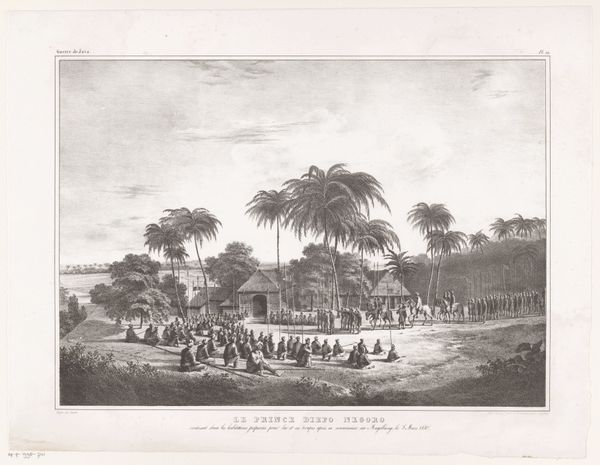

drawing, lithograph, print

#

portrait

#

drawing

#

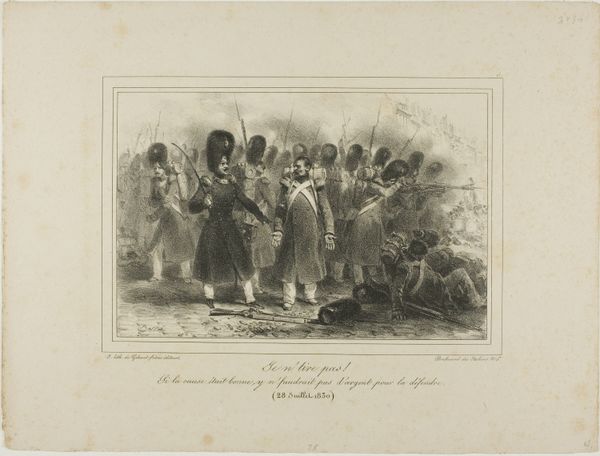

lithograph

# print

#

group-portraits

#

romanticism

#

cityscape

#

genre-painting

Dimensions: height 521 mm, width 717 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

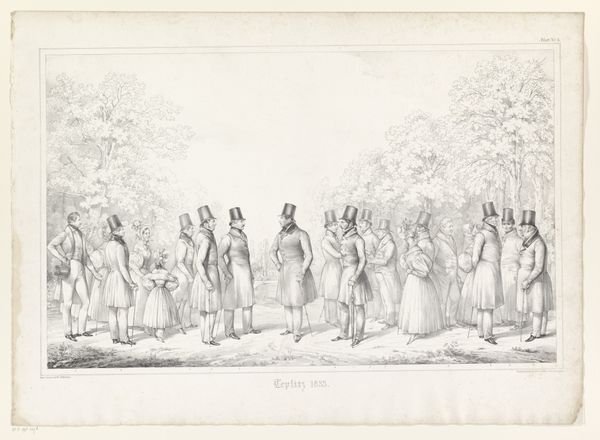

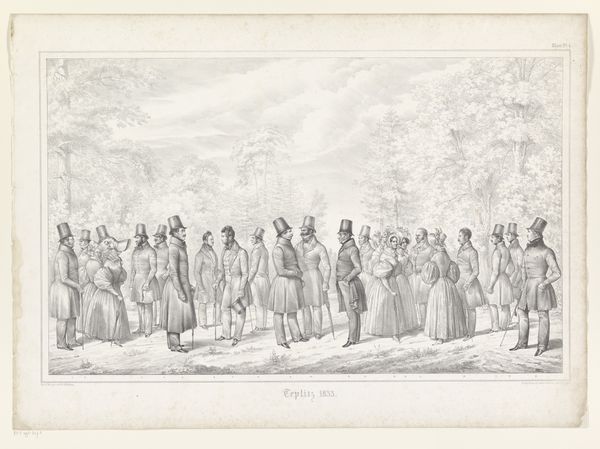

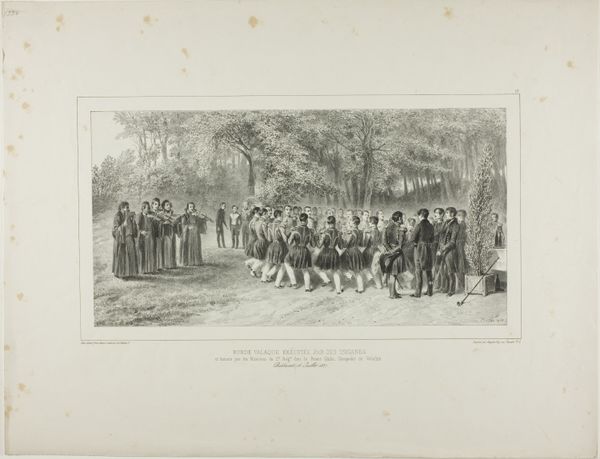

Curator: Here we have Theodor Hosemann's "Portretten van veertien personen te Teplice," created as a lithograph in 1833. What are your first impressions? Editor: It’s… remarkably stiff. Everyone is so formally posed. You almost get a sense of the social expectations and hierarchies baked into the image, almost like a yearbook photo. Curator: It's interesting you say that. Hosemann uses lithography, a printing technique, allowing for relative ease of reproduction. This lends itself to distribution, documenting the burgeoning middle class taking to spa towns like Teplice. Think about that impact on visualizing social status and shared cultural identity. Editor: Exactly! This isn't just a random gathering. It speaks volumes about who had access to leisure, to "taking the waters" – primarily the bourgeois. It’s an incredibly class-conscious image. Who is included? Who is excluded? And what narratives are they actively projecting by publicly exhibiting their affluence through leisure activity. Curator: Consider also how the materiality contributes. Lithography allows for a high level of detail. Look at the textures in the clothing, the distinct faces. This isn’t mere representation; it's a curated construction, achieved through labor. This kind of granular detail can only come with increased time spent with the stone and, presumably, the portrayed. Editor: Right, and within Romanticism we get this idealization often presented at the expense of acknowledging very real inequalities. There's this sanitized, almost nostalgic portrayal of societal gatherings. Curator: And don't discount the craft. Lithography itself demanded a particular skill set; from the initial drawing to the printing, it was labor intensive. It collapses the distinction between a painting and printed media by rendering almost painterly effect. The labor behind something we could now consider disposable speaks volumes. Editor: The piece almost acts as an anthropological document, codifying a specific historical moment. Who are these people, really? What's behind those carefully constructed appearances, beyond just documenting leisure in the rising middle class. How is social currency displayed and circulated among specific social ranks, like this depicted here? Curator: Absolutely. Examining the intersection of the hand-drawn, the mechanically reproduced, the subject matter, allows a greater critical unpacking, even with all the historical limitations to navigate. Editor: I suppose looking past just the faces and acknowledging all of the visual culture here gives it new life in examining class dynamics and image circulation, then and now.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.