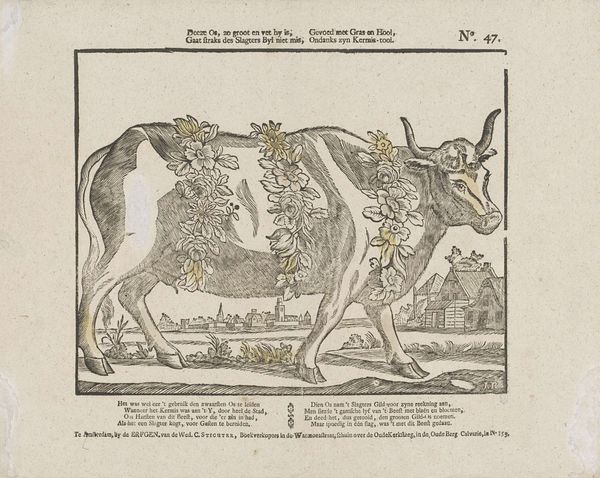

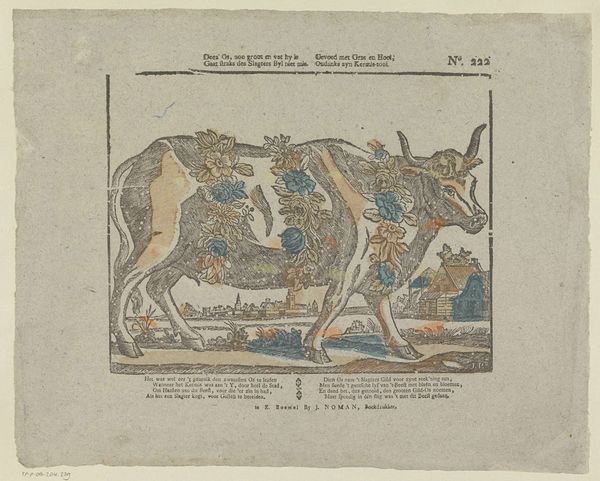

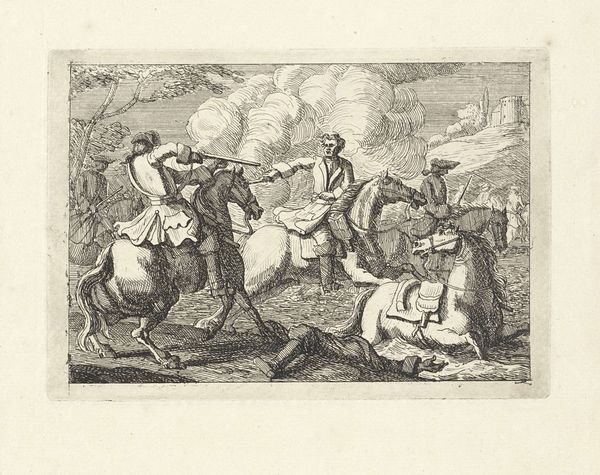

Deeze os, zo groot en vet hy is, / Gaat straks des slagters byl niet mis, / Gevoed met gras en hooi, / Ondanks zyn kermis-tooi 1715 - 1813

0:00

0:00

ervenweduwecornelisstichter

Rijksmuseum

Dimensions: height 305 mm, width 410 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: This is a delightful, slightly macabre engraving from the period between 1715 and 1813, housed in the Rijksmuseum. The full title, written in Dutch, is "Deeze os, zo groot en vet hy is, / Gaat straks des slagters byl niet mis, / Gevoed met gras en hooi, / Ondanks zyn kermis-tooi". It translates roughly to "This ox, so big and fat, will soon meet the butcher's axe, fed on grass and hay, despite its carnival dress". Editor: Carnival dress! My first impression is definitely bittersweet. There's a charming naiveté in the rendering, the folk-art style almost, but the poem hints at a very different reality – the impending slaughter. Curator: Absolutely. Context is key here. Consider the time this image was created; agrarian societies had a very different relationship with livestock and butchery. The ox, adorned with flowers for what we might assume is a market day parade, is literally being fattened for the kill. It's an accepted part of life. Editor: Right, and seeing those blossoms set against the ox's bulk invites reflections on societal power structures. The decoration feels like a superficial attempt to mask the ox’s inevitable fate – mirroring how celebratory rituals are often used to gloss over brutal realities. What readings can we get from the setting and landscapes included? Curator: Good point! The detailed backgrounds, city and ruralscapes that sandwich the animal between the community are vital elements to highlight; one side shows where its work will benefit inhabitants. But conversely there is the more serene countryside where the animal has enjoyed simpler days, but the artist makes clear it's not forever. Editor: It brings to mind questions of labor exploitation, and our relationship with natural resources. It’s such a seemingly simple image, but resonates so deeply with modern intersectional concerns around class, environmentalism, and capitalist structures. How are celebratory cultural references connected here to food consumption? Curator: Indeed. Consider the artist's technique: the rather simple lines are juxtaposed with great visual commentary. A look at a working community as the ox gets taken for slaughter and sustenance is interesting. I find this particularly powerful given that prints were, at this time, an increasingly accessible art form for ordinary people. It raises all these social ideas right under your noses in simple ways. Editor: It's interesting how seemingly innocent folk-art can hold such complex, critical social messaging when examined under historical and contemporary lenses. This work invites crucial dialogue on who benefits and who gets sacrificed in broader socio-economic narratives. Curator: Precisely. It's a potent reminder that even in art depicting the seemingly mundane, there are profound reflections of power, politics, and identity awaiting our deeper consideration.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.