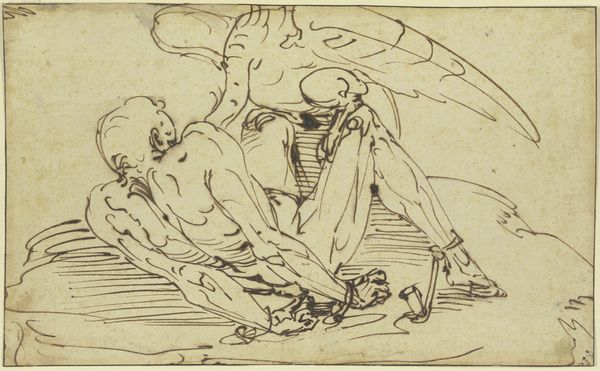

drawing, print, etching, ink

#

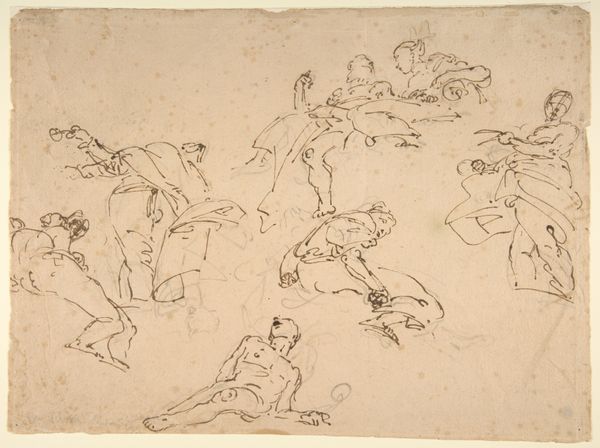

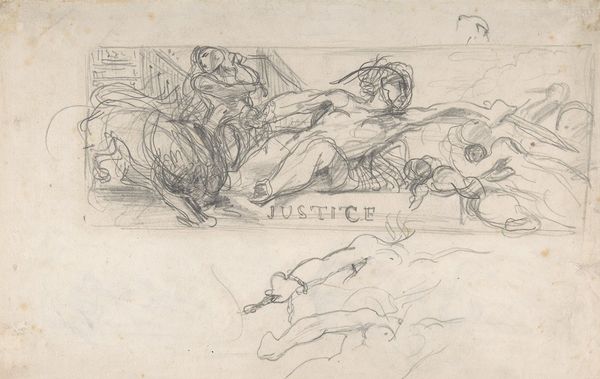

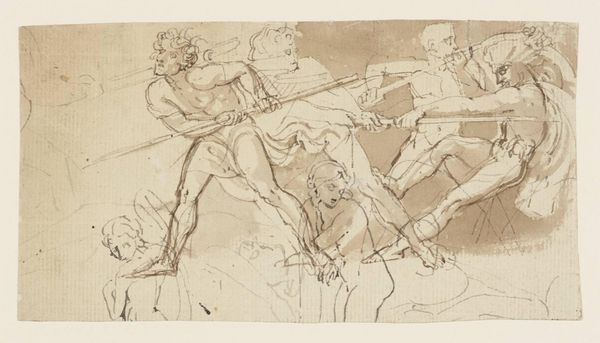

drawing

#

narrative-art

# print

#

pen sketch

#

etching

#

landscape

#

figuration

#

ink

#

symbolism

#

history-painting

#

nude

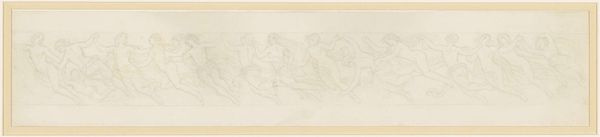

Dimensions: 3 x 8 3/16 in. (7.6 x 20.8 cm)

Copyright: Public Domain

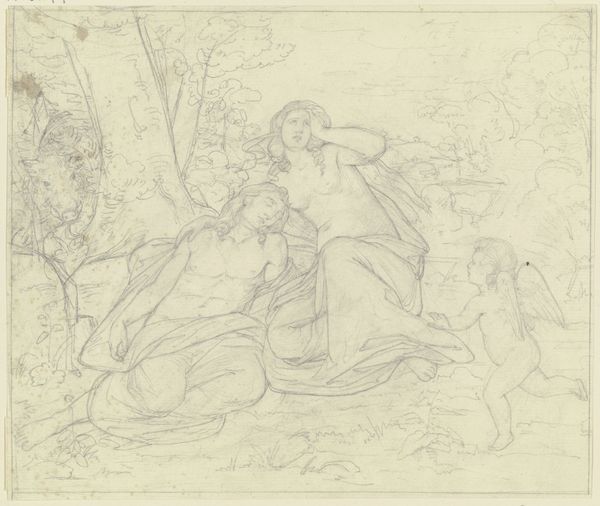

Curator: Here we have Max Klinger's "The Release of Prometheus," created sometime between 1870 and 1920. It's an etching, using ink and a fine pen, currently residing at the Metropolitan Museum. Editor: My first thought? Stark. Desolate. And look at that precise linework – it feels almost surgical, given the subject. Curator: Absolutely. Klinger, you know, he was wrestling with some pretty heavy ideas—the plight of humanity, the artist's role, societal injustices. Here, he tackles the myth of Prometheus. That defiant figure who dared to gift fire, knowledge, to humankind. And for his trouble? Chained to a rock, his liver perpetually devoured. Editor: The eagle represents, of course, the instruments of power. A brutal process of repetitive consumption made physical by that huge sharp beak and all the artist tools to make it believable, which is so compelling as this etching makes you witness the event repeatedly. The labor to punish labor! It is intense. I also cannot dismiss that the material aspect also is represented. It is not an oil painting or marble, it is only print work on paper! Which in Klinger's art is no more than one single step in an infinitely long work process, but here also represented on one piece. Curator: Yes, that restrained medium contrasts starkly with the grand myth. And note the angel comforting the tortured Titan; it almost creates a sense of tenderness amidst the suffering. Do you read a symbol of hope, or merely resignation, into that inclusion? Editor: Hope perhaps... It also has a bitter note. See how delicate, fragile she seems in front of Prometheus. The labor here of producing is being represented in this very light print and a reminder that all of those Greek stories of glory and heroes would just remain stories and not a fact for eternity. So she is trapped there comforting that soul and can do little other than that. She’s stuck. Curator: An interesting interpretation. It shows his nuanced ability to imbue mythological figures with palpable vulnerability. Klinger encourages a deep contemplation on both the potential and the torment inherent to human progress. Editor: Thinking about the process involved, and seeing those lines – countless passes to build that scene, to convey torment in material form—I appreciate the artistry here. Not just in its subject matter but the translation of that intense feeling into an artifact we are studying and observing right now, where that man that helped us and his pain become just stories. It's powerful, how that's etched into paper and passed on into modern eyes. Curator: Well said. It really is a piece that gets under your skin, forcing us to reconsider the cost of innovation, of creation itself. Editor: I'm taking away a renewed respect for the physical making involved—not just the concept, but the toil.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.