Het standbeeld voor Hendrik IV wordt naar de Pont Neuf gebracht, 1818 1818 - 1839

0:00

0:00

drawing, print, etching, engraving

#

drawing

#

narrative-art

# print

#

etching

#

group-portraits

#

romanticism

#

cityscape

#

history-painting

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 477 mm, width 637 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

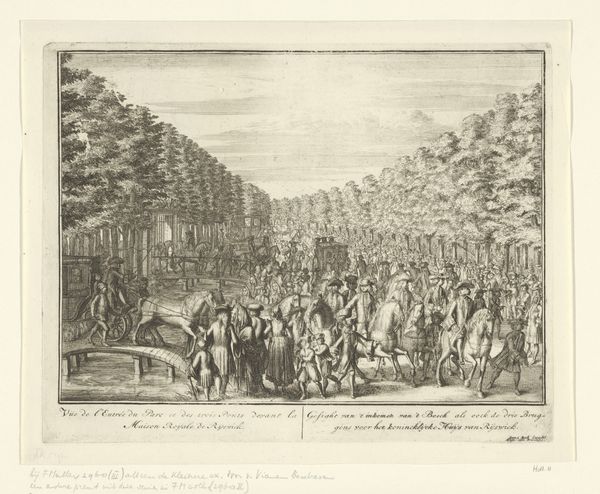

Curator: This image, realized as an etching with engraving, comes to us from Jean Henri Marlet. Titled "Het standbeeld voor Hendrik IV wordt naar de Pont Neuf gebracht, 1818," or translated, "The statue of Henry IV is brought to the Pont Neuf, 1818," it dates from between 1818 and 1839. It certainly appears a very busy, celebratory scene. Editor: It feels… chaotic, almost. There's a sense of restless energy, a frenzy of movement emphasized by the almost frantic quality of the lines. It evokes a sense of communal fervor, doesn't it? But is it genuine enthusiasm or something more…staged? Curator: Ah, excellent question! The statue of Henry IV has a history laden with political symbolism. Originally erected by Marie de Medici, it was destroyed during the Revolution. This image captures its post-Napoleonic restoration, a very deliberate act by the restored monarchy to re-establish a sense of continuity with pre-revolutionary France. Editor: So, its return was more than just remembering a beloved king. The figure of Henry IV becomes a kind of anchor to which the Bourbon monarchy can moor itself to recover legitimacy and authority? Curator: Precisely! Look closely at the figures pulling the statue. Their exertions, the sweat implied in the hurried lines—it's designed to appear as though all of France is literally pulling together to restore the past. And look at the figure of the lone man walking casually with the bow slung across his back while those men heave under great exertion, and notice that figure in full military garb astride a horse. These were staged characters playing at an important performance to inspire in their fellow Frenchmen national confidence. Editor: So, Marlet’s etching, while appearing documentary, is actually a piece of political propaganda, illustrating the regime’s narrative and making it look as if it is organic. The seemingly candid joy is meticulously manufactured for those who know the story behind the scene? I keep thinking about the nature of civic spaces: that bridge serving almost as a theater here... Curator: Absolutely. It makes you think about the many layers of meaning embedded in even seemingly simple depictions of public events. We see now that Marlet gives us a snapshot not of spontaneous joy, but the careful engineering of national identity through art and public spectacle. Editor: An important lesson: images aren't always what they seem. What seems like a candid snapshot could well be a carefully constructed stage play about the nature of cultural and political performance!

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.