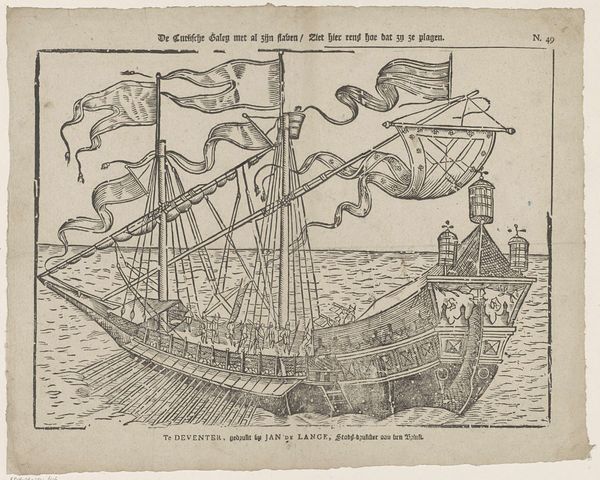

't Zijn alle geen boeven die men zoo noemt / Die ter galije zijn gedoemt 1748 - 1761

0:00

0:00

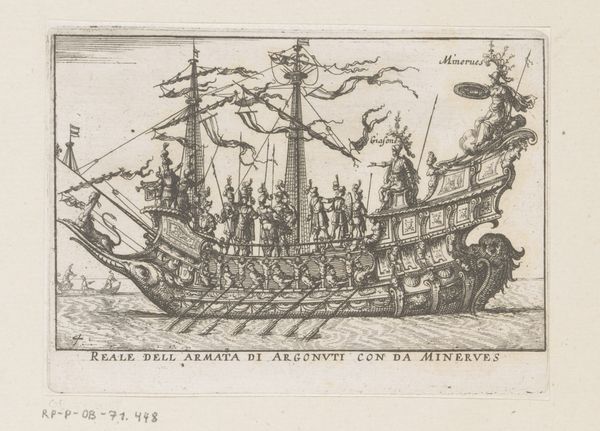

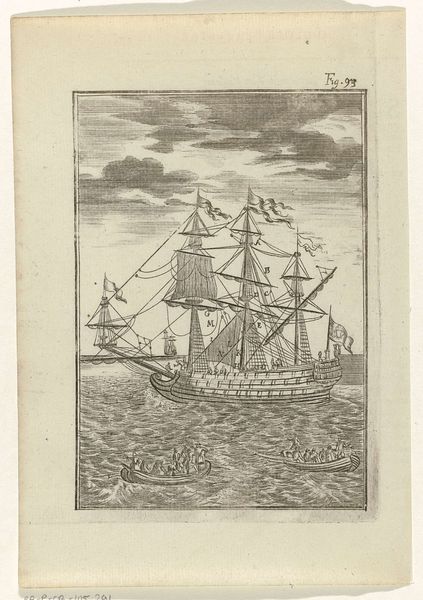

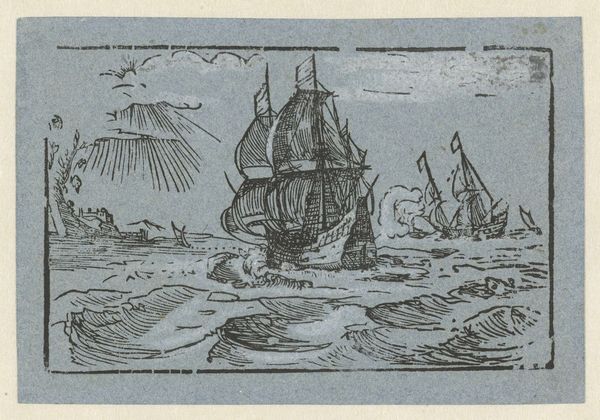

drawing, print, intaglio, ink, engraving

#

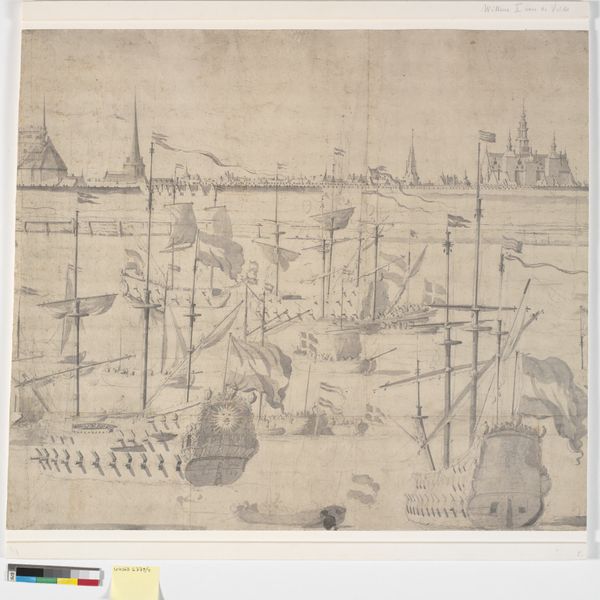

drawing

#

aged paper

#

toned paper

#

blue ink drawing

#

narrative-art

#

baroque

#

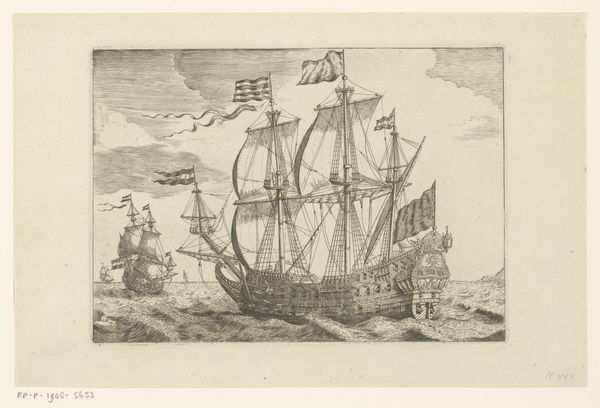

dutch-golden-age

# print

#

intaglio

#

old engraving style

#

figuration

#

personal sketchbook

#

ink

#

ink colored

#

line

#

sketchbook drawing

#

watercolour illustration

#

history-painting

#

storyboard and sketchbook work

#

sketchbook art

#

engraving

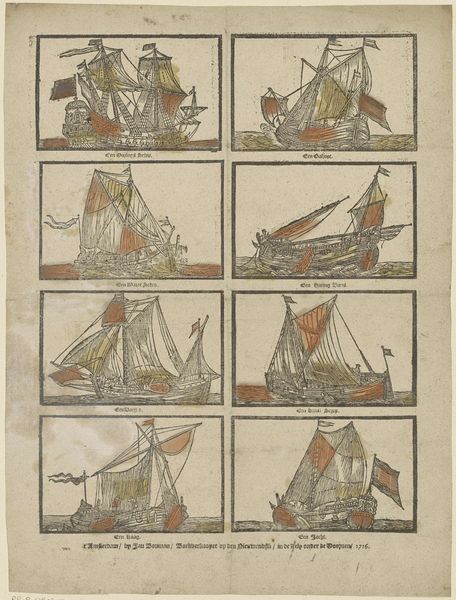

Dimensions: height 310 mm, width 416 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

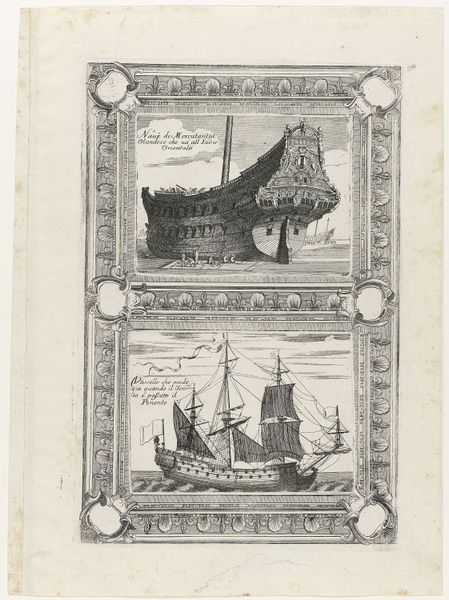

Editor: So, this engraving from between 1748 and 1761, titled "'t Zijn alle geen boeven die men zoo noemt / Die ter galije zijn gedoemt" by Abraham van der Putte, depicts a galley ship. The detail is impressive, but I'm struck by how it almost seems to romanticize such a vessel – a floating prison, really. What's your interpretation? Curator: I see this piece as a commentary on power and justice, wrapped within maritime iconography. The title translates to "They are not all villains who are condemned to the galleys." Consider the period: the Dutch Golden Age had waned, but maritime power remained significant. Do you think the artist is making a statement about who gets branded a criminal and the inherent inequalities in that system? Editor: That’s a compelling point. The people manning the ship appear almost uniform, faceless even. Are they meant to represent a specific class, or perhaps the blurring of identities that occurs within oppressive systems? Curator: Exactly. Think about Foucault’s concept of power – how it shapes identity and disciplines bodies. These galley slaves are stripped of their individuality, their labor fueling the machinery of the state. And what of the flags? Who benefits from this forced labor and maritime dominance? Editor: The flags could definitely symbolize national identity and trade interests, possibly even the exploitation of others for economic gain. Is the ornate border around the image possibly in contrast to the brutal reality depicted within? Curator: Precisely! The aestheticization of such harsh realities is a crucial element. It normalizes violence and exploitation, masking it beneath a veneer of order and prosperity. Doesn't this artwork, in a way, participate in that masking, even while potentially critiquing it? Editor: That's a challenging but valid question. I see how the image operates on multiple levels, both revealing and concealing the injustices it depicts. I'm grateful to know the way to understand such topics, like identity, race and politics by connecting this to intersectional narratives! Curator: And that complexity is precisely where the power of art lies – in forcing us to confront uncomfortable truths and question the very narratives we inherit. The personal IS political.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.