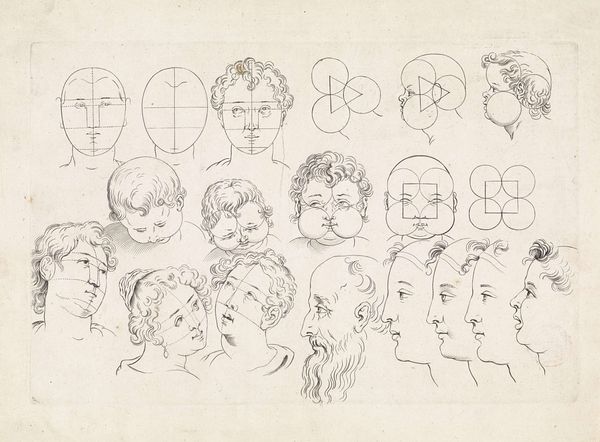

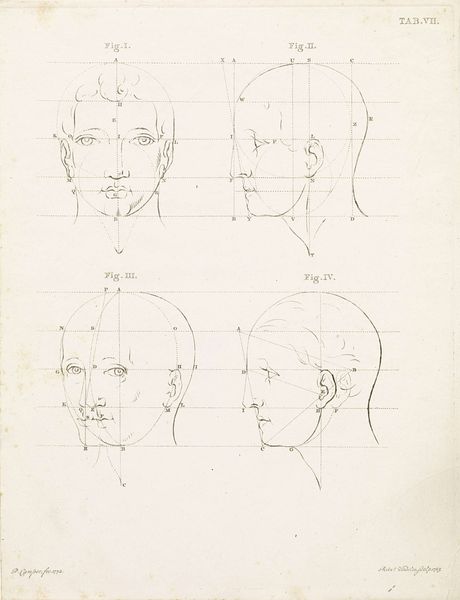

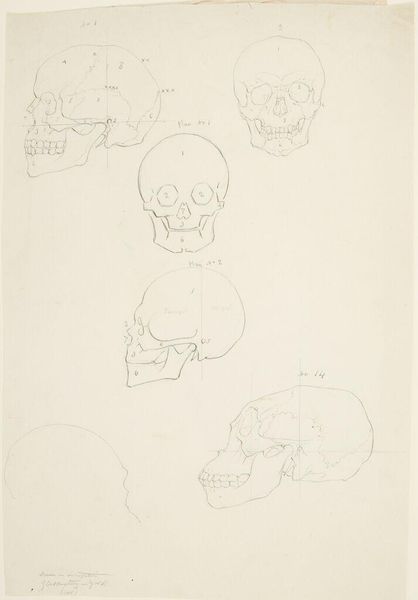

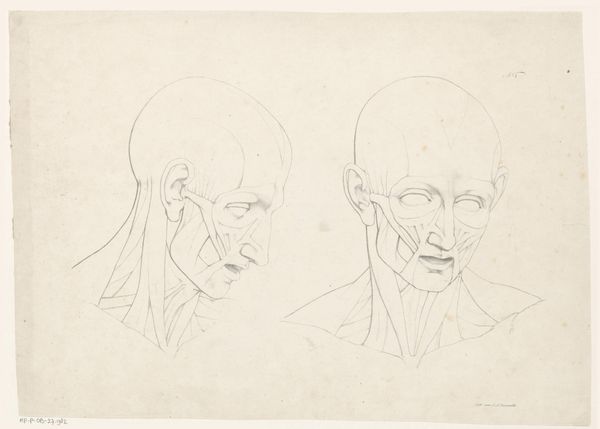

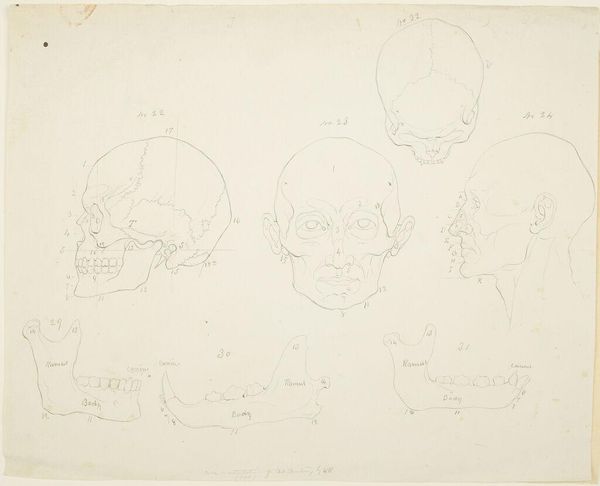

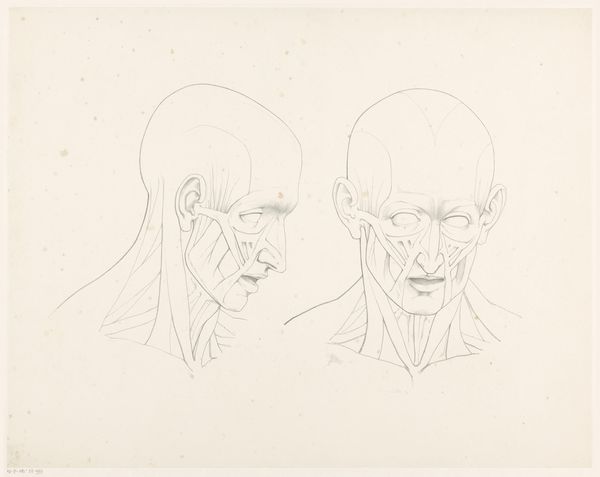

drawing, paper, pencil

#

portrait

#

drawing

#

neoclacissism

#

paper

#

form

#

pencil

#

line

#

history-painting

#

academic-art

#

realism

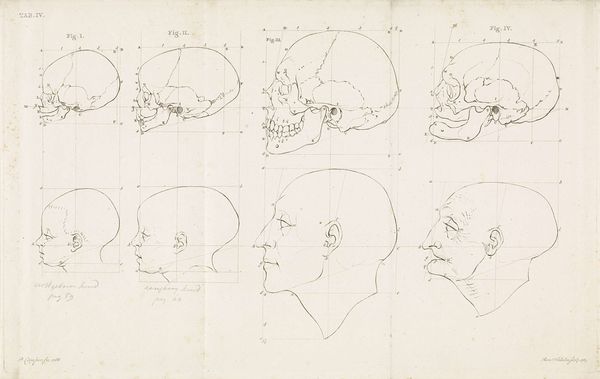

Dimensions: height 268 mm, width 430 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

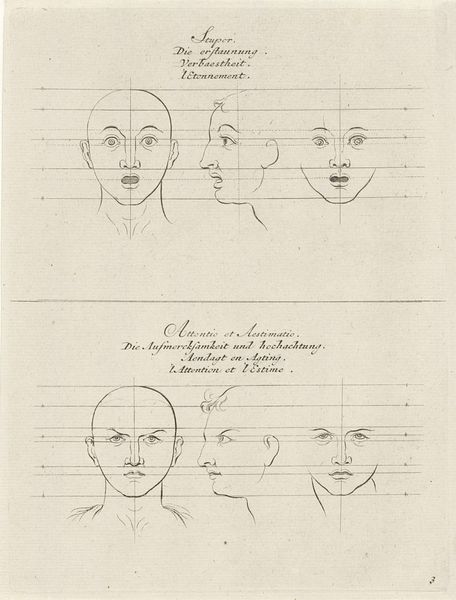

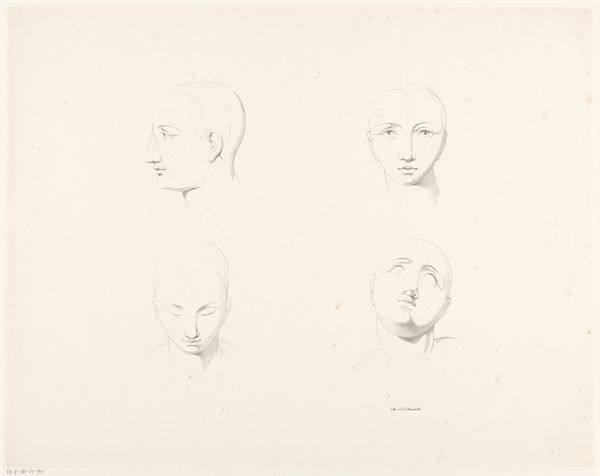

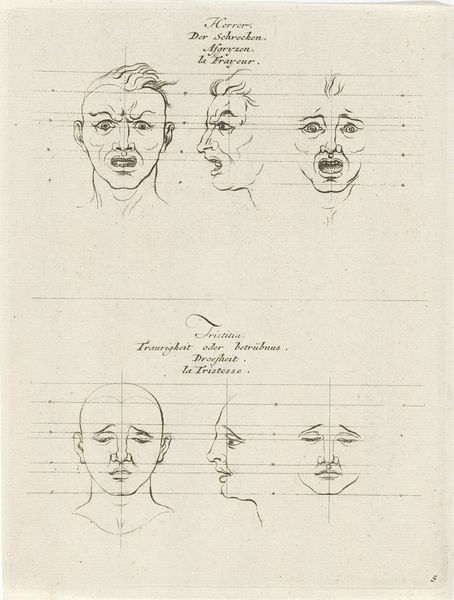

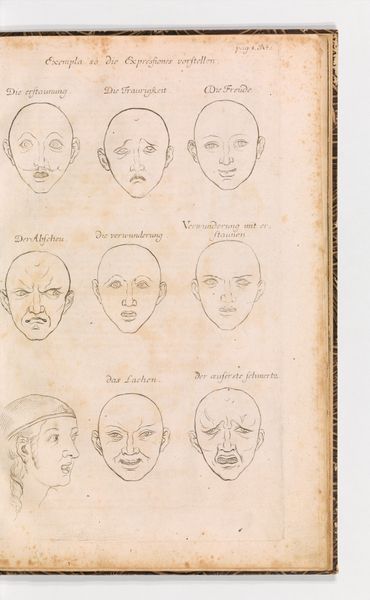

Editor: We’re looking at Reinier Vinkeles' "Study of a Monkey Head and a Human Head and Skull," created in 1786 using pencil on paper. It feels like an anatomical study, laid out with precision. What do you see in this piece? Curator: This drawing is not just an anatomical study; it’s a product of the Enlightenment, steeped in the era's obsession with classification and the great chain of being. Vinkeles positions the monkey and human head alongside the skull – asking us to consider what separates us, and more pointedly, who defines those boundaries. Do you see any clues in the way they are drawn? Editor: Well, they’re all drawn with the same level of detail and scientific precision, using that grid system. It makes them feel…comparable. Curator: Exactly. The grid, a symbol of Enlightenment rationality, attempts to neutralize the subjects, to make them comparable under the guise of objective observation. Yet, think about who got to be "objective" back then. How might the drawing's focus on classifying different heads perpetuate power structures related to race and species? Editor: So, it's less about objective science and more about reinforcing existing social hierarchies? Curator: Precisely. The seemingly neutral act of drawing and categorizing becomes a tool for asserting difference, reinforcing the supposed superiority of one group over another. Consider how this impulse to classify and order informs our understanding of identity even today. Editor: I never would have thought about it that way. I saw it as just a scientific study, but now I realize how much more it’s communicating. Curator: That's the power of engaging with art from a critical, historical perspective. It challenges us to question the supposed neutrality of knowledge and art itself.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.