photography, photomontage

#

muted colour palette

#

landscape

#

photography

#

photomontage

#

orientalism

#

muted colour

#

genre-painting

#

natural palette

Dimensions: height 138 mm, width 200 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

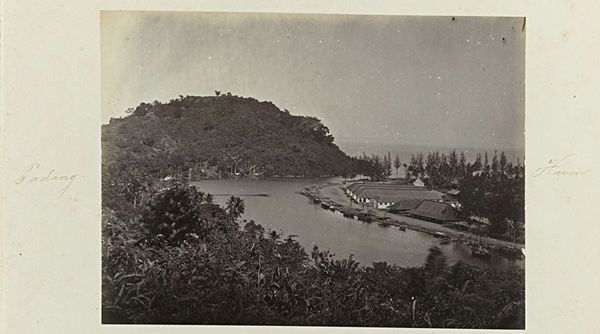

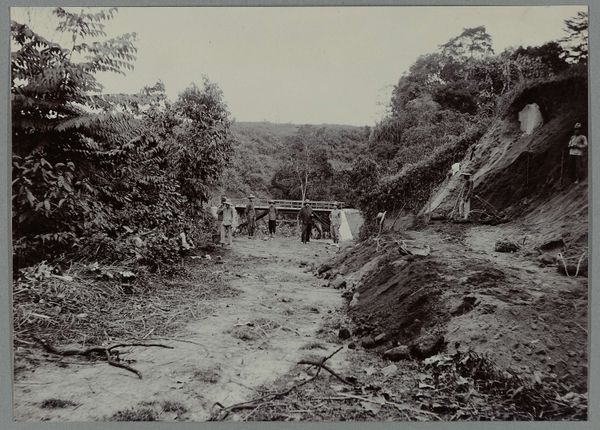

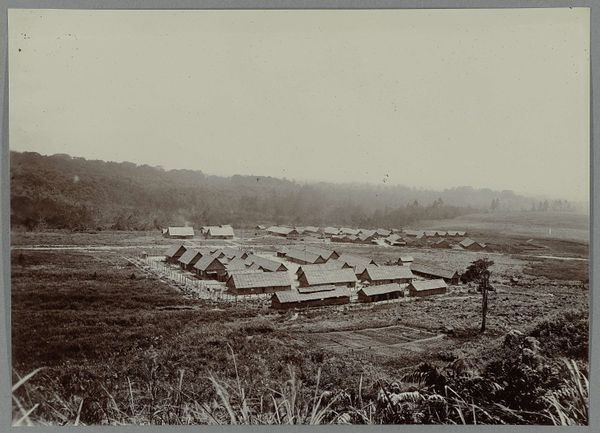

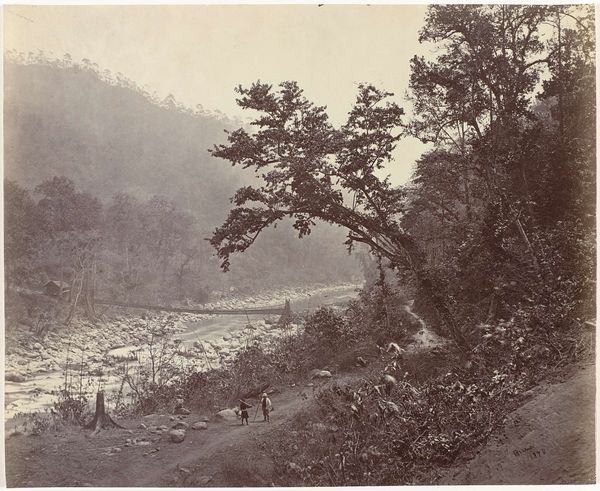

Editor: This is an intriguing photomontage, *Bivak te Krueng Seumpo*, created sometime between 1903 and 1913. It depicts a village scene nestled within a dense, mountainous landscape. I’m struck by its slightly unsettling calm; there's a sense of detachment. How do you read this image, especially given the period it was created? Curator: The "calm" you perceive might be the very ideological strategy at play. This image presents itself as a neutral observation, but we need to consider its production within the context of Dutch colonialism in the Aceh region. Images like these often served to document and, in a sense, legitimize colonial power. What do you think about the perspective used? Is it from inside the community or from a distant position? Editor: It definitely feels distant, almost voyeuristic. Like we’re positioned outside, observing rather than participating. Does that relate to the concept of "Orientalism"? Curator: Precisely. "Orientalism", as defined by Edward Said, suggests a way of seeing that emphasizes, exaggerates, and distorts differences of Arab peoples and cultures in comparison to those of Europe and the U.S.. The artist's Western gaze creates an "us" versus "them" dynamic, reinforcing stereotypes of a distant, exotic "other" requiring external governance and control. Look at the framing, the way the image is composed. Is it about understanding, or about control? Editor: Now that you point it out, the composition emphasizes order and control— the neat rows of buildings, the structured pathways. It’s less about depicting a lived reality and more about showcasing a pacified territory. I hadn't considered that before. Curator: These seemingly objective images played a significant role in shaping public perceptions and justifying colonial policies. It’s essential to critically analyze these visual representations and understand the power dynamics embedded within them. Considering contemporary discourses around representation and decolonization, what are the ethical responsibilities of institutions displaying such works today? Editor: I think that context is crucial. Simply displaying the image without acknowledging the power structures behind its creation would be a disservice. Thanks, I see this photograph with entirely new eyes now. Curator: Exactly. Engaging critically with these narratives enables a deeper understanding of historical injustices and fosters more inclusive dialogues.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.