#

narrative-art

# print

#

asian-art

#

ukiyo-e

#

figuration

Dimensions: height 116 mm, width 135 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

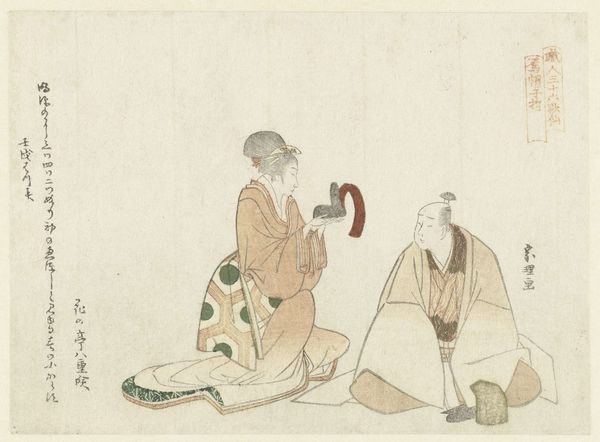

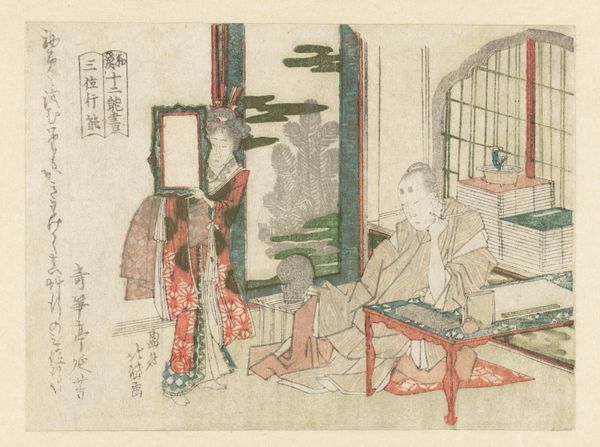

Editor: So, this is "Egoyomi voor het jaar van de haan," a print made around 1789. I'm immediately struck by the figures – they appear to be anthropomorphic animals. What's your take? What is this saying? Curator: Well, seeing anthropomorphic animals in ukiyo-e prints isn't necessarily unusual; such pieces often served social and political purposes. "Egoyomi" were calendar prints, and in 1789 it was the year of the rooster. The rooster figure, and the fact that both it and its interlocutor are contemplating calendars, satirizes contemporary societal trends in late 18th century Japan. Consider the visual language—the subdued colors, the enclosed interior setting—they lend a contemplative air, almost a critique. Editor: A critique of what, specifically? Curator: Likely the restrictive policies of the Kansei Reforms. This legislation tried to reinforce Neo-Confucian morality and social order. The humorous animal figures in traditional garments could serve as a commentary on how those policies were seen. They offered veiled criticisms that resonated with an audience weary of political rigidity. Do you think the placement of the open window alters your impression of the interior scene? Editor: It suggests an outside world, one potentially more free. Is it subversive because of the political restrictions, or just the humourous imagery? Curator: It's both. The imagery operates as a form of protest, a clever way to communicate dissent under a watchful eye. It's art embedded in social commentary. Editor: That’s fascinating! I never thought about calendar prints being tools for social commentary. Curator: Exactly! Looking deeper reveals art's power to mirror and mold society.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.