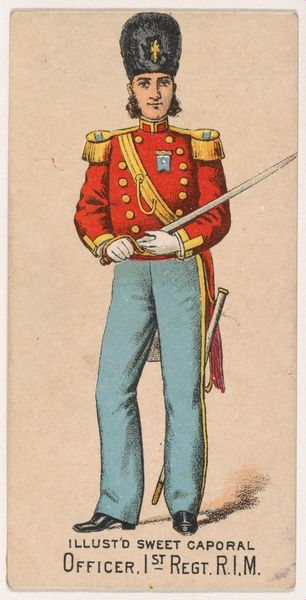

Officer, Cadet Infantry, Rhode Island, from the Military Series (N224) issued by Kinney Tobacco Company to promote Sweet Caporal Cigarettes 1888

0:00

0:00

drawing, print

#

drawing

# print

#

caricature

#

caricature

#

men

Dimensions: Sheet: 2 3/4 × 1 1/2 in. (7 × 3.8 cm)

Copyright: Public Domain

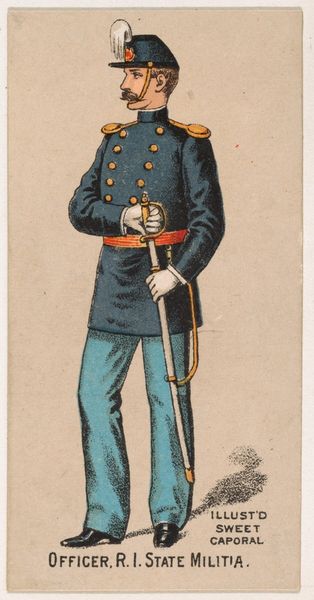

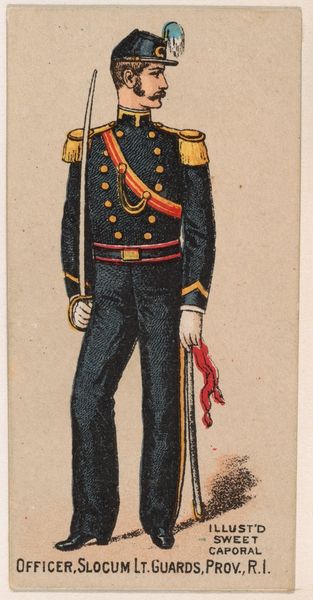

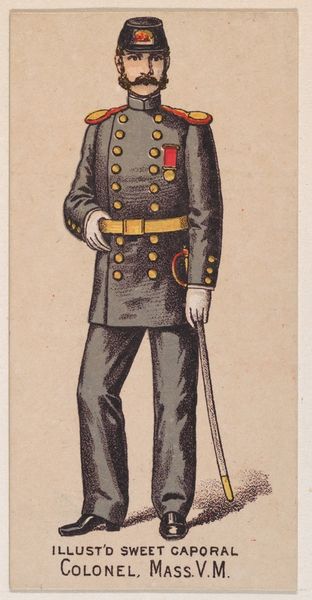

Editor: This is "Officer, Cadet Infantry, Rhode Island," a drawing and print from 1888 by the Kinney Brothers Tobacco Company. It looks like it was originally a promotional card. What strikes me is how idealized the cadet seems; what can you tell me about it? Curator: Absolutely. Focus on the print medium itself. Consider its original function: an advertisement distributed with Sweet Caporal cigarettes. It’s an intriguing example of how art becomes entangled with consumer culture and serves promotional ends. Editor: How does that affect its artistic value? Is it still "art" if it’s meant to sell cigarettes? Curator: That's the crux of it, isn’t it? Traditionally, we separate ‘high art’ from commercial art. But a materialist perspective encourages us to examine how those boundaries are blurred. Who were the artists making these images, and what were their working conditions? What materials did they use, and how did the printing process itself shape the image? Editor: I never thought about that side of it...the labor! It changes how I see the work. I’m guessing there was an entire industry making these cards. Curator: Exactly. This seemingly simple image connects to a larger web of production, distribution, and consumption. Consider also how it romanticizes military service during a period of industrial growth and shifting social values. It offers a glimpse into the values of the era and how those values were commodified. Editor: So, it’s more than just a portrait. It's about the whole system of how it was made, circulated, and what it represents. Curator: Precisely. Thinking about those processes unlocks a richer understanding than simply judging its aesthetic appeal. It’s a lens into late 19th-century American culture, connecting material objects with economic and social structures. Editor: I will definitely remember to consider the material context in all the artwork that I study in the future. Curator: Fantastic. That’s the key takeaway here today, and will unlock entirely new approaches to understanding art history.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.