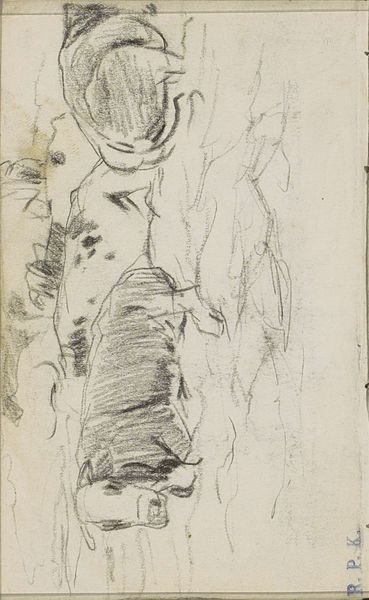

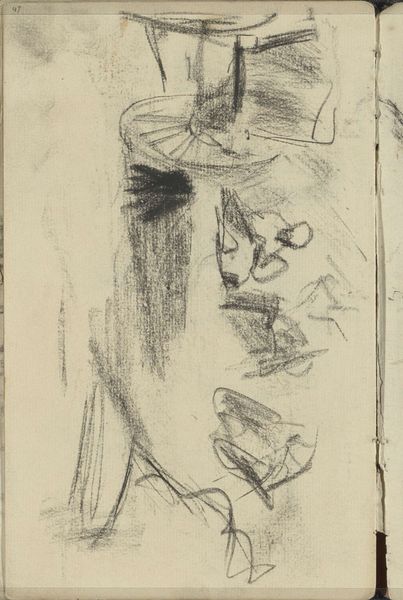

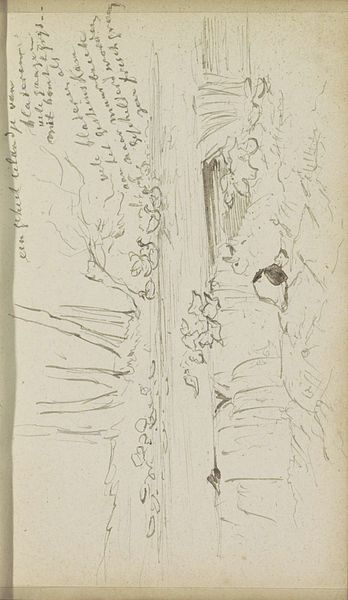

drawing, pencil

#

drawing

#

landscape

#

pencil

#

realism

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

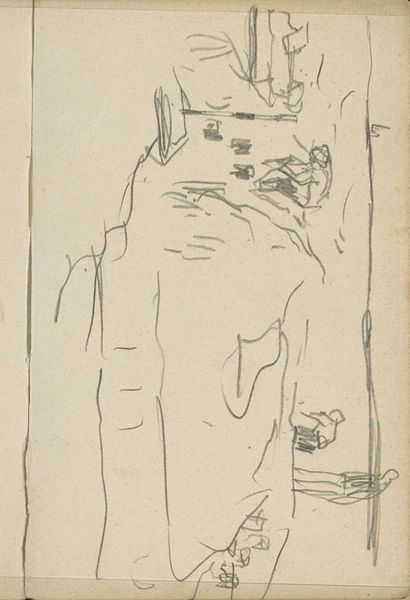

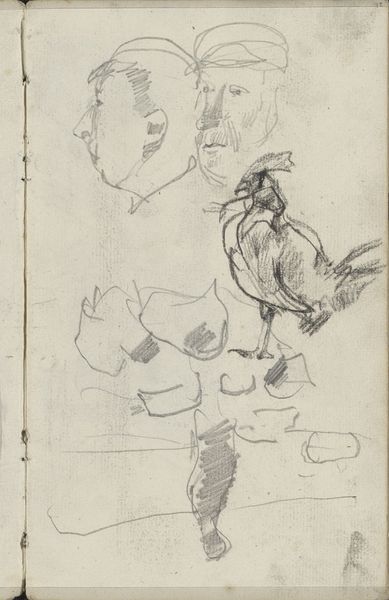

Curator: We are standing before "Cows in a Meadow by a Waterside," a pencil drawing by Anton Mauve, created sometime between 1848 and 1888. It's currently housed here at the Rijksmuseum. Editor: Immediately, I notice the almost ghostly quality. The thin pencil strokes give the composition an ephemeral feeling, like these cows might simply fade away if we look too closely. There is something haunting about such an ordinary scene. Curator: Interesting. From a materialist perspective, consider the humble pencil, a readily available tool even then. Mauve elevates this common medium to depict rural labor and the agricultural landscape that underpinned Dutch society. Editor: Absolutely. And what kind of labor is represented? These cows, subjects within a rural economy, quietly sustain an agricultural system often at their own expense. The lack of detail, however, keeps the social commentary somewhat muted, doesn't it? It's hard to read a clear politic beyond the serene depiction of pastoral life. Curator: I'm drawn to the repeated motif. Four depictions of the same subject spread across the frame. Think about it, in this period we're seeing nascent assembly-line work and increased rates of production throughout industrial Europe and the image, here, evokes repetitive and often exploitative practices, right? Editor: That's a compelling reading! It reframes the idyllic landscape within a harsher reality. Viewing these seemingly placid images as markers of labor conditions prompts an entirely different interpretation. And, further, there is labor in drawing itself--the means of production in visual form. It brings up the larger questions of art’s place within socio-economic structures. Curator: Right. While "Cows in a Meadow" doesn't overtly declare any specific agenda, a materialist lens urges us to examine the relationship between artist, artwork, subject, and the overarching network of production. What we see reflected is not a simple picture of cows, but of all the many lives—both human and non-human—sustained within agriculture. Editor: It enriches our experience and understanding when we look beneath a seeming calm and consider social implication in what might be otherwise construed as picturesque realism. The artistic process, itself, bears ethical weight. Curator: Indeed. It compels us to look at these pastoral scenes critically, revealing a depth of meaning often overlooked in more traditional analyses.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.