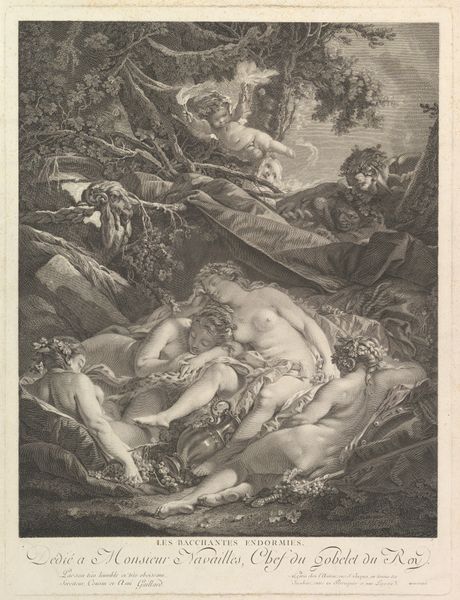

Dimensions: height 551 mm, width 403 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: This is Jean Pelletier’s "Narcissus," created sometime between 1746 and 1780. It's an engraving. Editor: It’s captivating. The figure almost melts into the landscape, yet there's such a strong interplay between light and shadow giving it a very baroque feel. What draws me in is the mirroring—the material reflection as the central theme. Curator: Indeed. Pelletier masterfully uses the engraving process to mimic the subtleties of light, which contributes greatly to the atmosphere. Consider the availability of copper plates for printmaking at the time. The labor involved in the meticulous etching… it speaks volumes about the value placed on reproductive prints as disseminators of imagery in 18th-century society. Editor: Absolutely. This print would have circulated widely. Think about how the story of Narcissus itself was viewed then. It’s a morality tale, certainly, about vanity and self-obsession. How was it received by a society on the brink of revolution? Were they concerned with their own reflections, both literally and figuratively? Curator: I think so. And there's also the performative aspect. The original myth gains a visual interpretation and circulation. The print as a medium enables discussion about identity and performance within the social structures of the era. Who gets to be "seen"? Editor: The print format certainly democratized the image to an extent, though its consumption would have still been primarily among the privileged classes, further complicating our understanding of visual and cultural dissemination during this time. How do you see this artwork being shown in institutions now? Curator: It presents challenges. Displaying a print within the context of, say, photography and other image reproduction processes might lead to insightful dialogues regarding labor and technology. Its relative scale should also influence the audience experience of intimacy and contemplation. Editor: Thinking about its public role then, I feel its commentary extends beyond narcissism as personal failing to include reflections on wealth, social hierarchies, and societal vanity as a whole. The materiality allows it a further engagement as to who has the materials, such as access to artistic production in 18th-century. Curator: Absolutely, it seems even something as small as an engraving print, reveals the society’s economic state during the eighteenth-century through the material choices behind it. Editor: A great reminder that appearances aren't everything, which becomes quite salient with regards to social hierarchies!

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.