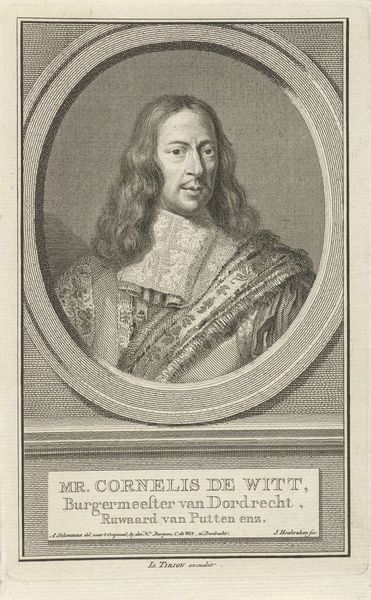

print, engraving

#

portrait

#

baroque

# print

#

old engraving style

#

history-painting

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 265 mm, width 180 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: Looking at this engraved portrait of Charles I, made by Bernard Picart in 1729, we can really appreciate the detailed rendering of his garments. Editor: Indeed! The textures created solely through engraving are remarkable. What exactly strikes you as you examine the process here? Curator: It's important to consider what engraving *means* in this context. Prints like these, especially portraits, served as reproducible markers of power and status. This engraving makes those markers, initially belonging to a King, broadly accessible for a very low price. The choice of clothing—that intricate lace collar, the elaborate cloak—are as much about social positioning as they are aesthetic details, made accessible for a small price to the middle class. Picart essentially commodified an image of monarchy through reproductive technology. Consider the division of labour; who was designing these garments? Where did the lace originate, and under what conditions? It all speaks volumes about material culture and its translation across artistic mediums. Editor: So, you're saying that it's less about the artistry of the portrait itself and more about its function as a manufactured item meant to represent royal power, in a reproducible form, making that royal identity more available to more people? Curator: Exactly. The "art" isn’t just in Picart's skill with the burin, but in the whole socio-economic process that makes such an image possible and necessary. Editor: I never thought about the making of art in such social terms before. It adds a whole new dimension to understanding its impact! Curator: Right, seeing the web of labor woven into each piece provides a whole other view.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.