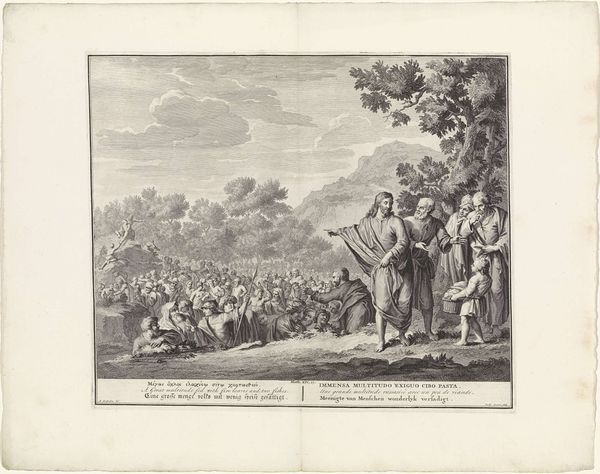

Gezicht op de boslaan met de drie bruggen voor het Huis ter Nieuburch in Rijswijk, 1697 1697

adriaenschoonebeek

Rijksmuseum

print, engraving

baroque

landscape

cityscape

genre-painting

engraving

Dimensions: height 233 mm, width 298 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: Adriaen Schoonebeek’s engraving, “View of the boulevard with the three bridges in front of the Huis ter Nieuburch in Rijswijk,” created in 1697, offers a fascinating glimpse into Dutch society at the end of the 17th century. Editor: My first impression is the incredible detail for an engraving, capturing the bustling energy of what seems like a formal promenade. The stark black and white lends a certain severity, doesn’t it? Curator: Absolutely. Schoonebeek was a master engraver, known for his precision. Here, he depicts the avenue leading to the Huis ter Nieuburch, a significant location where the Treaty of Rijswijk was signed that same year. The event obviously brought many important people. Notice the diverse social classes represented – from the gentry in their carriages to commoners strolling along the path. It shows the importance of the location and events held here at that moment in time. Editor: I notice that, but I think the perspective emphasizes the wealth on display more than a shared public space. I see a structured hierarchy played out within the park's design, a very deliberate choreography of power in how he organized the population in relation to the bridges and boulevard leading to the Huis ter Nieuburch itself. How does Schoonebeek position this piece politically? Curator: That's a very astute observation. His patrons likely wanted a piece to capture the significance of the treaty and emphasize the success of Dutch diplomacy, even projecting the wealth on display. So, there's an element of social commentary at play but certainly not as critical as you imply. The print, by circulating this imagery, also functions as propaganda, legitimizing the ruling elite and the Dutch Republic's role on the European stage. Editor: Exactly. It highlights how artistic choices, like depicting such a diverse assembly on this central thoroughfare, contribute to broader narratives of power and identity. Even what appears like an inclusive vista serves to underscore the exclusive benefits of those in charge. That location must have served as more than just landscape. Curator: I agree. The location holds a specific historic role. We must ask, how does it use the visual vocabulary of Baroque landscape to affirm a specific socio-political reality? Thank you for those astute comments. Editor: Likewise. It’s been an insightful conversation to see those points clarified, to understand that snapshot of Dutch history and reflect on its legacies.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.