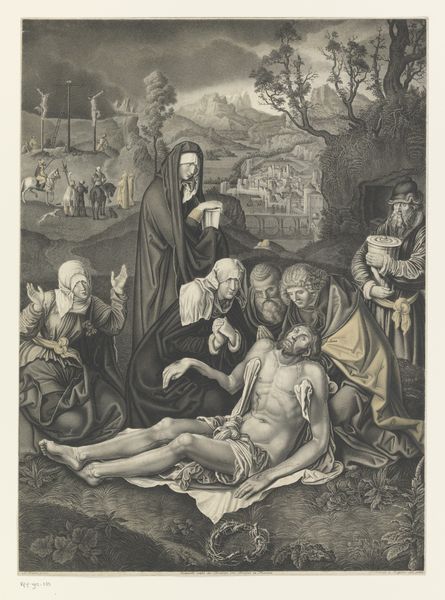

print, engraving

#

allegory

#

baroque

# print

#

figuration

#

history-painting

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 305 mm, width 232 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: Let's consider this print, "Heiligen Sebastiaan, Rochus, Maria en Blasius," made around 1630 by Giovanni Battista Pasqualini. It's an engraving, offering a rich tapestry of religious figures. What strikes you initially? Editor: A somberness, definitely. The wounded Saint Sebastian immediately pulls focus. There's an undeniable vulnerability in his pose that makes me think about societal perceptions of the body, and how even in religious art, ideas about pain and submission are frequently framed by and reinforced through masculinity and gender. Curator: Absolutely. The image unfolds within a tumultuous period of religious and social change. Saint Sebastian, riddled with arrows, anchors the scene on the lower left, acting almost as a point of suffering within a devotional appeal against the plague, along with the presence of Saint Roch. Editor: It's hard not to think about that appeal within the framework of power dynamics. Who is given voice, whose suffering is considered worthy of immortalizing in art? Is it a commentary on collective grief or does it glorify martyrdom to control discourse around disease and death? Curator: It's both. It's certainly about seeking divine intervention against the plague, and it visualizes an intricate theological hierarchy, but there's no simple way of interpreting this artwork as Pasqualini draws upon baroque elements, known for its intricate details and use of contrasts. He has included God the Father, holding the T-cross, which suggests redemption. And above Saint Sebastian, we have a contemplative Virgin Mary in the upper-left corner, offering solace and divine comfort, as Saint Blaise occupies the right corner looking on, suggesting their protective oversight. Editor: Thinking of that era, plague outbreaks brought existing social inequalities to a critical breaking point. Art, at the time, could serve as both propaganda and a reflection of public anxieties. So, is this image empowering to a suffering community or perhaps more accurately an affirmation of a religious stronghold amidst societal terror? Curator: Precisely. Art of this era becomes inextricably linked with power, persuasion, and control of imagery. These artists are very rarely unbiased storytellers and truth-seekers. Editor: The question is still very potent now: who narrates, who is heard, and how those portrayals sway shared narratives? Curator: Indeed. I believe thinking through the layers of history alongside more contemporary theoretical perspectives allows a richer interpretation.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.