photography

#

portrait

#

caricature

#

photography

#

historical photography

#

19th century

#

portrait art

#

realism

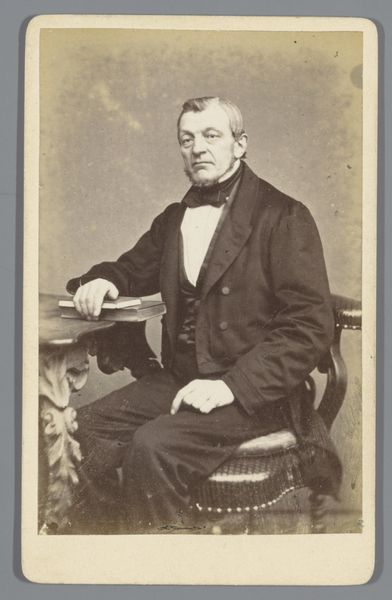

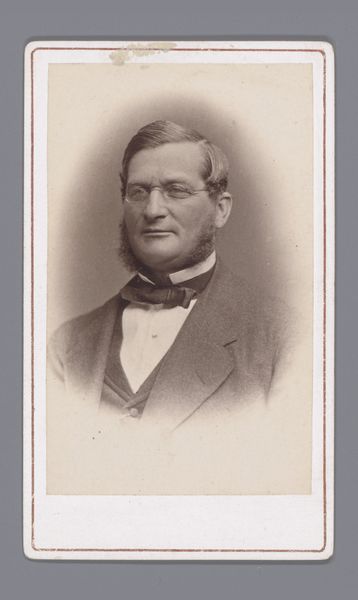

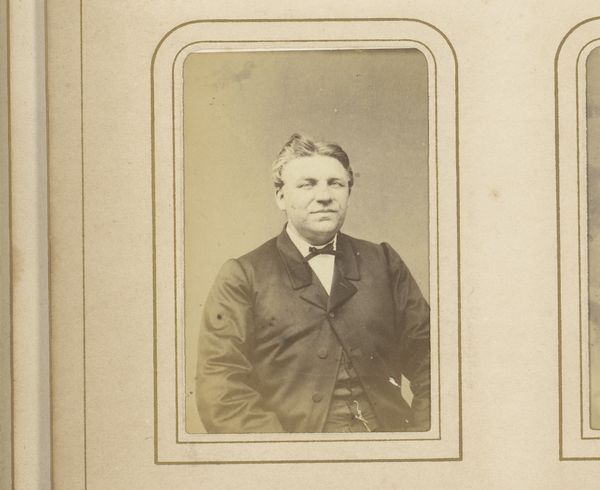

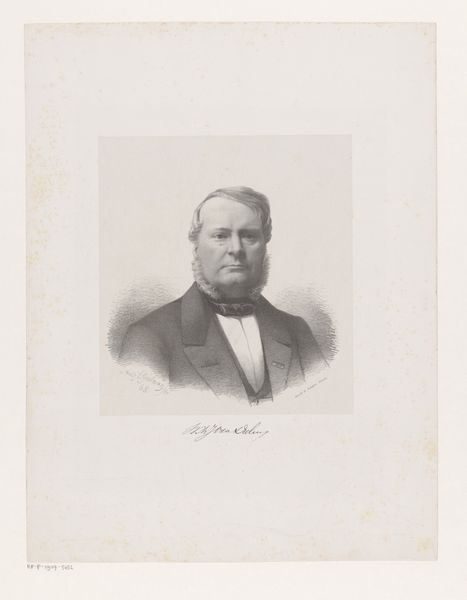

Dimensions: height 140 mm, width 96 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

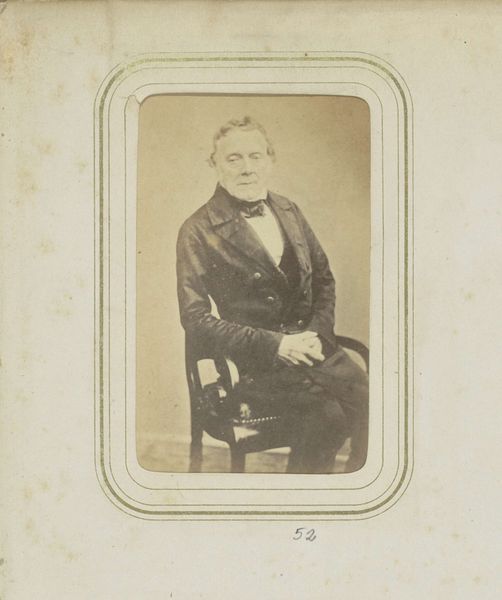

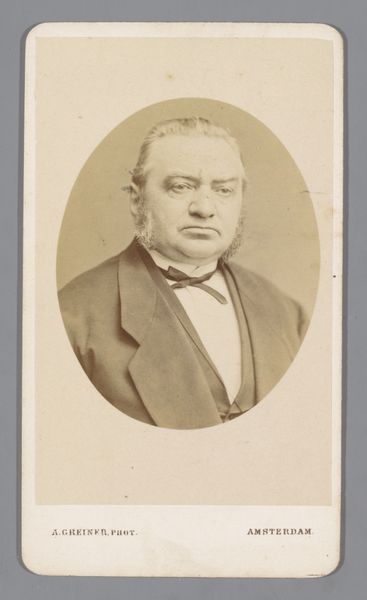

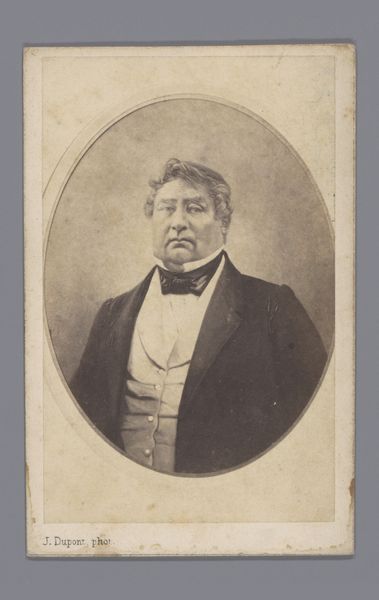

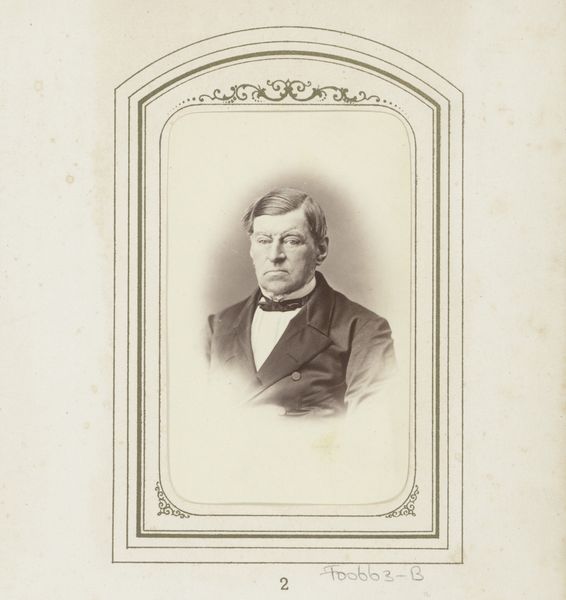

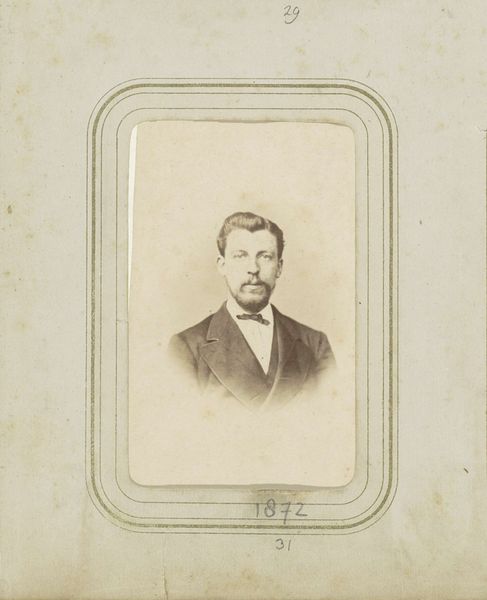

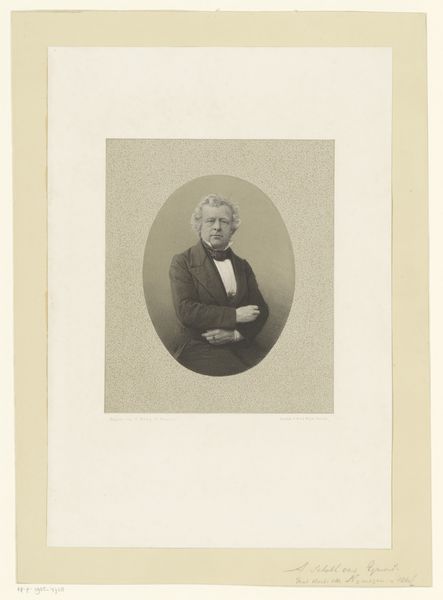

Curator: Before us we have a photograph, "Portret van een man met vlinderstrik"—Portrait of a Man with Bowtie—attributed to Charles Binger, created sometime between 1872 and 1887. It's a rather conventional piece, wouldn't you say? Editor: Oh, conventional perhaps, in its framing. But the instant my eyes land on him, I see this incredible stoicism… like he's seen empires rise and crumble, all while holding onto that tiny, defiant bowtie! It feels very personal, very raw. Curator: Personal, certainly, for the sitter and possibly for Binger, the photographer, if he had any rapport. The subject fills the frame, constrained by an oval border which adds a layer of visual compression to the photographic plate. The composition centres entirely on the man’s features, rendered with clarity given the era’s technological limitations. The dark, somewhat brooding palette, creates an imposing sense of formality and controlled dignity typical of bourgeois portraiture. Editor: Yes! Brooding! Like he holds a secret—or a subtle disapproval of… us. He’s very real, his slightly asymmetrical features, his weary eyes, tell a story that transcends the formal conventions. It’s interesting that even within the constraints of formal portraiture the emotional life is so compelling. Curator: You speak of his realness. This realism stems from the contrastive and somewhat unforgiving detail only rendered via the then newly harnessed process of capturing an individual likeness via photochemical means, though as a ‘portrait’ its realism is merely performative. This form reflects very specific social functions which is where it derives it's core cultural meaning. This particular photograph, with its sombre tones and clear details, shows us this man within the very definite cultural structures of late 19th century bourgeois society. The bowtie, of course, as both symbolic and material. Editor: I'm so moved by what a little square of cloth says about the guy… It makes you wonder: What did a day in the life look like for this man? I am certain it was not easy… But now I just want to give him a pat on the back. Curator: Indeed, that’s the power, perhaps even danger, of representation! It invites narrative speculation. So, through our close encounter we can take this study of tonal contrast, texture, and composition—an aesthetic artifact if you will—and then, through our combined responses we humanize its story. Editor: Exactly! That image is a looking glass where form meets feeling. That’s how photographs still manage to haunt and move us, right?

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.