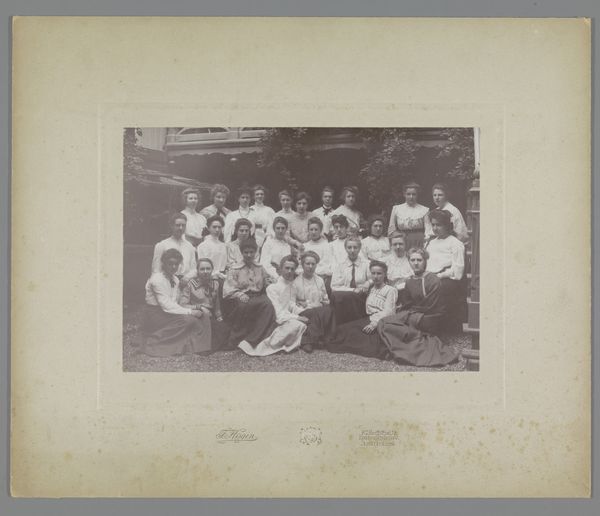

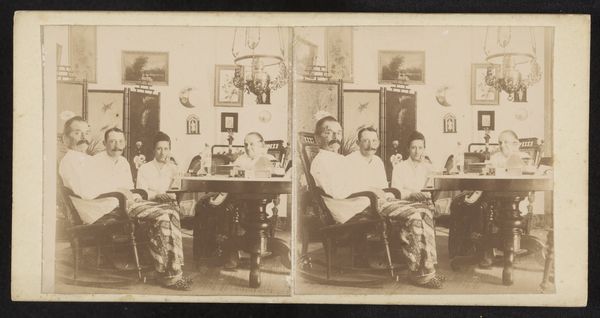

photography, gelatin-silver-print

#

portrait

#

photography

#

group-portraits

#

gelatin-silver-print

#

genre-painting

#

realism

Dimensions: height 72 mm, width 80 mm, height 88 mm, width 178 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: Here we have Robert Julius Boers' photograph titled "Familieportret," created sometime between 1900 and 1922. It's a gelatin silver print currently residing here at the Rijksmuseum. Editor: My initial impression is of a rigid formality juxtaposed with an undercurrent of colonial tension. The sepia tone lends a dreamlike, historical distance. Curator: Absolutely. Boers, while working within the conventions of a family portrait, was also capturing a complex social dynamic. These genre paintings, photographs like these, were circulated and received very differently depending on the audience, contributing to both domestic memories and perhaps colonial propaganda. Editor: Considering postcolonial theory, the racial hierarchy is unmistakable, with the white family positioned prominently while people of color are relegated to the background, some in servant roles. This image is fraught with implications. The arrangement suggests power dynamics at play. Curator: And what about the children? How do they complicate or reinforce these dynamics? What might that small boy seated at the front, gazing directly at the viewer, be telling us? The composition itself feels staged to project authority and prosperity, mirroring Dutch colonial governance at the time. This photograph is far more than just a snapshot of a family. It becomes a window into understanding the public role of these types of images. Editor: Exactly. It forces us to grapple with the representation of power, race, and identity during that era. We can see the photograph functioning as a symbol of control. And in that context, even small stylistic choices, such as the subjects’ gazes, can reinforce such social messages. It serves as a visual document of colonialism's pervasive impact, doesn't it? Curator: Indeed. By understanding the image's cultural history, we recognize that it is never really a simple, objective recording of reality but reflects how imagery shaped social order at the time. Editor: The visual strategies utilized serve a propagandistic goal. These dynamics need interrogation to understand what intersectional narratives of gender, class, race, and even sexuality might have occurred behind the camera as well. Curator: I agree. It compels us to confront the legacies and power relations that shaped artistic portrayals and reception in these images. Editor: For me, I’m left pondering the untold stories that hide in the shadows of this photograph, making it more urgent than ever to re-evaluate historical images through contemporary perspectives.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.