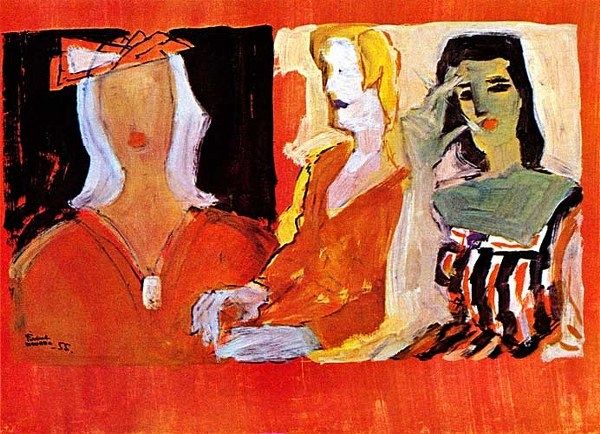

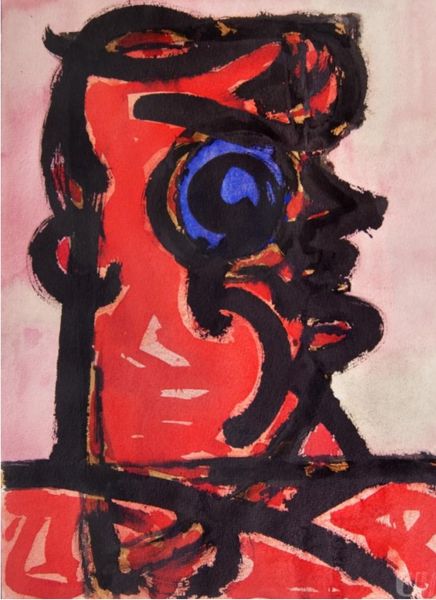

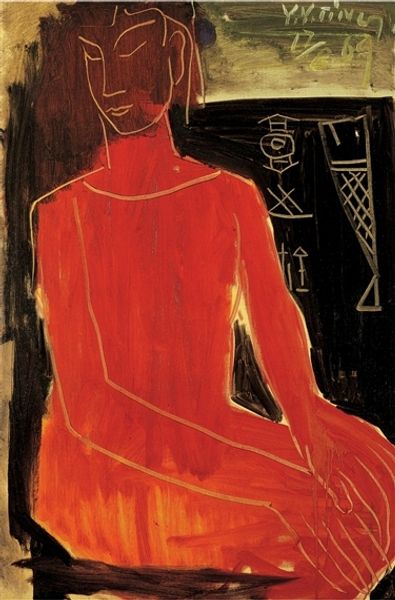

Copyright: Houria Niati,Fair Use

Curator: Let’s pause here in front of Houria Niati's searing "No To Torture," painted in 1982, done with oils. A visceral reaction is pretty unavoidable, wouldn't you say? Editor: Absolutely. It's…bruising. The stark, almost clashing colours, those trapped figures. There's a raw vulnerability, but also an undeniable rage simmering beneath the surface. It feels immediate, like a primal scream captured on canvas. Curator: Exactly. Niati was exploring the harrowing realities of political imprisonment and torture. She doesn't shy away from depicting the body as a site of suffering. Notice how each figure seems contained, isolated, even those boxy forms around their heads suggest something is closing in. Editor: Yes, that's fascinating. Those boxy, almost cage-like red forms – they remind me of the distorted perspective we sometimes see in depictions of hell or purgatory in older religious iconography. And the absence of clear facial features… it dehumanizes them, making them almost archetypal victims. Curator: I read the red boxes to be branding each figure, like torture turns individuals into products of injustice. She makes you feel the claustrophobia, the suffocation, even without explicitly showing acts of violence. I think it leaves more to our own imaginations that way. Editor: The colours, too, have a weight. The blue, traditionally associated with serenity or even divinity, here feels cold and oppressive. The jolting orange of one of the figures is painful, and jarring. Nothing's resolved, is it? Even that grounding red that anchors it gives me a bad vibe. Curator: No, nothing is resolved. I find her brushwork frantic, each stroke a deliberate mark of resistance, perhaps? Considering it’s ’82 it fits well with the other art styles coming into focus at the time. I almost think she paints freedom, paints her refusal. Editor: And, perhaps, it also becomes a question of who "we" are in the face of such realities. Who are we to view such pain from a safe distance? Niati compels us to confront our own complicity and indifference. And what the price to remain neutral may mean. Curator: Indeed. There's a universality here that transcends specific political contexts, too. Niati reminds us of the persistent human capacity for cruelty. That makes the work remain tragically relevant, no? Editor: Sadly, yes. It’s an enduring cry against injustice, a refusal to let such horrors be forgotten. You almost wish, when passing art such as this, to do some immediate good with that fiery awareness it evokes in you.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.