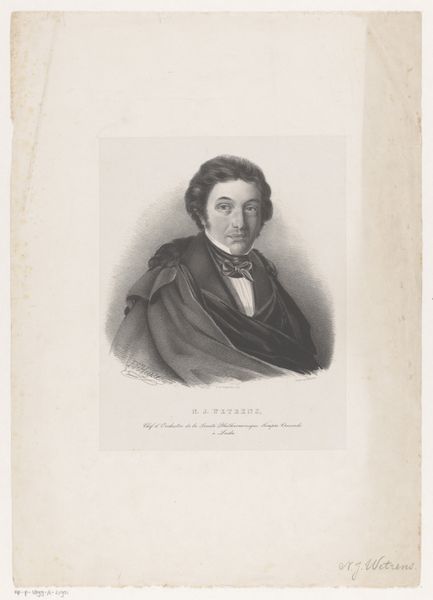

drawing, graphite

#

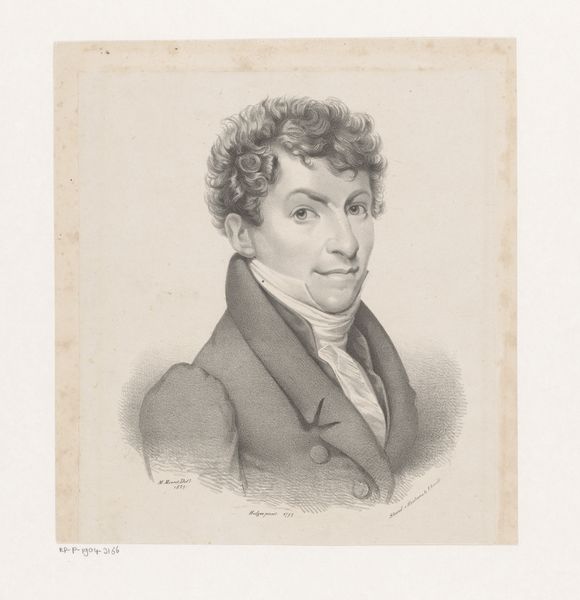

portrait

#

drawing

#

romanticism

#

graphite

#

portrait art

Dimensions: height 349 mm, width 293 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: This is a portrait drawing by Henricus Wilhelmus Couwenberg, titled "Portret van F. Mispelblom Beyer," created in 1842. Editor: The graphite lends itself to the softness of the portrait, doesn't it? It gives it a subdued and thoughtful air, a sort of quiet observation of this individual. Curator: Indeed. And beyond the mood, I'm interested in how the artwork speaks to 19th-century Dutch society. Portraits like these were often commissioned by the burgeoning middle class to solidify their social standing. Who was F. Mispelblom Beyer, and what role did he play in the era's socio-political landscape? His identity could offer a fascinating glimpse into the network of power and influence at that time. Editor: Absolutely. I agree about the solidification, and also let's not dismiss the labor that goes into these portraits, especially the process of acquiring graphite. How were graphite materials sourced and processed in 1842, and what does that reveal about the connection between artistry, industrial growth, and, you know, potentially global extraction in that era? Curator: That’s an insightful point. Considering the portrait as an object rooted in its material origins allows us to unpack the complex relationship between artistic production and the economic realities that underpinned it. We can ask questions about who benefited from this material trade. And moreover, how that era used this new way to fix likeness to control narratives about itself? Editor: Right! How did those specific tools and techniques employed shape not only the artistic representation but also our understanding of social structures? You look at his clothes, that kind of tailored piece that suggests status and material access. It represents both labor and also something desired in those emerging markets you were speaking to. Curator: I'm also thinking about the sitter’s gaze. It isn't direct, it’s contemplative and slightly averted. That combined with that carefully orchestrated, classical arrangement speaks volumes. Does this hint to something about his place within the existing, probably very restricted societal norms? Or, also to the expectations surrounding the depiction of men during that period? Editor: Yes, I suppose in considering the role of portraiture at the time we come closer to an understanding of its subject as well. It makes me think about all the unrepresented people we might have understood if these graphite materials had not been reserved only for these subjects. Thank you for giving me that to consider, I think, looking at these processes helps see into that history more fully.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.