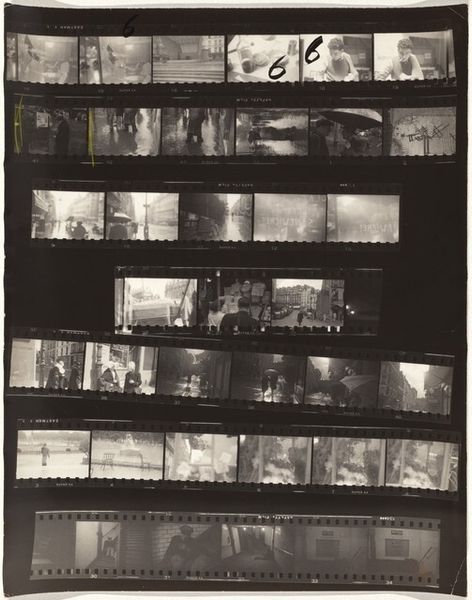

photography, gelatin-silver-print

#

portrait

#

dark object

#

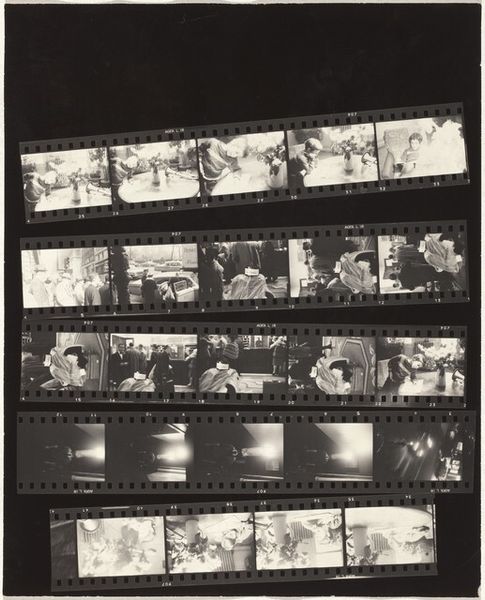

wedding photograph

#

wedding photography

#

dark hue

#

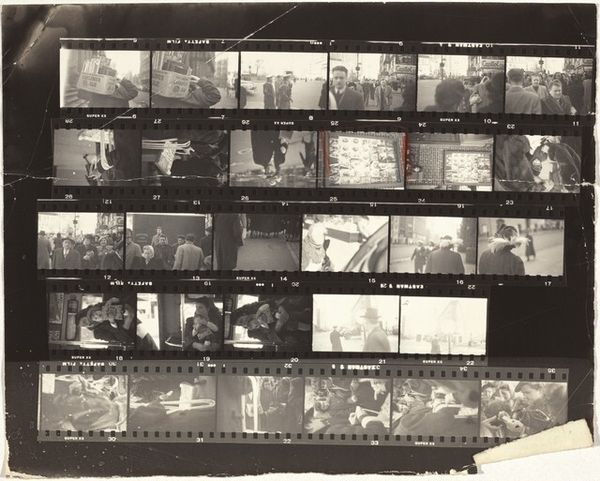

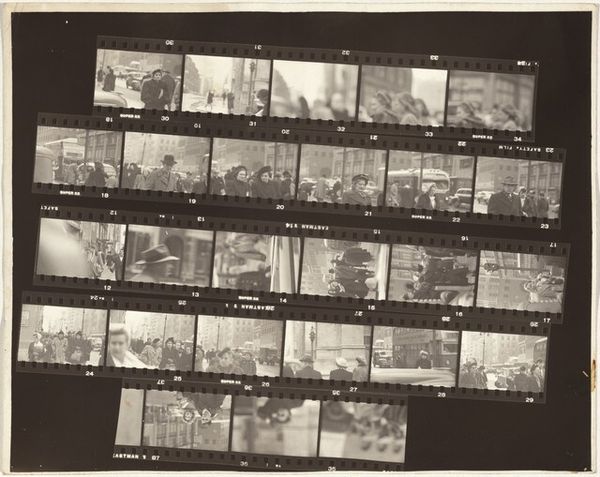

street-photography

#

dark monochromatic

#

photography

#

black colour

#

dark shape

#

repetition of black colour

#

gelatin-silver-print

#

monochrome photography

#

black object

#

cityscape

#

monochrome

Dimensions: sheet: 25.2 x 20.2 cm (9 15/16 x 7 15/16 in.)

Copyright: National Gallery of Art: CC0 1.0

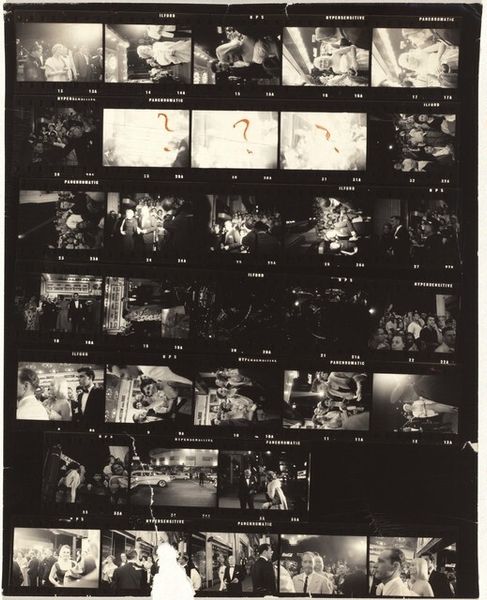

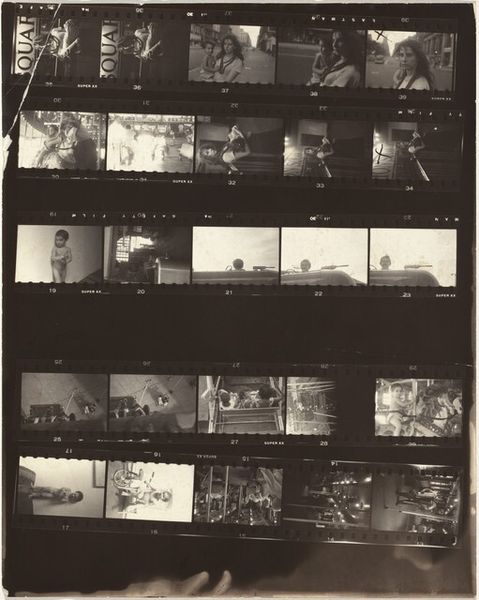

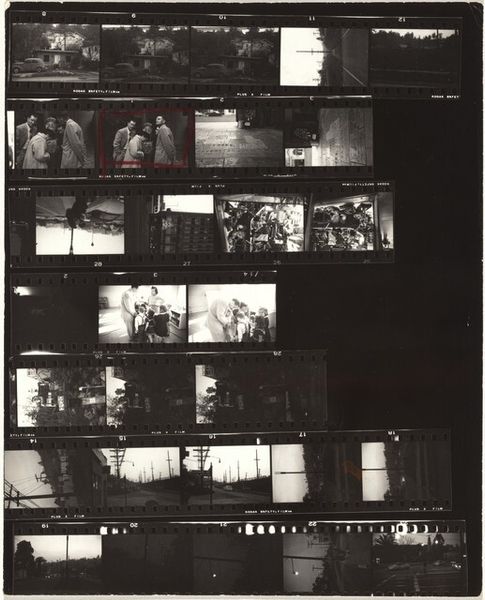

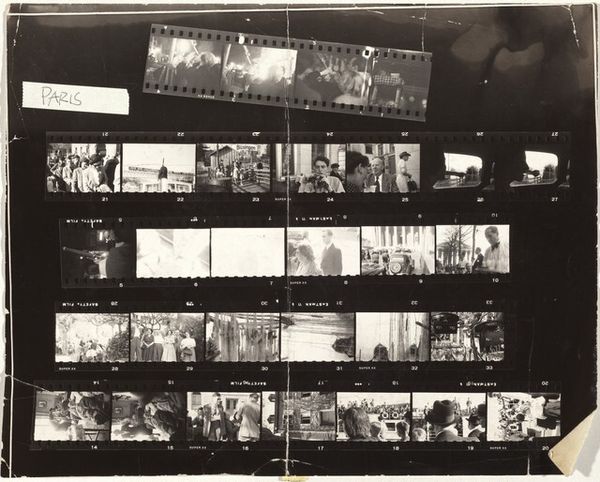

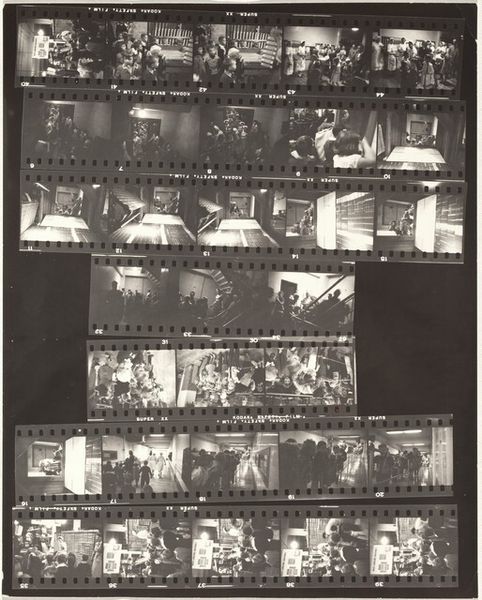

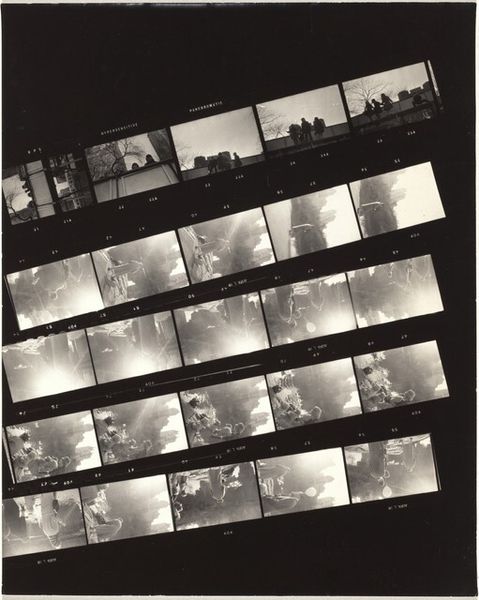

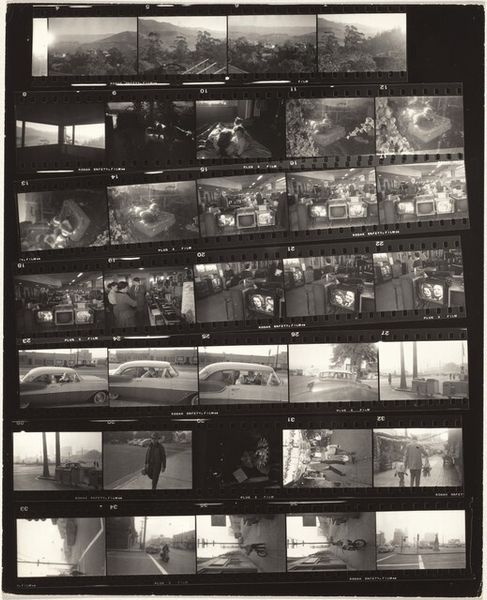

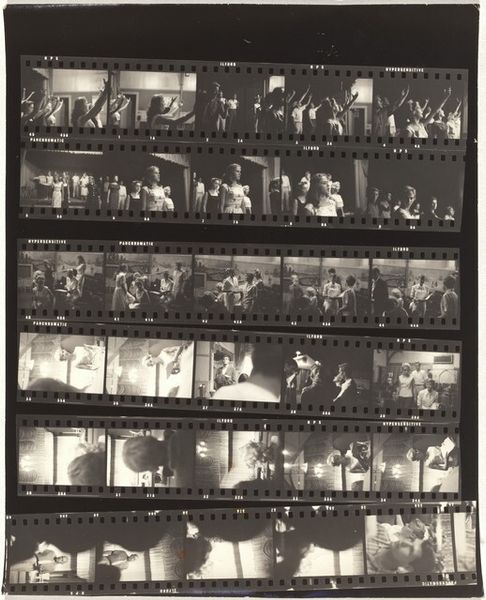

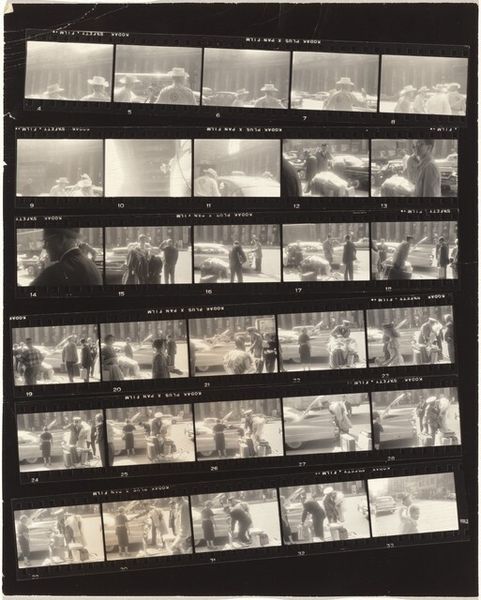

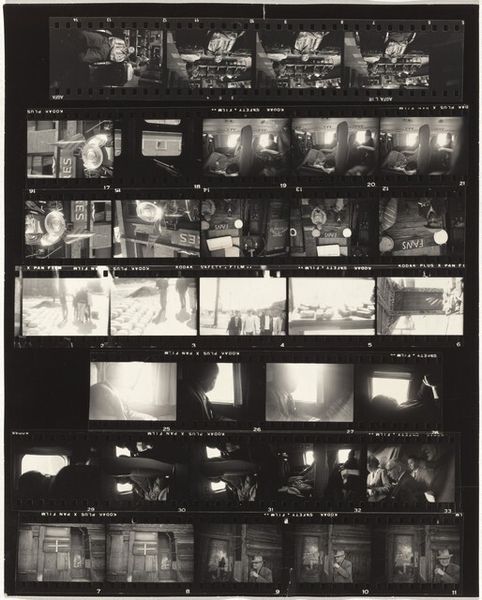

Curator: This gelatin silver print, made by Robert Frank around 1957 or 1958, is titled "New York Times" ideas no number. What strikes you initially about this work? Editor: The immediate effect is its fragmented nature, resembling filmstrips pieced together. There's a darkness, a sense of urban grit permeating the whole thing. Curator: Indeed. Frank was very intentional in his depiction of post-war America, and he often focused on the darker undercurrents. Here, the choice of a "New York Times" headline hints at a societal commentary—a reflection on ideas, but through a lens of fractured reality. Think about the power structures at play and what a title such as this is hoping to convey. Editor: And that fragmentary feel aligns with a kind of modern alienation. You see glimpses of different scenes - a city street, an interior with people dining – as if randomly stitched together. I’m immediately wondering how that physical creation process mirrored or challenged what he was seeing in those scenes. What was his darkroom process for arriving at this image? Curator: His working process mirrors the disjointed feeling of the image. Frank intentionally moved away from traditional notions of photographic perfection, embracing blur and unconventional compositions. The gelatin silver print underscores that material presence—that tangible object. Editor: I’m curious about the labor of taking all of the photos. Was it mass production intended for commercial goals, or a project with a finer hand that intentionally undermined consumption or mass-media? Curator: The selection of images—a seemingly mundane snapshot of dining, juxtaposed with cars and what appears to be gallery scene, all filtered through a dark filter, seems almost as a metaphor for art world elitism of the period. Editor: I see how Frank used these mass production photographs, but made deliberate choices in how they were shot and composed that were not straightforward. They don’t celebrate commercialism, they interrogate it through this arrangement and printing. It really complicates our relationship with the image and the objects/materials displayed in each picture. Curator: I completely agree. Frank’s art compels us to ask who has the power to curate narratives, and who gets left out of the frame. Editor: So while each fragment contains its own labor, when printed together, they show that the photograph, as a product and form of visual labor, still has a grip on us today. Curator: That's insightful. It encourages us to deconstruct dominant narratives. Editor: And that is how the photograph continues to endure, if not thrive today.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.