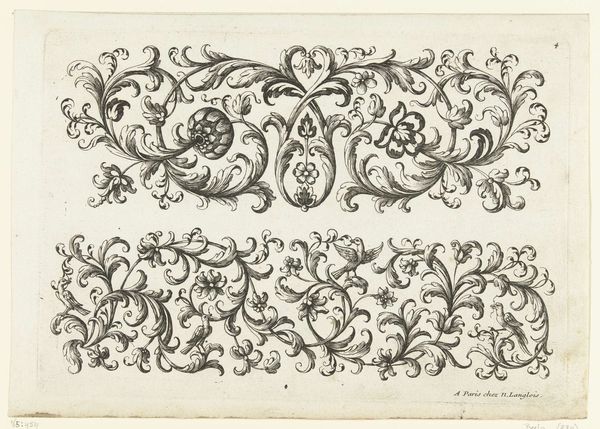

drawing, print, ink, engraving

#

drawing

#

baroque

#

pen drawing

# print

#

pen illustration

#

form

#

ink line art

#

ink

#

geometric

#

line

#

decorative-art

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 152 mm, width 239 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: Look at these extravagant flourishes. This print, titled "Twee friezen met bladranken"—or "Two Friezes with Leaf Tendrils"—dates back to the late 17th century, around 1670 to 1685. It’s currently held at the Rijksmuseum, and was made by Paul Androuet Ducerceau, a prolific figure in decorative arts. Editor: My initial impression is how ornate yet…controlled it feels? There's a tension between the organic forms and this almost mathematical precision. Like nature forced into geometry. Curator: Ducerceau was designing decorative elements for architects and craftsmen. These aren’t just random doodles; they were intended to be translated into physical structures, so the precision you note is vital. He needed to capture a certain reproducibility in the design to get the craftsman going in the right way. Editor: So, what socio-political role does decorative art play here? Was this a democratization of aesthetics, allowing more folks to implement design into their space or maybe further entrench class difference? You know, this could represent how Baroque art reinforced existing hierarchies through sheer opulence. Curator: Well, it does both, I think. The prints themselves made design ideas more accessible, yes. And Ducerceau was key in popularizing the Baroque style in architectural ornamentation beyond royal patronage. But those who implemented the design needed to buy resources and commission the craftsmen. A design like this might indicate taste, affluence, the leisure time to contemplate a decorative program for one’s home, perhaps? The image flirts with many things simultaneously: naturalism and abstraction. Editor: The geometric elements—that central triangle especially—feel very deliberate, like a symbol anchoring all that visual excess, perhaps referencing power structures...or maybe alluding to occult symbols popular during that era, eh? Curator: It’s funny, isn’t it, how easily we jump to conspiracy! I think it’s equally plausible it's simply an aesthetically pleasing shape offering a counterbalance to the swirling organic patterns surrounding it. I tend to like focusing more on Ducerceau as a facilitator here, passing his skill to many artists downstream. Editor: I find that notion very appealing, as well, the image can then become less about rigid declarations of power, and more about artistic collaboration as a mode of engagement with visual pleasure. It serves as an active agent in broader, decentralized creative contexts. Curator: Ultimately, what I love about this print is how it captures the energy of a specific era, and transmits these wild arabesques, for us to interpret. And it prompts us to think about the complex ways art engages in design, class, power, and even pleasure. Editor: And that's a reminder that art never exists in a vacuum—it’s always a reflection of the society that produced it, right? The act of noticing, is never simply looking.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.