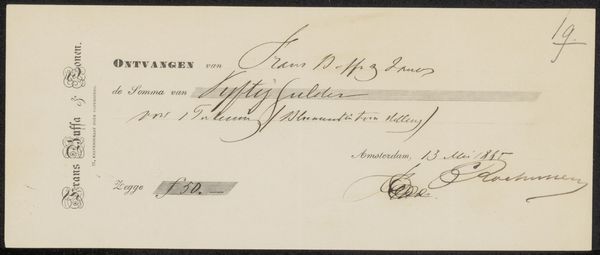

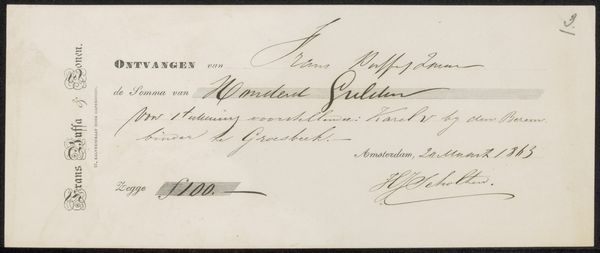

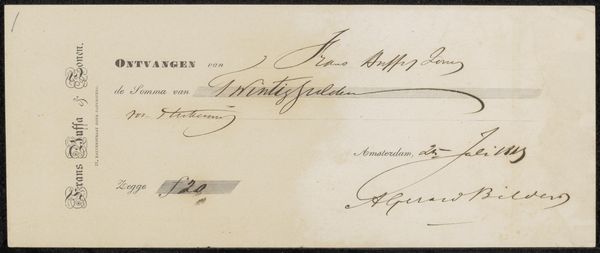

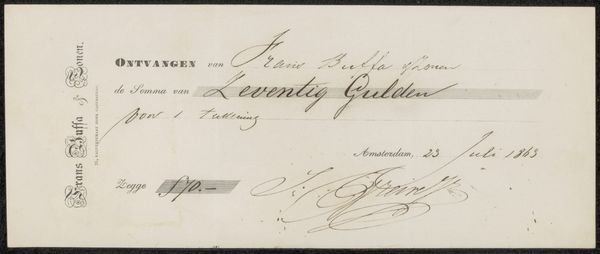

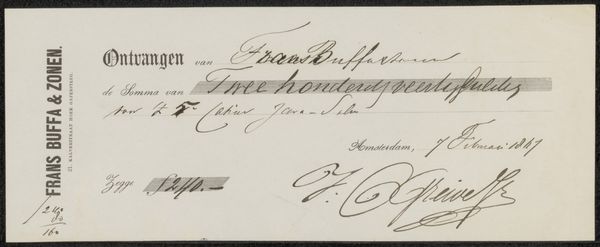

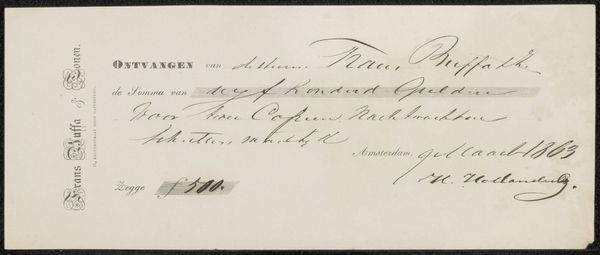

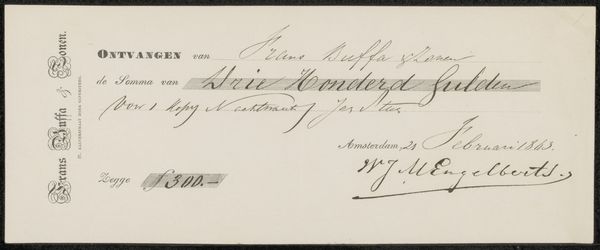

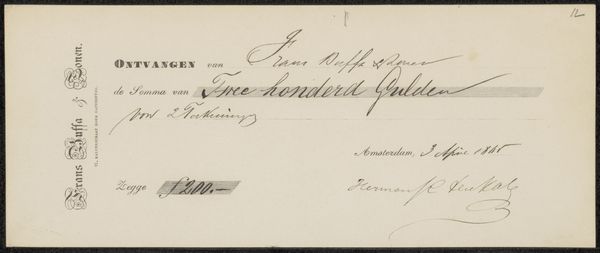

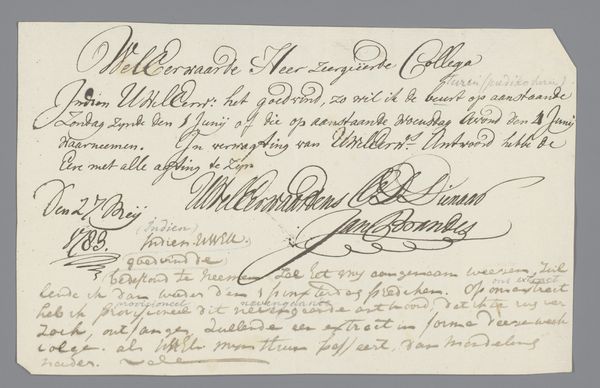

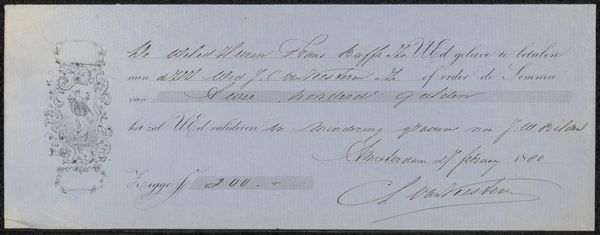

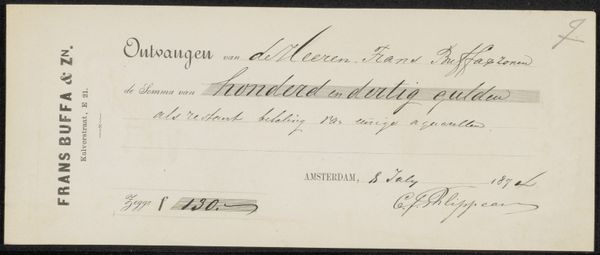

drawing, paper, ink

#

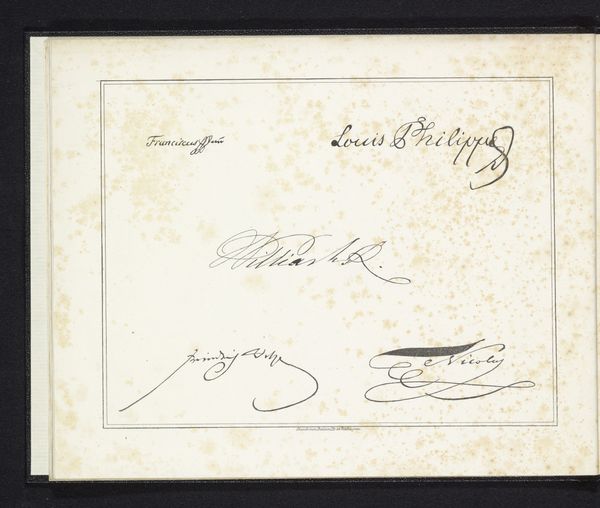

portrait

#

drawing

#

paper

#

ink

#

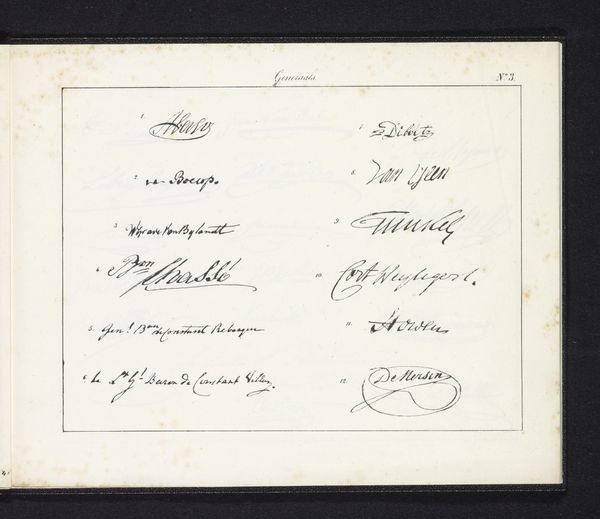

calligraphy

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

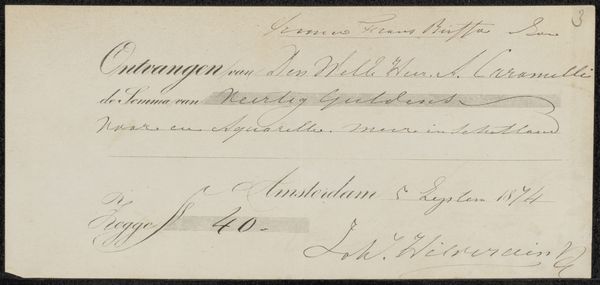

Editor: Here we have what’s called "Kwitantie voor Cornelis Springer," possibly from 1863, credited to Frans Buffa en Zonen. It's a drawing made with ink on paper. It looks like a receipt, and the elegant calligraphy gives it a formal yet intimate feel. What do you see in this piece, considering its apparent function as a mundane financial document? Curator: This seemingly simple receipt offers a powerful glimpse into the 19th-century art world, revealing complex relationships between artists, dealers, and the economy. What does it mean for artistic labor when it becomes so intertwined with commercial exchange? The drawing becomes more than just a receipt; it signifies how artists navigate their place within a capitalist system. How does the very act of documenting a financial transaction—the ‘kwitantie’ itself—influence our understanding of art’s value, its purpose, and who benefits from it? Editor: I never thought about a receipt being revealing about labour! Is there any significance to Springer being named? Curator: Absolutely. Springer, as the recipient of the funds, was likely a client, perhaps even a patron of Frans Buffa en Zonen. Recognizing Springer invites us to examine relationships between commerce and creativity in the cultural realm, asking questions such as: Whose art is funded? What kind of art can receive support? Who defines those financial avenues in art? And, fundamentally, does reliance on capitalist funding dilute an artist’s socio-critical perspective? Editor: That’s a really insightful perspective. I’ll definitely look at these kinds of works in a different light from now on. Thank you. Curator: And thank you. It's by posing these questions that we unveil hidden societal frameworks and power relationships encoded within works of art.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.