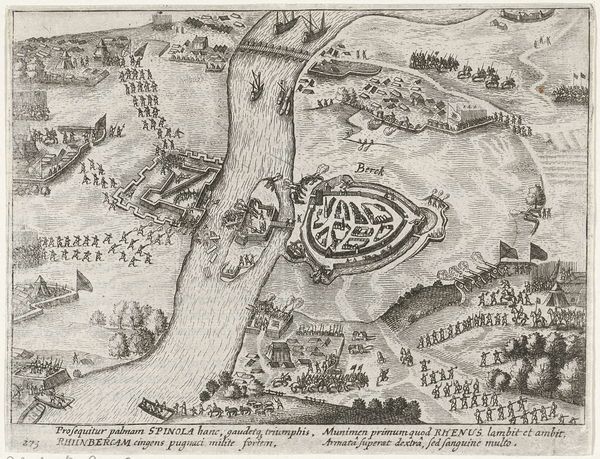

print, engraving

#

pen drawing

#

dutch-golden-age

# print

#

cityscape

#

history-painting

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 136 mm, width 175 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

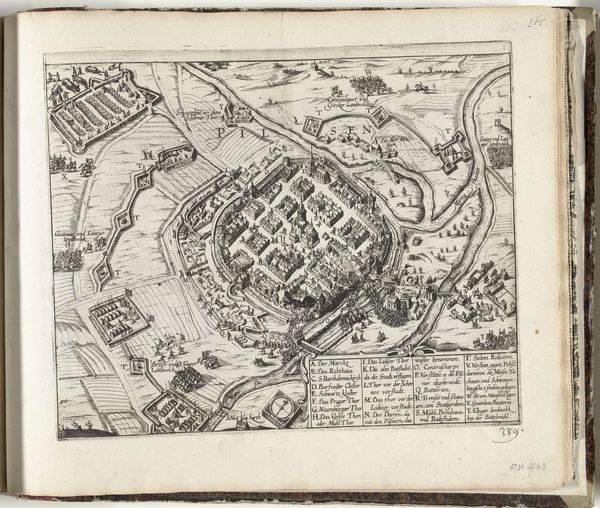

Curator: At first glance, this rendering of a siege evokes an uncanny sense of both vulnerability and immense power. It's meticulously detailed, almost diagrammatic, with this tight, circumscribed city facing external military might. Editor: Indeed. What we have here is an engraving, likely a print, titled "Oldenzaal veroverd door Spinola, 1605," dating back to somewhere between 1613 and 1615. The piece currently resides in the Rijksmuseum collection, and, tell me, doesn’t the scene depicted make you consider the gendered nature of warfare and urban planning? Curator: How so? Editor: The city, envisioned as enclosed, almost womb-like, being aggressively penetrated and conquered by decidedly masculine forces. These historical depictions, like this one, reinforce not only historical power dynamics, but subtly imply inherent inequalities along gendered lines. How does this specific historical event shape our perceptions of safety and invasion, power and vulnerability? Is Oldenzaal merely a place, or does it symbolize the perpetual threat of invasion experienced by the powerless? Curator: I see your point. Considering its context in the Dutch Golden Age, one also wonders about the role this image played in constructing national identity, fueling political sentiments during a time of significant social and political upheaval. These aren't just artistic representations, are they; they are strategic tools in the game of power. Who benefited from disseminating this narrative? Editor: Precisely. Furthermore, I wonder how much the ‘artist’ served as a conduit for power? The clean, illustrative style suppresses a sense of individual artistry, pointing towards a propagandistic aim—that is the power of social, cultural, and institutional forces at play. This rendering acts as a document, carefully manipulated for consumption, erasing individual stories to bolster broader national narratives. Curator: I leave here with more questions about who owns history and who gets to tell its story through images such as these. Editor: Yes, the political work imagery can accomplish. We leave with the understanding of the power inherent to the image as an instrument of power.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.