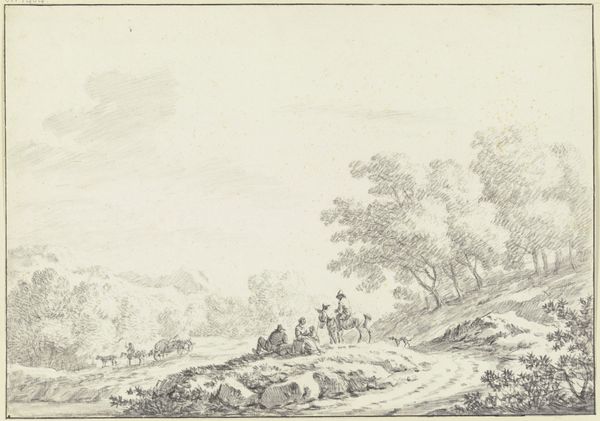

drawing, etching

#

drawing

#

etching

#

landscape

#

etching

#

figuration

#

romanticism

Dimensions: height 177 mm, width 269 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: So, we’re looking at "Hertenjacht" – that's “Deer Hunt” in Dutch – by Guillaume Joseph Vertommen, made sometime between 1825 and 1863. It's a drawing and etching. And my first thought? That the world is a beautiful, and inevitably violent, place. Editor: Violence is what strikes me, too, although that it comes through such delicate mark making. What paper and etching plate did Vertommen have at hand? There’s a contrast between the hunt depicted and the subtle labour of the production involved. Curator: Interesting, yes. You know, when I look at this, I don't just see hunters chasing deer; I see the fleeting moments of existence. The dogs running…that blur of energy! Vertommen captures the raw power of nature, don’t you think? Editor: Well, I do think Vertommen chose the hunt to depict how labour itself can also involve violent interaction with the land, which reminds us the land must in turn sustain labour itself. The raw material extraction from a zinc or copper plate must, itself, be mined from the earth. Curator: So, we're talking about romanticism, which often celebrated idealized landscapes. But Vertommen also captures this restless feeling. What are your thoughts about his line work? Editor: Look at those finely rendered trees! Romanticism aside, let's consider the socio-economic situation and access to specialist tools necessary for even these expressive yet disciplined markings. Consider the artist as entrepreneur or as craftsperson—a vital question. Curator: Precisely. Because I find in Vertommen a very curious sense of something about to be lost forever. You can see it in the almost frantic detail. It's a whisper of the industrial revolution knocking at the door of this wild scene. The old world is dying here. Editor: Ultimately, considering the paper the final print lands upon, it invites us to reflect on how, by producing etchings, Vertommen’s labour also contributes to logging, tree felling, paper mills and distribution networks – processes themselves potentially eroding romanticism’s ‘pure’ landscape? Curator: Right. Seeing this through a materialist lens is fascinating! Vertommen thought he was painting nature, or rendering the world—when actually, he was deeply caught up in the structures of capital, which also constitute ‘nature’. Editor: Exactly. So even as this small artwork feels timeless and self-contained, it remains the direct material trace of something that's both incredibly personal, and irrevocably interwoven with larger forces.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.