Dimensions: height 138 mm, width 110 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

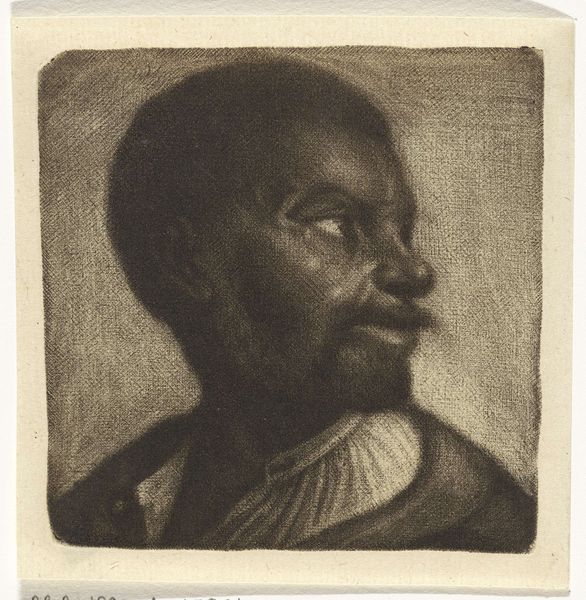

Curator: Here we have Louis Bernard Coclers' "Portret van een Abessiniër," an engraving from around 1756-1817. It depicts an Abyssinian man in profile. Editor: It's fascinating how the artist captured the texture and details using only engraving. The man’s gaze is quite intense. How can we interpret this portrait from a materialist point of view? Curator: Focus on the labor involved in producing this print, which in turn facilitated consumption, a representation and a performance of power dynamics. Coclers meticulously carved these lines, a process that required both skill and time. Engravings like this were not just art objects, they were commodities, intended for distribution and exchange. Editor: So the very act of creating and circulating this image is part of the story? Curator: Precisely. Who was commissioning these portraits, and why? Who had access to them? What image of the depicted subject does this work reflect? We should ask how the means of production – engraving – shaped the consumption and, by extension, the social perception of race and exoticism during that era. Editor: It’s a powerful medium, considering its ability to disseminate images widely, especially when painting could only be displayed in a limited space for specific audiences. How would the process and labor that went into this affect its meaning? Curator: The print's materiality and mode of production allows a far greater and wider audience to consume the exoticized ‘other,’ thus creating and maintaining biased concepts and values within society. Understanding the social and economic context is essential. Editor: I never thought of it that way. Viewing it through this perspective adds such depth and historical awareness to understanding the art. Curator: Indeed. Focusing on material and social elements often unlocks a different layer of the narrative.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.