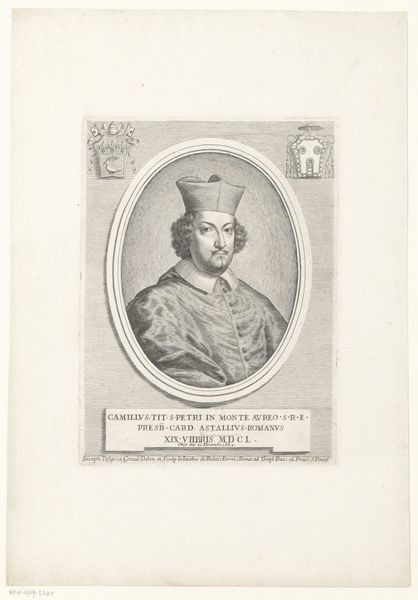

print, engraving

#

portrait

#

baroque

# print

#

history-painting

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 161 mm, width 121 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: Here we have Pieter de Jode the Younger's print, "Portrait of Philip III, King of Spain," likely made between 1628 and 1670, residing here at the Rijksmuseum. What's your immediate impression? Editor: Regal, but… weary. There’s a stiffness in his pose, almost as if the weight of the crown is a literal burden. The baroque frame feels a bit claustrophobic for such a powerful figure. Curator: Baroque portraiture often aimed to project power, connecting the subject to both earthly authority and divine right. The symbols, from the crown to his elaborate dress, communicate a very specific image. Philip III ruled during a period of great change and conflict, perhaps reflected in that perceived weariness. Editor: Absolutely, it is about constructed power. Notice the sceptre. It is elongated, thin, and very present, emphasizing that tangible authority, while the crown itself is intricately detailed, laden with familiar European symbols of royalty. But there is also an almost forlorn aspect with that architectural background. It could speak to Spain's global power at the time or also its limits. Curator: The setting—likely alluding to a palace—underscores his dominion. Remember that the historical context matters. This portrait circulates as propaganda, reifying the Spanish monarchy at a specific time when their overseas territories were crucial, with “Hispanarium et Indiarum Rex,” King of Spain and the Indies printed boldly. The baroque period in Spain saw a drive for consolidation amidst declining political power and influence across Europe. The prints would play a role in boosting the monarchical image at the time. Editor: You're right; even the framing participates. The arch feels like a stage, carefully presenting Philip. And notice how his gaze engages directly with the viewer, trying to establish this powerful contact that might be compensating for some internal and external tensions, which are not necessarily visually manifested otherwise. Curator: I agree. And it reveals that prints such as this weren't just art objects, they were critical tools in shaping political and cultural perceptions during the period. Editor: Ultimately, a very evocative piece, prompting us to reflect on not only the visual symbolism but also the broader social and political function of imagery in its era. Curator: Indeed, revealing a multi-layered understanding of power, representation, and the enduring legacy of political art.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.