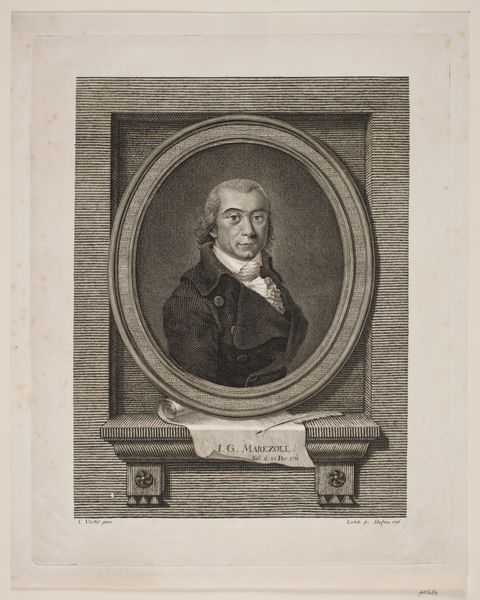

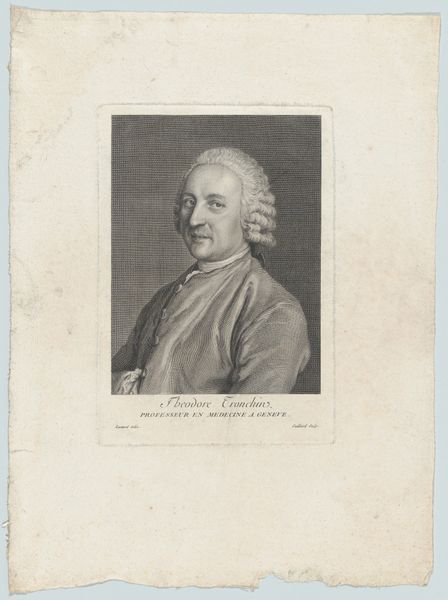

print, engraving

#

portrait

#

print photography

#

neoclacissism

# print

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 255 mm, width 184 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: Here we have "Portret van Christian Gottlob Heyne," an engraving made sometime between 1792 and 1816 by Johann Friedrich Wilhelm Müller. It resides here at the Rijksmuseum. It is such a powerful rendering. Editor: My first impression is the stark contrast. The way the light catches his face gives it almost a sculptural quality. I'm immediately drawn to the detail in the coat – you can almost feel the texture of the fabric through the engraving. Curator: Absolutely, the neo-classical movement definitely plays a huge part in this artwork, it presents the sitter with clarity and simplicity. We're seeing a deliberate attempt to link Heyne to the ideals of enlightenment. He appears serious and distinguished. Engravings like this were widely accessible, therefore circulating powerful portraits to broader audiences was more easily achievable. Editor: I find the means of production interesting in itself, though. Each line, each dot is carefully etched onto a metal plate before even creating an image on paper. The labor involved speaks of both the subject's importance and also how far a studio had come regarding print production, doesn’t it? Curator: Exactly! The choice of engraving wasn't arbitrary. Prints democratized art in many respects. Images like these bolstered the subjects reputation and made them into role models. Editor: Yet, there's something inherently tactile about the engraving process. You feel that connection to the hand that guided the burin. It bridges the gap between the artisanal and the industrialized. The labor certainly adds a different type of value. Curator: I agree that this tension between craftsmanship and mass production is central to understanding its impact at the time, and frankly, how we engage with it now. We can consider not only the image it projects of Heyne, but the conditions of its own making. Editor: Definitely! The history embedded within the materiality is pretty extraordinary here. The final work invites considering all its layers from materials used and labour implied, which are equally a testament to the image’s status. Curator: Considering that context, it is perhaps no longer a passive object of observation but an active agent in culture and society. It definitely broadens its reach for contemporary audiences. Editor: Indeed, by recognizing those material conditions we create access points into what it means. The historical narrative gains a very crucial perspective, doesn't it?

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.