daguerreotype, photography

#

portrait

#

16_19th-century

#

daguerreotype

#

photography

#

romanticism

#

realism

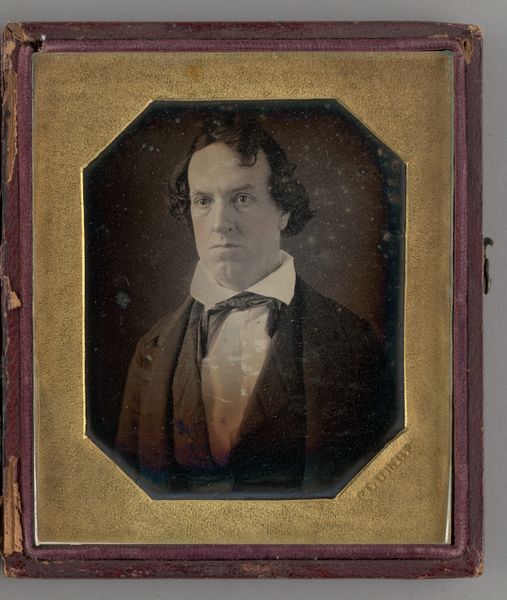

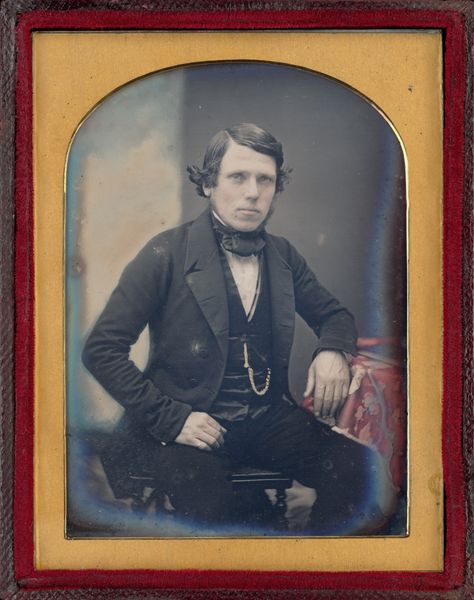

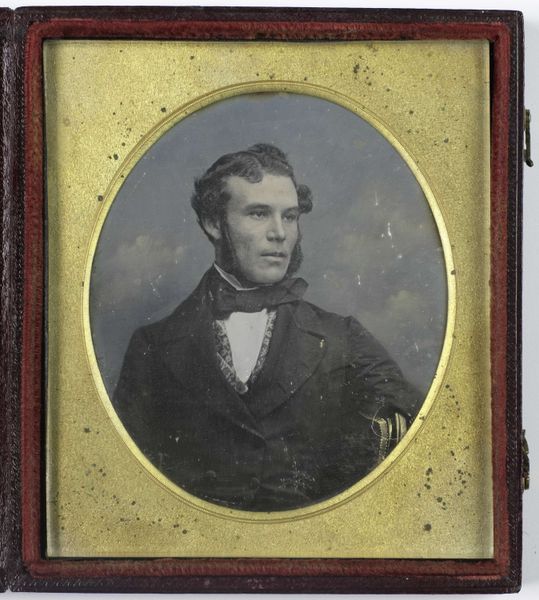

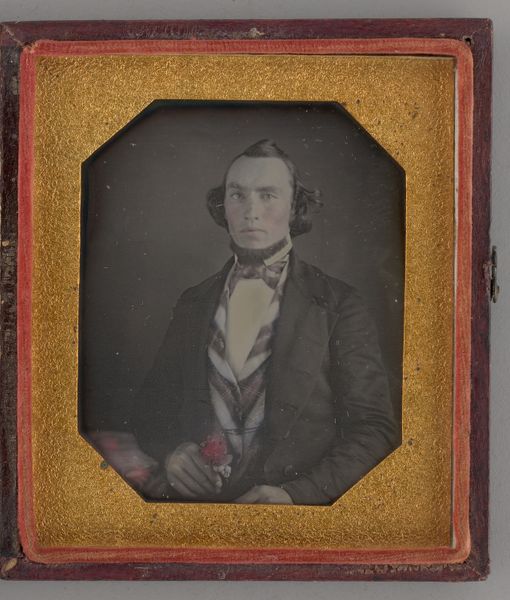

Dimensions: 10.7 × 8.1 cm (4 1/4 × 3 1/4 in., plate); 12 × 18.6 × 1.1 cm (open case); 12 × 9.3 × 1.9 cm (case)

Copyright: Public Domain

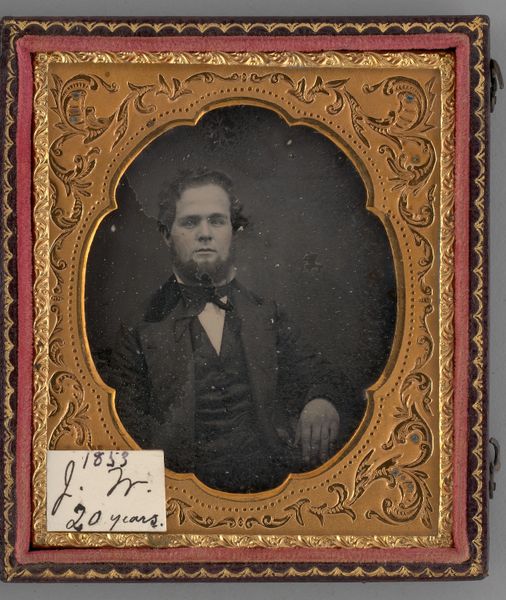

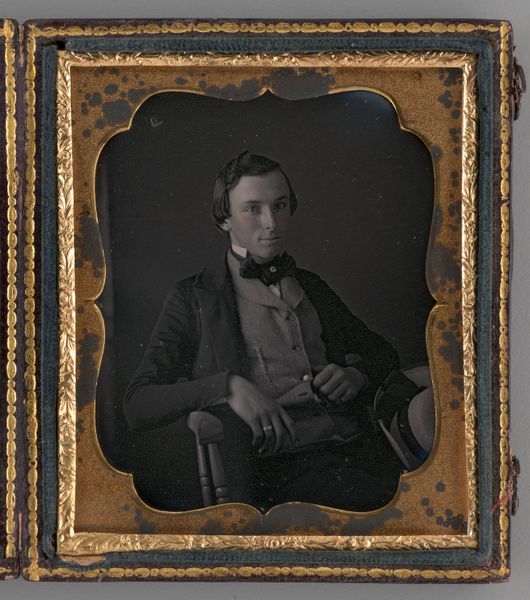

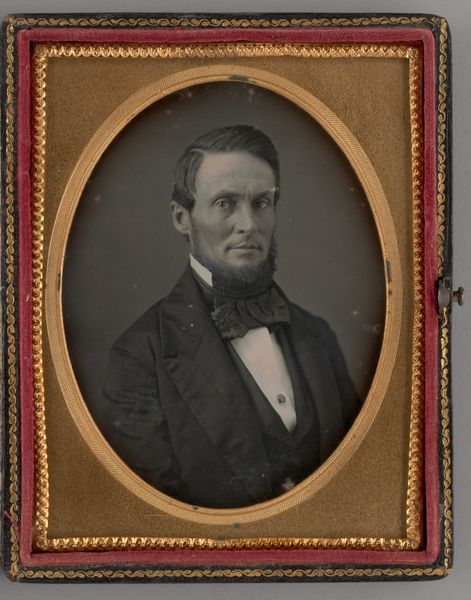

Curator: Here we have an intriguing piece from 1848, "Untitled (Portrait of a Man)", housed right here at the Art Institute of Chicago. It's an early example of photography, a daguerreotype. Editor: My first thought is how remarkably modern he looks, despite the historical trappings. There's a quiet intensity in his gaze. You can almost feel the weight of the materials involved – the glass, the metal, the chemicals all combining to capture this fleeting moment. Curator: Precisely. The daguerreotype was groundbreaking, democratizing portraiture to some extent. Suddenly, the burgeoning middle class had access to images of themselves, participating in constructing their public identity. Editor: And what a material statement it is. Silver-plated copper, meticulously polished. Think of the labor involved, both in creating the plate and in sitting for the exposure. This wasn't a quick snapshot; it was a crafted object, signifying status. Curator: True, although early photography still carried a hefty price tag, ensuring its association with status. However, compare it to the painted portraits that preceded it! It was far more accessible to broader segments of society. It created new markets, new social expectations about how we record ourselves and others. Editor: That handcrafted nature really emphasizes its connection to the artisanal. It disrupts this traditional hierarchy, doesn’t it? It places a process of mechanical and chemical work next to other traditionally accepted art-making processes. And look closely, you can still discern minor imperfections, subtle blemishes in the silver, evidence of the hand at work, humanizing the image. Curator: Absolutely. Even these perceived "imperfections" lend authenticity. It’s fascinating to consider this portrait in the context of evolving 19th-century social and political forces. The daguerreotype served as a vital instrument, constructing a national visual archive of its citizens and influencing narratives of identity. Editor: I appreciate the image all the more, recognizing how its material construction directly connects it to both social shifts and artistic endeavors. It really prompts consideration of how much has changed about image-making, and how much hasn’t. Curator: I find myself seeing his portrait as a powerful example of how shifts in technology shape societal perceptions of identity and memorialization.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.