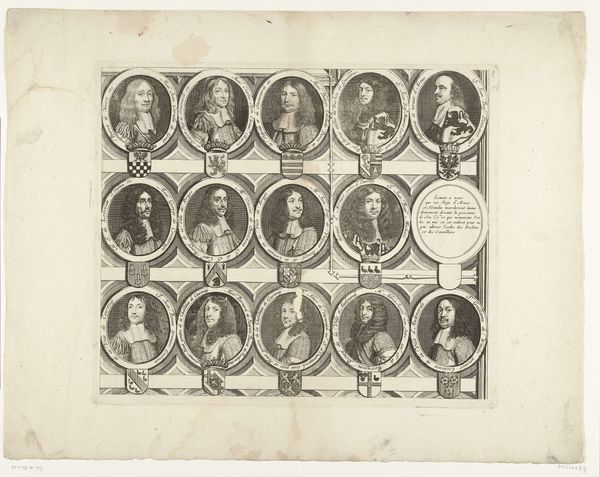

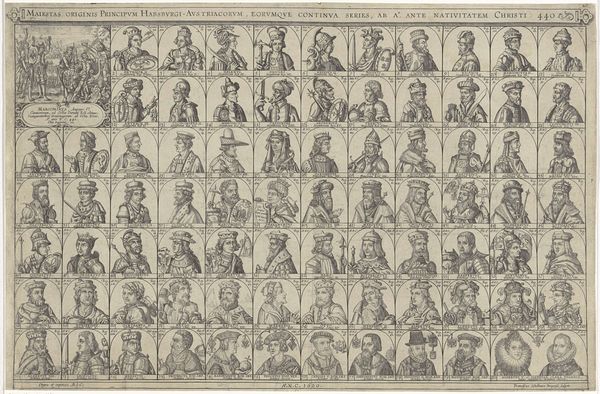

Portretten van Willem I, prins van Oranje, zijn zoons Filips Willem, Maurits en Frederik Hendrik, prinsen van Oranje, Amalia van Solms, hun zoon met echtgenote, hun dochters met echtgenoten, en een kleinkind c. 1645 - 1706

0:00

0:00

print, engraving

#

portrait

#

pen drawing

#

dutch-golden-age

# print

#

figuration

#

group-portraits

#

line

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 417 mm, width 527 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: Here we have a rather formal grouping of portraits—an engraving, to be precise, that dates from around 1645 to 1706. It's called "Portraits of William I, Prince of Orange, His Sons, and Their Families." It belongs to the collection of the Rijksmuseum. Editor: My first thought? It looks like a family tree rendered in metal! The repetitive oval frames give it a stamp-like quality, suggesting mass production and, perhaps, wide distribution. What materials were involved in the making of this print, anyway? Curator: Excellent observation. The line engraving, you see, uses a metal plate, usually copper. Lines are cut into the plate, which holds the ink when the surface is wiped clean. It is then pressed onto paper. It evokes clarity and permanence. Each member is distinct but linked by visual cues, representing the continuation of the family line and its attendant virtues. It's very Dutch Golden Age in its restraint, wouldn’t you say? Editor: Definitely. It screams efficiency, the assembly-line production of noble imagery! It makes you wonder, though, about the workshop practices of the time. How many hands touched this plate? Whose labor were we celebrating when admiring it as "art"? And the intended function--obviously promotional. I find myself much more curious about the social impact and commercial aspects than symbolic meanings here. Curator: You're not wrong. There’s that calculated element there in this lineage, but it's not *just* about surface. The print itself performs its symbolic function beautifully: a rigid structure housing representations of real power relationships and historical trajectory, all very self-aware. The composition with the different portrait frames acts as visual signifiers; connecting one generation with another and reinforcing legitimacy. Editor: That legitimacy was certainly bought and sold, printed and distributed! All that subtle suggestion about lineage actually translates into explicit economic and political power. I still circle back to thinking about how the social machine that created it might tell an even richer story. Curator: A fitting end to a compelling dialogue then, reminding us there's far more to any artwork than meets the casual eye. Editor: Indeed, and to remind everyone to go explore Rijksmuseum´s holdings whenever you can!

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.