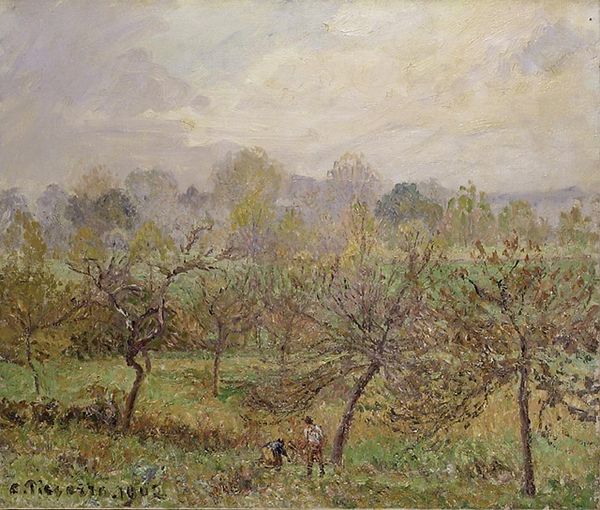

Copyright: Public domain

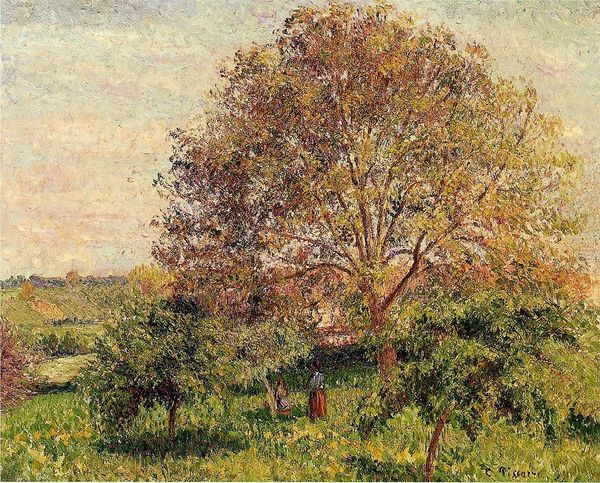

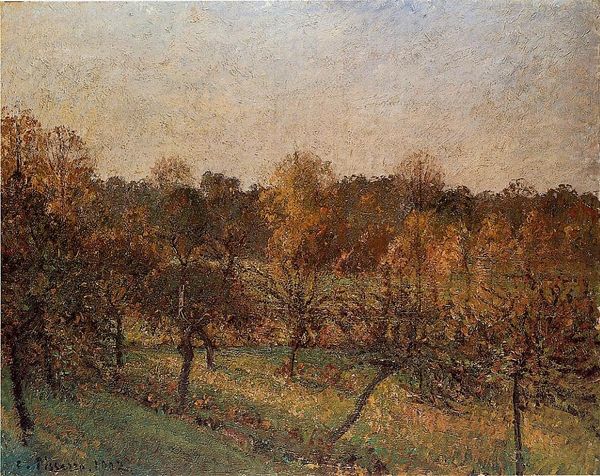

Editor: This is Camille Pissarro’s “After the Rain, Autumn, Eragny,” painted in 1901. It’s an oil painting depicting a landscape. It feels very… soft, somehow. The colors are muted, and it gives me a sense of quiet observation. How do you interpret this work? Curator: What I see here is more than just a peaceful landscape; it’s a potent reminder of the often-overlooked labor embedded in the rural. Pissarro, unlike some of his Impressionist contemporaries, consistently included working-class figures in his landscapes. Do you notice the figures and perhaps a donkey in the middle-ground there? Editor: I do, now that you mention it! They almost blend into the background, though. Curator: Precisely. Pissarro positions them within the landscape to prompt questions about their relationship to the land itself. How is their labor shaping the landscape, and vice versa? We should ask, Whose story is being told when we sanitize or romanticize landscape painting by excising labor? This particular view, painted from a slightly elevated perspective within his garden, can even invite considerations about land ownership. Who gets to view the land in comfort? Editor: That's a completely different way of looking at it. I was just thinking about the pretty colors! Curator: I want to stress, these quiet observations also speak to Pissarro’s radical politics, his anarchism and commitment to social justice, which were deliberately woven into his art. His artistic choices – from subject matter to technique – reflected his desire to give visibility to those rendered invisible by the dominant social order. Editor: So, even an Impressionist landscape can be a form of social commentary. That’s fascinating! Thanks, I never would have seen that on my own. Curator: Exactly! And it's these intersectional readings that reveal the power art has to critique and reshape our understanding of the world.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.