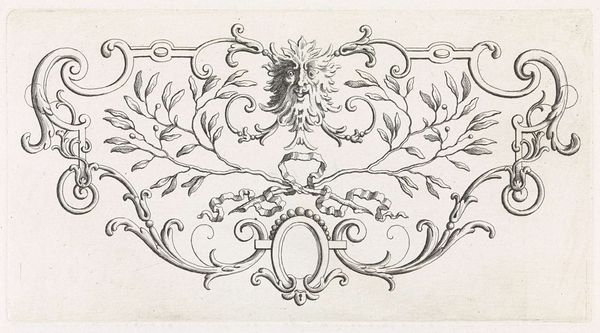

ornament, print, engraving

ornament

baroque

geometric

line

decorative-art

engraving

Dimensions: height 135 mm, width 160 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Editor: This engraving, "Leeuwenkop tussen twee gekrulde slangen" created between 1573 and 1610 by Christoph Jamnitzer, presents a striking lion's head intertwined with coiled snakes. The linework is incredibly detailed, and I'm curious about its function as an ornament. What do you see when you look at this piece? Curator: I see a fascinating example of the intersection of art, craft, and social status in the late 16th and early 17th centuries. We need to think about the means of production here. Engravings like this weren't just art objects; they were tools, weren’t they? Editor: Tools? How so? Curator: Exactly. Think about the labor involved: the engraver meticulously carving the design into a plate, enabling the mass production of these images. These prints facilitated the spread of design ideas and were essentially pattern books for artisans creating luxury goods. Editor: So it’s not necessarily “high art” then, but more like a design template? Curator: Precisely! It challenges the traditional boundaries of high art, blurring the lines between artistic expression and the decorative arts. And we need to think about who these artisans were, the systems of patronage and workshop practices that shaped their lives, and the market that consumed these ornate goods. The Baroque style, evident in its swirling lines and decorative complexity, reflects a period of both religious intensity and burgeoning global trade. Editor: It's fascinating to consider the print not just as an image, but as a product of labor, contributing to a wider network of artistic production. It’s design as industry, in a way. Curator: Yes! Thinking about the print’s material context offers a deeper understanding of its role within the social fabric of its time. That kind of informs how we value design, even today.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.