photography, glass

#

photography

#

glass

#

macro shot

#

united-states

#

macro photography

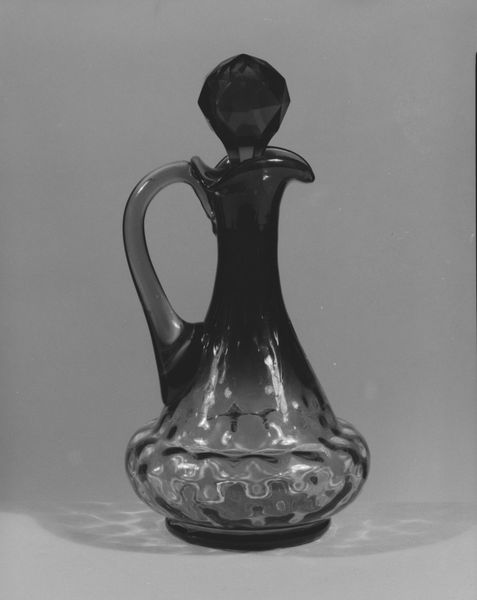

Dimensions: H. 6 1/2 in. (16.5 cm)

Copyright: Public Domain

Editor: Here we have a photograph of a glass cruet made by Adams and Company sometime between 1870 and 1890. It has these incredible textures—bubbles, ridges, a scalloped rim. The composition, with the cruet isolated against a blank background, almost turns it into a portrait. What stands out to you? Curator: Immediately, I think about domesticity and labor. Objects like this cruet weren't simply decorative; they were tools within a specific socio-economic structure. Who owned this cruet? Who cleaned it? Was it a symbol of status? Considering the late 19th century, these questions open up discussions around class, gender roles, and the exploitation inherent in maintaining a certain lifestyle. Editor: I never thought about it like that, I was just looking at it formally. The texture almost obscures the object... Curator: Exactly. Think about the "hobnail" pattern: it imitates cut glass, but at a lower cost, democratizing luxury. However, this accessibility hides the reality of the factory workers, often women and children, whose labor made such imitation possible. Do you see how the cruet, seemingly innocent, becomes entangled in a web of social and economic inequalities? Editor: That’s a very different interpretation than just admiring it for its aesthetic qualities. Is it wrong to find beauty in it, knowing the context? Curator: Not at all. It is vital to reconcile its formal beauty with the context. Art doesn’t exist in a vacuum. Recognizing these tensions allows for a more nuanced and critical appreciation. We acknowledge beauty but resist romanticizing the history. Editor: So by acknowledging both, we get a fuller picture. Thanks! Curator: Precisely. Examining the social implications transforms how we perceive even the simplest objects.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.