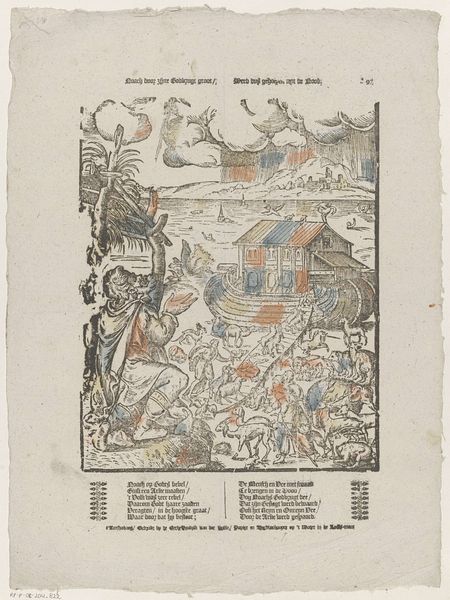

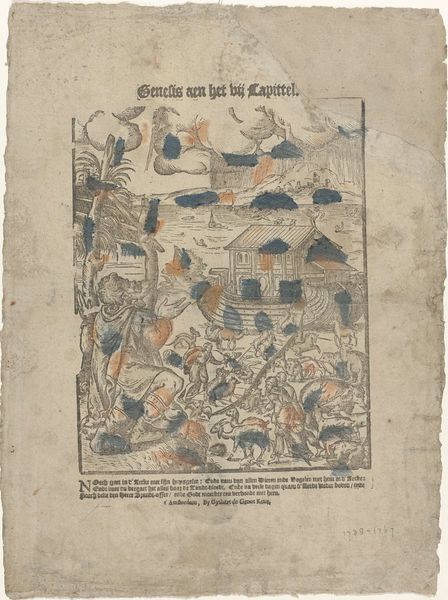

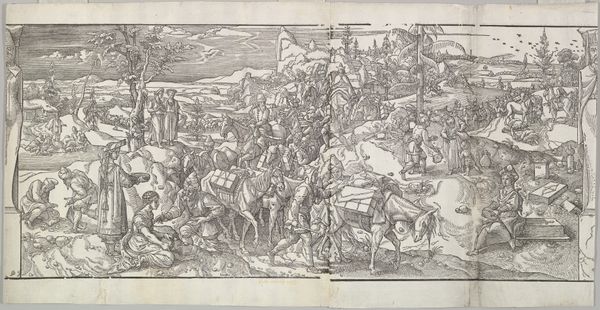

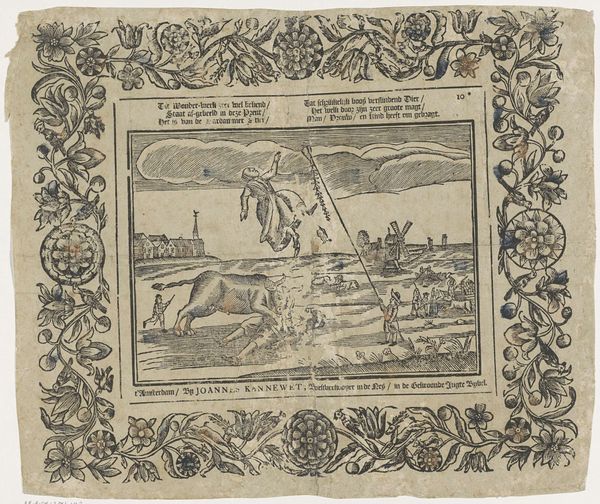

Noach door zijne Godsvrugt groot / Werd dus geholpen uyt de Nood 1767 - 1793

0:00

0:00

ervenhendrikvanderputte

Rijksmuseum

Dimensions: height 413 mm, width 315 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: The piece we're looking at is an engraving from between 1767 and 1793 titled, "Noach door zijne Godsvrugt groot / Werd dus geholpen uyt de Nood." Which, loosely translated, means "Noah, great through his Godliness, Was Thus Helped out of Need." A bit wordy, isn’t it? Editor: Immediately, I’m struck by its dreamlike quality. It's like a medieval tapestry rendered in delicate lines. The whole scene feels very staged and carefully composed, with all these animals trooping along towards the ark. It almost makes the Great Flood look quaint, a charming, even pleasant journey rather than utter devastation. Curator: It’s definitely baroque in its busyness, that urge to fill every single space! The artist, who remains unknown unfortunately, used this really fine line work to create depth and texture. Look how the animals are all rendered individually, each little fur and feather accounted for. It’s incredibly detailed. Editor: That detail almost serves to depoliticize it, don't you think? We lose the sheer horror of the event, the scale of the environmental disaster, the injustice of it all. Instead, we get this carefully managed procession, as though nature is following human directive instead of nature violently reclaiming what was already theirs. Where's the fury in that water? Where is the agony of creation? Curator: It’s interesting you say that. For me, this artist clearly sought to communicate Noah's piety and God's divine intervention. The ark is obviously the main focus, brightly illuminated, safe haven in a chaotic world. What’s key to note, of course, is the power of devotion, which has perhaps overshadowed the political aspects you have referenced. Editor: But shouldn't art reflect reality, even a fantastical reality? This feels too… sanitized, too safe. Where is the critical perspective, the call to social justice, the inherent acknowledgement of trauma? It all makes you consider the privilege afforded by religious narratives to ignore some crucial conversations surrounding disaster. Curator: Perhaps the artist just wasn't aware of those concerns when creating the work! Maybe it reflects the culture where questioning the literal interpretation wasn't considered…ahem…neighborly. I personally value seeing older artistic traditions recontextualized as historical markers. Editor: I guess this print does force a necessary juxtaposition—an encounter between traditional narratives and current realities, but ultimately, it comes across as disconnected. Curator: Yes, I suppose at the end of it all, a fresh viewpoint can highlight limitations but maybe even strengths we never saw at first glance. Editor: Definitely a reminder that art can often echo societal norms or contest those exact beliefs, isn't it?

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.