![Francesco I d'Este Assists His Subjects with Great Generosity During the Great Famine of 1648 and 1649, from L'Idea di un Principe ed Eroe Cristiano in Francesco I d'Este, di Modena e Reggio Duca VIII [...] by Bartolomeo Fenice (Fénis)](/_next/image?url=https%3A%2F%2Fd2w8kbdekdi1gv.cloudfront.net%2FeyJidWNrZXQiOiAiYXJ0ZXJhLWltYWdlcy1idWNrZXQiLCAia2V5IjogImFydHdvcmtzLzE0OTQ4Nzg3LTZiNjEtNGYyMi05YTY5LTIwOWNhMGY2Y2U0Ny8xNDk0ODc4Ny02YjYxLTRmMjItOWE2OS0yMDljYTBmNmNlNDdfZnVsbC5qcGciLCAiZWRpdHMiOiB7InJlc2l6ZSI6IHsid2lkdGgiOiAxOTIwLCAiaGVpZ2h0IjogMTkyMCwgImZpdCI6ICJpbnNpZGUifX19&w=3840&q=75)

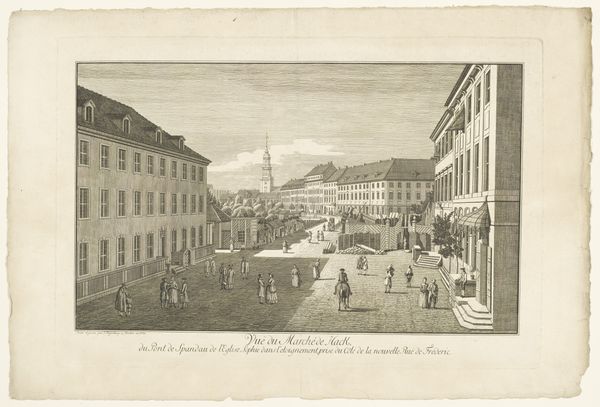

Francesco I d'Este Assists His Subjects with Great Generosity During the Great Famine of 1648 and 1649, from L'Idea di un Principe ed Eroe Cristiano in Francesco I d'Este, di Modena e Reggio Duca VIII [...] 1659

0:00

0:00

drawing, print, etching

#

drawing

#

baroque

# print

#

etching

#

landscape

#

figuration

#

horse

#

line

#

cityscape

#

history-painting

Dimensions: Sheet: 4 13/16 × 6 5/16 in. (12.3 × 16 cm) Plate: 4 3/4 × 6 1/4 in. (12 × 15.8 cm)

Copyright: Public Domain

Curator: This etching by Bartolomeo Fenice, dating back to 1659, is part of a series titled, “L’Idea di un Principe ed Eroe Cristiano in Francesco I d’Este,” and it depicts Francesco I d’Este assisting his people during the famine of 1648 and 1649. What strikes you first? Editor: The layout is immediately striking, as it uses this bird's-eye perspective of an active piazza in which suffering and charity intersect. This feels very characteristic of its time. I'm thinking of the collective visual memory of the plague imagery throughout the Renaissance and Baroque periods. It seems, despite its celebration of a leader, tinged with unease. Curator: That's insightful. Contextually, we can view it through the lens of power and representation. Francesco I is actively constructing his image as a benevolent ruler during a time of crisis, a narrative strategically employed in an era marked by immense social and economic disparity. Consider the positioning of figures within the composition; who is given precedence? Editor: Note the repetition of the oxen cart motifs that emphasizes a very persistent and traditional symbol for hard work, abundance, but, here, scarcity. The figures reach, receive, accept and that central gifting motif, I see echoes of ancient and religious tropes regarding generosity of spirit and sacrifice in leadership. This connects deeply with collective cultural expectations of rulers. Curator: Absolutely. Further deconstructing this image, we observe how it frames the historical moment through the prism of early modern statecraft. The intentional staging—a generous ruler at the forefront, humble subjects receiving aid, the city as a backdrop—all solidify the Duke’s position and power, a visual reinforcement of hierarchy during a time of vulnerability. It makes me think of theories around the construction of public image, how art can be wielded as propaganda, essentially. Editor: Yes, the imagery of the 'good leader' is quite literally embodied through composition and symbolism. The suffering of a nation, while undeniably present, seems almost designed as the backdrop for this portrayal of moral authority. One might even say that the artist, whether consciously or not, transforms very human experiences into political rhetoric. Curator: Precisely. The complexities within this piece provoke us to contemplate on representation and power dynamics, its message woven with layers of historical, social and political understanding. Editor: It encourages us to view historical art as a complex reflection of cultural aspirations and socio-political dialogues.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.