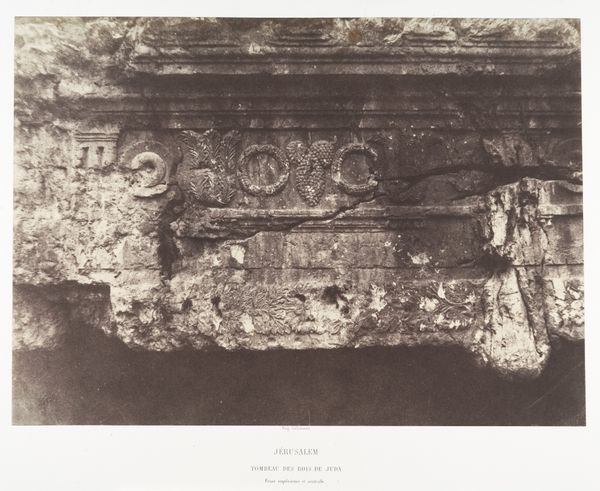

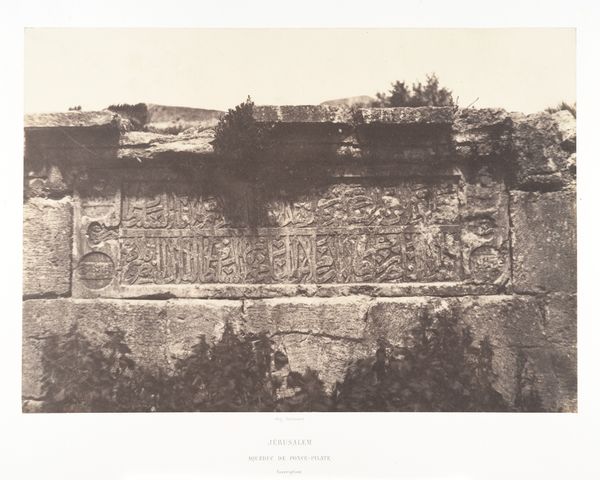

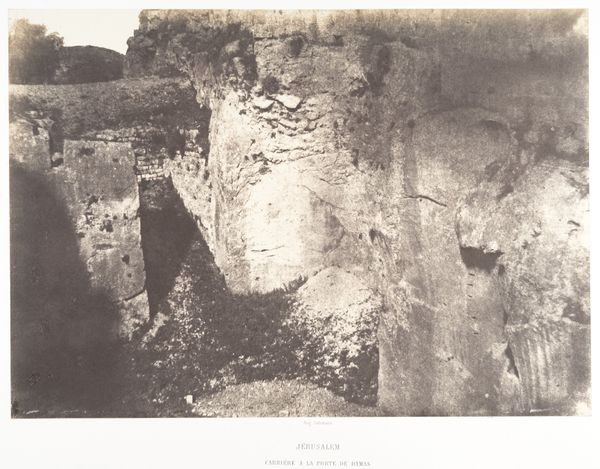

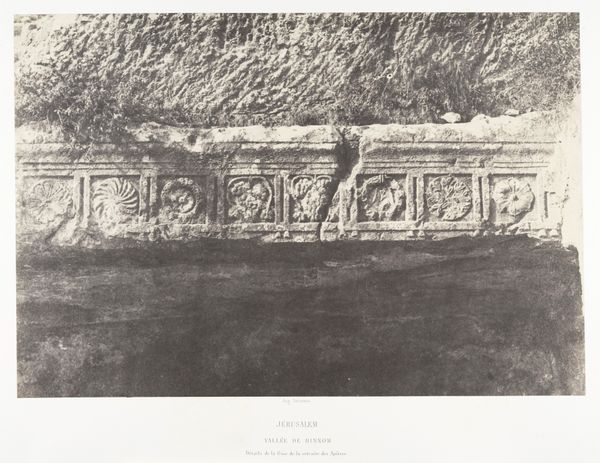

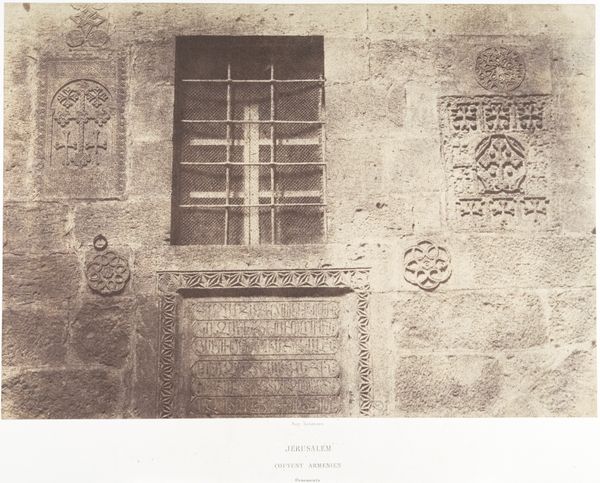

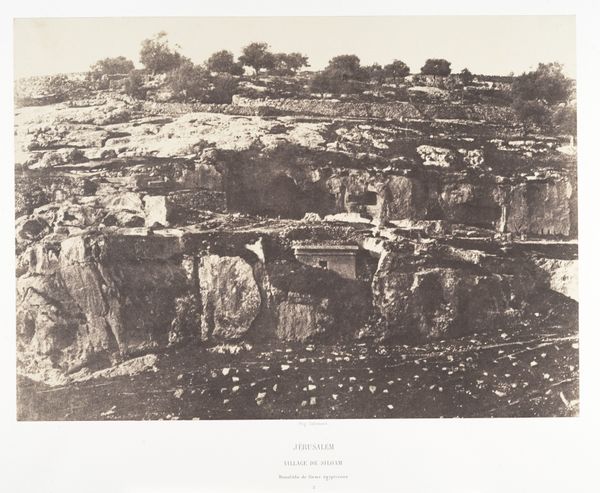

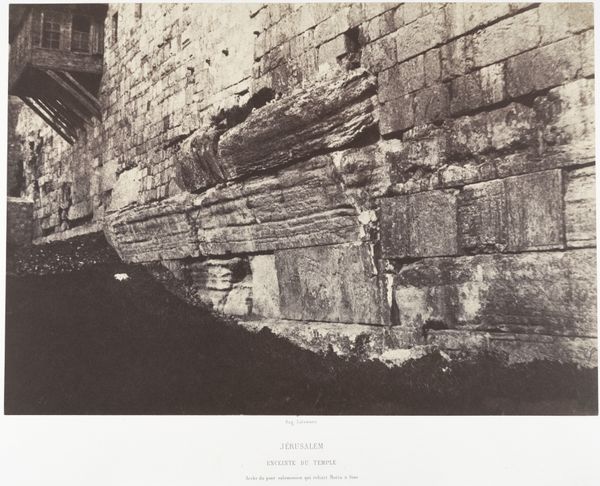

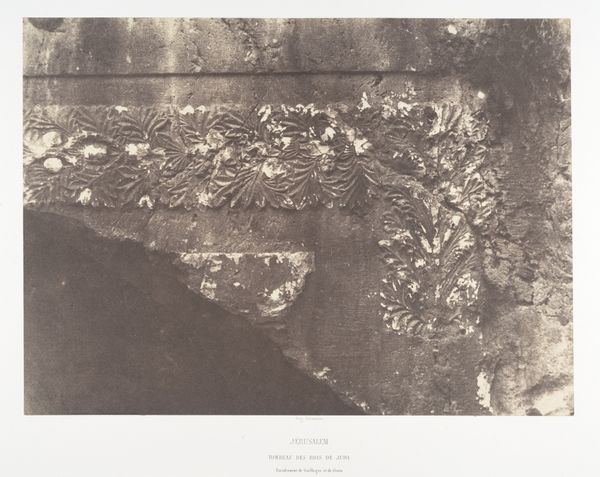

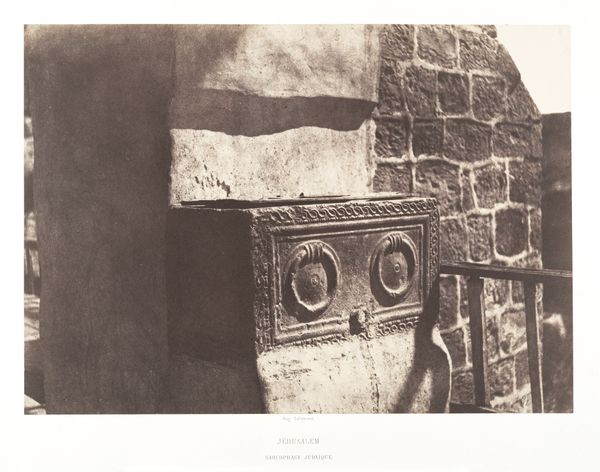

Jérusalem, Restes de scupltures judaïques 1854 - 1859

0:00

0:00

photography, site-specific, albumen-print, architecture

#

charcoal drawing

#

photography

#

ancient-mediterranean

#

site-specific

#

albumen-print

#

architecture

Dimensions: Image: 23.5 x 33 cm (9 1/4 x 13 in.) Mount: 44.5 x 60.6 cm (17 1/2 x 23 7/8 in.)

Copyright: Public Domain

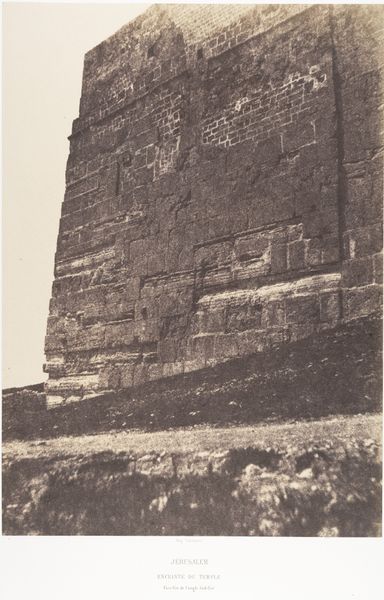

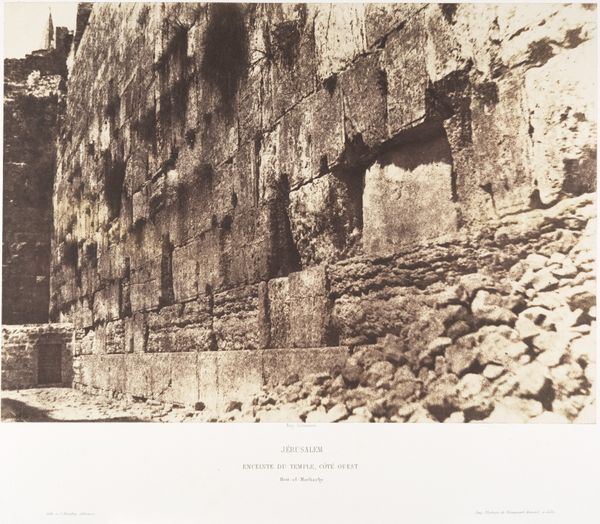

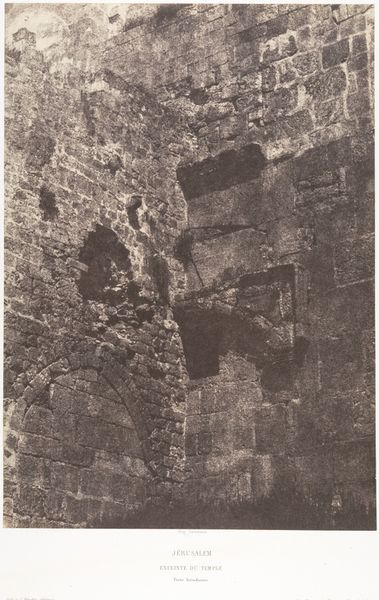

Curator: This is Auguste Salzmann’s "Jérusalem, Restes de sculptures judaïques," an albumen print dating from between 1854 and 1859. Editor: There’s a powerful, melancholy beauty to this image. It feels incredibly immediate, almost as if I were standing right in front of these ancient carved stones. Curator: Salzmann was a pioneer in using photography for archaeological documentation. This work speaks volumes about 19th-century European interests in the Holy Land, driven both by religious fervor and the burgeoning field of archaeology. Editor: You can almost feel the grit of the stone, the weight of the history etched into those carvings. What's interesting is how photography, a relatively new medium at the time, became instrumental in framing these sites. It almost commodifies these distant places and their past. Curator: Exactly. Salzmann’s photographs were presented as objective records, but of course, they're carefully composed interpretations, catering to a specific European audience keen on visualizing biblical narratives. Consider the print’s original exhibition context; these images circulated within academic societies and institutions, reinforcing particular understandings of the East. Editor: And the choice of albumen print would influence that. It’s a process demanding skilled labor, requiring specific materials, giving it an almost painterly quality. The final photograph isn’t just an image; it’s a crafted object designed to impress. Curator: Indeed. Moreover, the very act of photographing these “restes” or remnants reveals the colonial gaze, capturing and presenting these Jewish sculptures within a framework of European intellectual dominance. Editor: It prompts one to think about how these sculptures came to be “restes.” What kind of human labor produced, damaged, or perhaps deliberately destroyed them? There's so much about the making and unmaking implicit in this image. Curator: So while on one level, it served as documentary evidence, on another, it further codified a European historical perspective. Editor: Ultimately, I'm struck by the artistry behind its production – that tension between its supposed objective neutrality, and the hand that carefully crafted the final image we see. Curator: A collision of historical context, religious fervor, and emergent visual technologies make this work particularly compelling.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.