painting, oil-paint

#

portrait

#

character portrait

#

portrait

#

painting

#

oil-paint

#

portrait subject

#

figuration

#

11_renaissance

#

male-portraits

#

portrait head and shoulder

#

edgy portrait

#

facial portrait

#

northern-renaissance

#

portrait art

#

fine art portrait

#

celebrity portrait

#

digital portrait

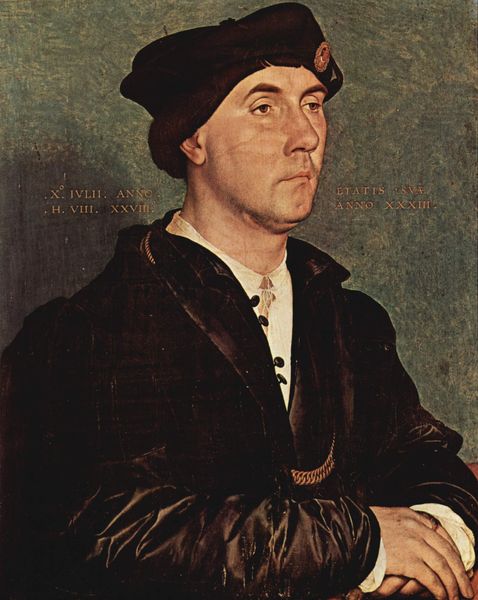

Dimensions: 81.4 x 66 cm

Copyright: Public domain

Curator: Hans Holbein the Younger painted this imposing “Portrait of Sir Henry Guildford” in 1527. The medium is oil paint. Editor: My immediate impression is one of controlled opulence, don’t you think? The dark hues of the fur contrast sharply with the shimmering gold brocade. It feels deliberately composed. Curator: Indeed, the golden sleeves and surcoat are so elaborate, suggesting Guildford’s status and power. But there's also something fragile in the details—those small red ornaments around his neck evoke religious rosary beads, while that barely visible coat of arms suggests family lineage. It hints at ancestral achievement and religious faith intertwined with earthly power. Editor: Note how Holbein plays with textures. The soft fur against the hard glint of gold creates this push and pull across the surface, leading the eye around the painting. Look at the pattern of light, and the density of detail versus the expanse of solid colour, all held in absolute compositional balance. It seems Holbein wants us to focus on surfaces and materials. Curator: But it is more than just an array of textures. The plant depicted at the backdrop resembles a grape vine, which of course connects with the Holy Eucharist – the sacrament commemorating Christ’s Last Supper. The setting then reinforces the sitter's significance within both religious and secular spheres. He’s both a man of this world and the next. Editor: I'm struck by Guildford’s inscrutable gaze. His eyes don’t quite meet ours, rendering him almost unknowable. This elusiveness adds depth to the painting. Holbein’s precision highlights this further: sharp focus reveals surface appearance rather than inner substance. It's a conscious manipulation of visual space. Curator: Exactly. And it also points to the Renaissance fascination with appearances—and with crafting a specific image to project onto the world. Guildford is presented here not just as a man but as an ideal, an emblem. The choice of specific fabrics, metals, plants -- and even the cut of his hair -- becomes a constructed presentation of virtue and influence. Editor: So Holbein gives us a masterclass in pictorial rhetoric then, rather than any simple, descriptive account of a subject’s appearance. The material details, which seemed merely beautiful on first glance, work harder, shaping a sophisticated meditation on worldly and otherworldly values. Curator: Absolutely, I see the portrait now less as an object representing the subject and more as an artefact that actively evokes a particular historical moment in time, culture and even individual thought.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.