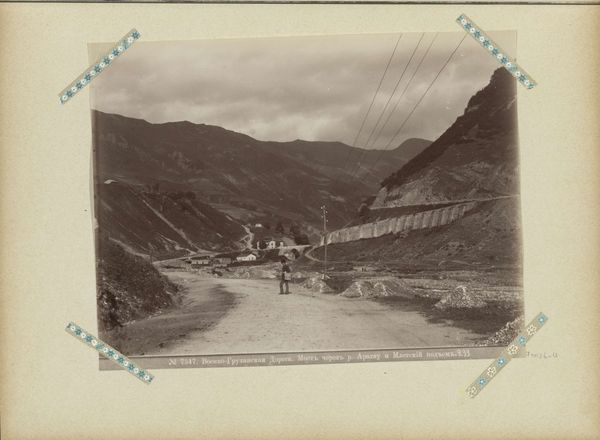

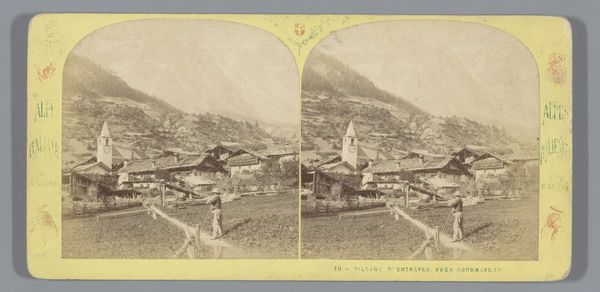

photography, gelatin-silver-print, albumen-print

#

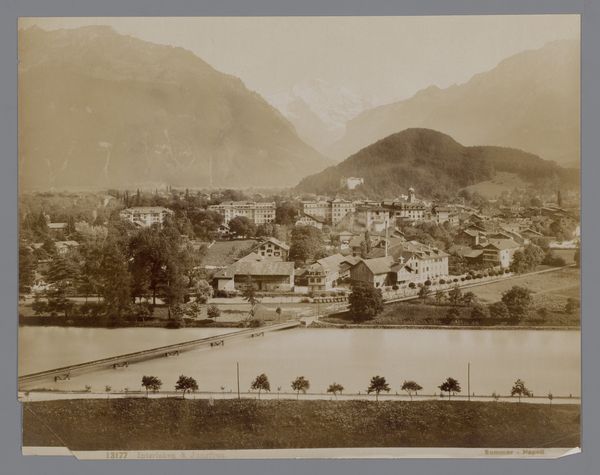

landscape

#

river

#

photography

#

gelatin-silver-print

#

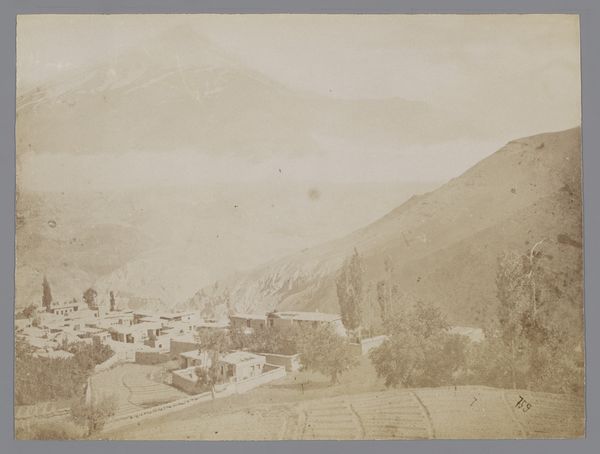

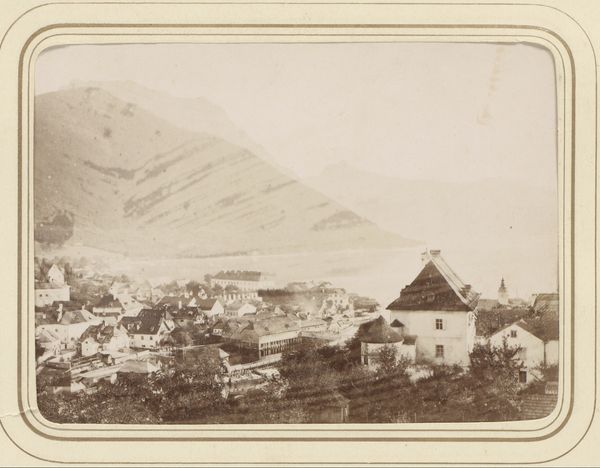

cityscape

#

albumen-print

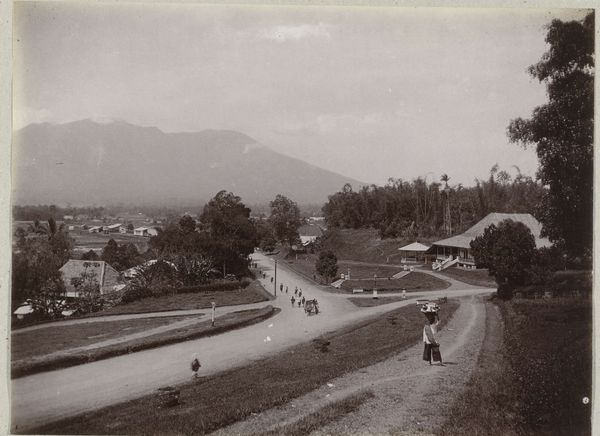

Dimensions: height 119 mm, width 186 mm, height 315 mm, width 421 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: This is "Vallei van de Borrigo, Menton," a photograph attributed to Neurdein Frères, dating from around 1863 to 1891. It's a gelatin-silver print, or perhaps an albumen print, capturing a townscape in muted sepia tones. Editor: My immediate reaction is one of stillness, even desolation. The scene feels emptied, almost as if the image is documenting a collective retreat from this space. Curator: The stillness certainly permeates. Considering its historical context, I find that the landscape carries potent symbolism. Water, typically a symbol of life and renewal, is channeled and seemingly devoid of its vital essence, perhaps reflecting anxieties about resource management and control, certainly about how cities change the landscape. Editor: The materiality itself amplifies this sense. The gelatin-silver process would have involved careful labor, manipulating light and chemicals to capture and fix this moment. The flatness almost abstracts the social implications: the stark contrast of raw land near constructed buildings—and who benefitted? Curator: It speaks volumes about how we visually encode anxieties, reflecting not just a literal space but also the psychological and social landscapes of the era. Notice how the distant structures atop the hill dominate—they function as symbols of established power, overlooking the community and reinforcing ideas of hierarchy and order. Editor: Right, and this reinforces my instinct to examine the physical means through which such hierarchies were materialized. Photography, with its mechanical objectivity, became complicit in defining a world ordered around industry and class, framing even natural landscapes as subjects ripe for measurement and extraction. Look at that controlled water— Curator: But perhaps this ‘objectivity’ also unwittingly exposes the rifts, laying bare the environmental impact and implicitly asking the viewer to consider what’s lost in this pursuit of progress. Editor: Possibly. But this loss is muted, romanticized, as a shadow in an artifact. I wish we had context on their darkroom and their access to material—were they wealthy landowners who felt detached enough to see their domain as an aesthetic object? Curator: It makes me rethink how the symbolism plays. While the photo offers a sense of a physical location, it perhaps unintentionally acts as a mirror to internal human dilemmas—about our interventions and the narratives we spin around progress, even if only for an elite viewership at the time. Editor: Looking at this photographic print then, it serves as an entry point to broader conversations—not only about representation and the power of images, but also about our evolving relationship with material reality, both natural and built.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.