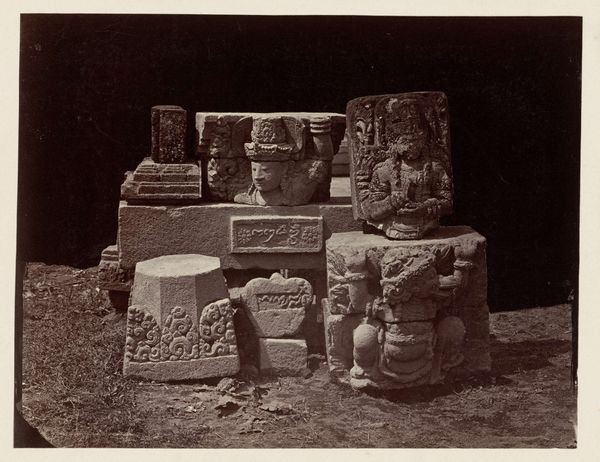

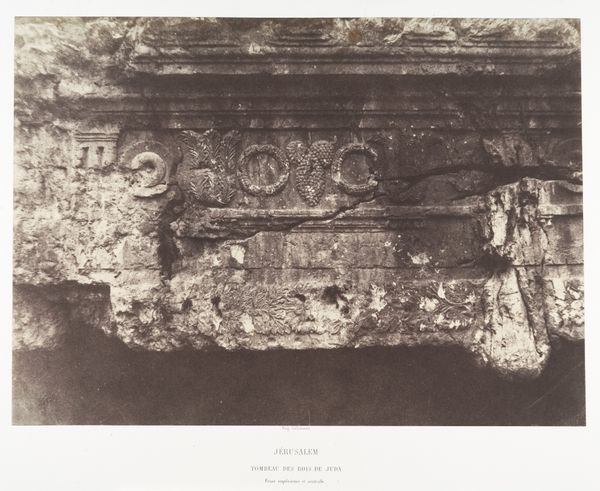

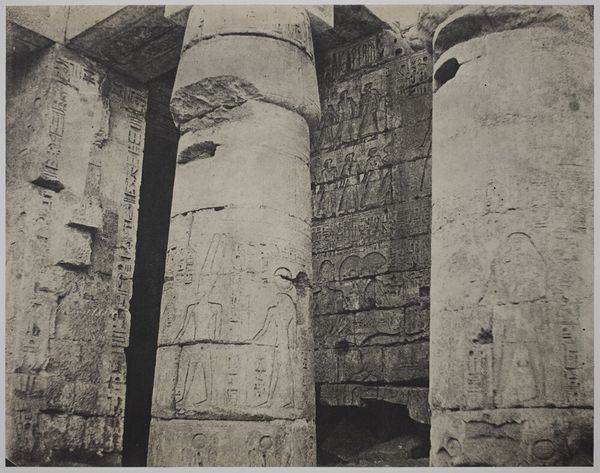

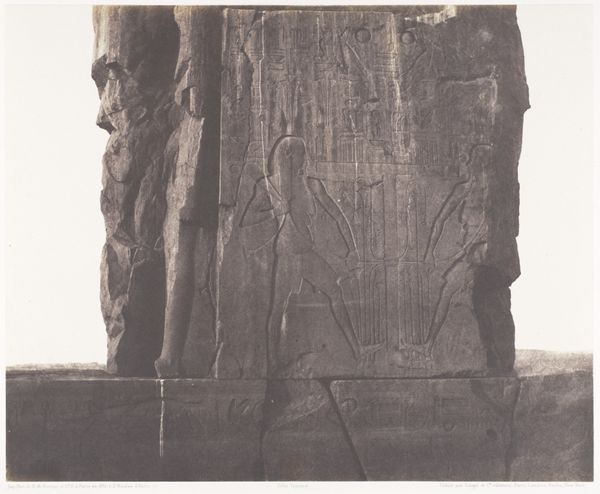

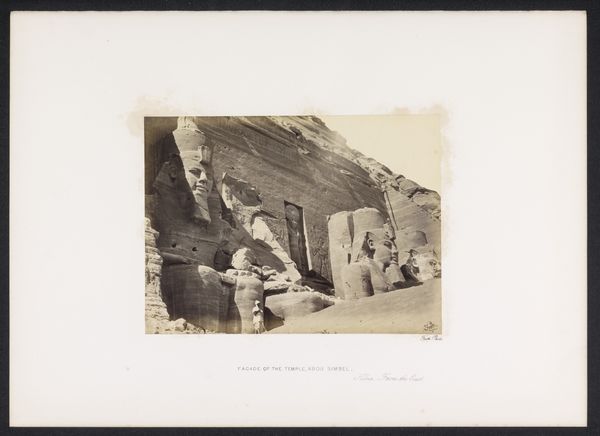

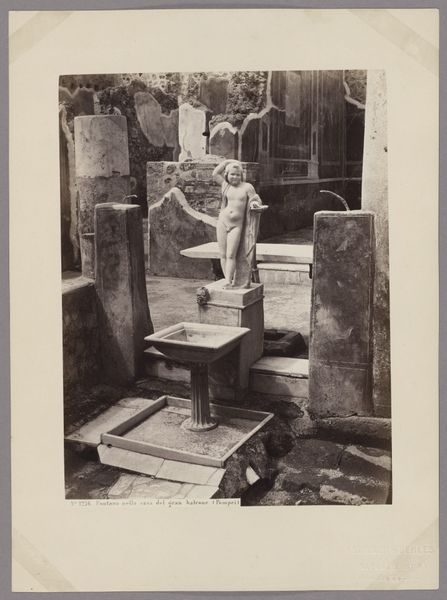

Jérusalem, Fragments judaïque et romain 1854 - 1859

0:00

0:00

photography, gelatin-silver-print

#

photography

#

ancient-mediterranean

#

gelatin-silver-print

#

history-painting

Dimensions: Image: 23.5 x 30.9 cm (9 1/4 x 12 3/16 in.) Mount: 44.8 x 59.7 cm (17 5/8 x 23 1/2 in.)

Copyright: Public Domain

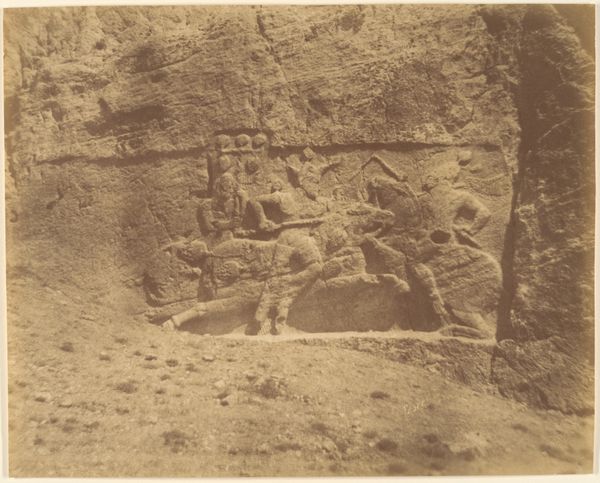

Editor: So, this photograph, "Jerusalem, Fragments judaïque et romain," was taken by Auguste Salzmann sometime between 1854 and 1859. It’s a gelatin silver print and depicts two…well, fragments, I suppose. They look like architectural details. There’s a real stillness and solemnity to the image. What historical weight do you think this piece carries? Curator: That stillness, as you put it, resonates deeply within its historical context. Salzmann was part of a wave of photographers commissioned to document archaeological sites in the mid-19th century. This was driven by European colonial interests, of course. Photography was seen as objective proof, but in reality, it served to bolster Western narratives about the Holy Land. Don’t you find it interesting how this early photographic technique attempts to lend an air of authenticity to objects already burdened with centuries of contested meaning? Editor: Absolutely. So the photograph itself isn’t just a record, but an argument of sorts? How did these images function in the political landscape? Curator: Precisely! Images like this one circulated widely through Europe and were often used to illustrate books and articles, shaping public perceptions and bolstering colonial claims. Salzmann wasn't merely capturing "truth," he was participating in a discourse about ownership and control. Think about it, the “fragments” themselves imply a past that’s been broken apart, waiting to be pieced back together - presumably by the West. Editor: That's fascinating, the idea that even the act of documenting could be an act of appropriation. What does it mean that this work now lives in The Met? Curator: The Met's acquisition of the work certainly invites questions about repatriation, ownership, and the legacies of colonial-era collecting practices. Editor: Thanks for highlighting this, I had not thought about these issues until now. It offers such a complex lens through which to view a seemingly simple photograph.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.