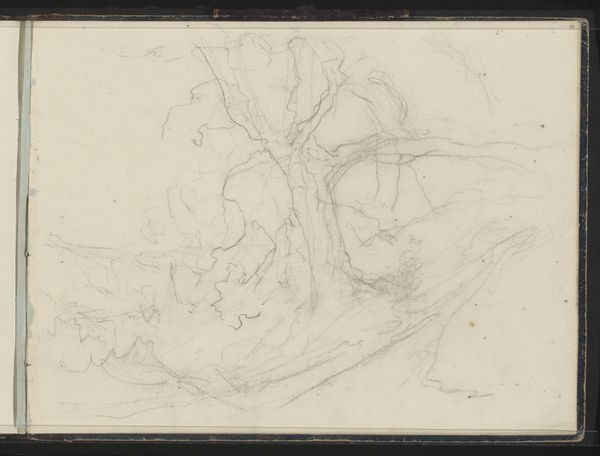

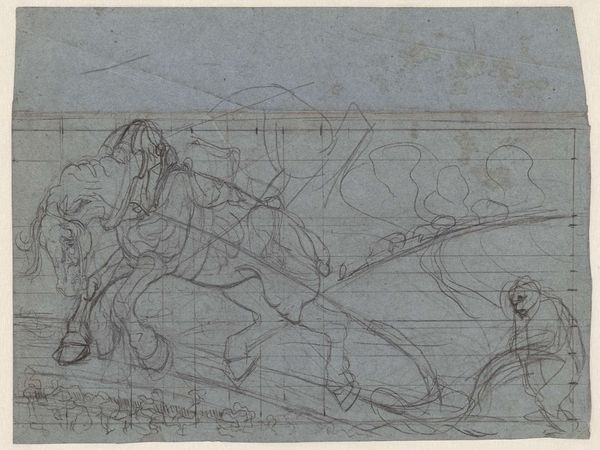

drawing, paper, pencil

#

drawing

#

impressionism

#

landscape

#

paper

#

pencil

#

realism

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: This is "Grazing Cattle near a Farmhouse," a pencil drawing on paper attributed to Jozef Israëls, likely created sometime between 1834 and 1911. It is currently held in the collection of the Rijksmuseum. Editor: The first thing that strikes me is the gentleness. There is a softness in the strokes, a lightness, as if Israëls wanted to capture not just the image, but the very air of that countryside moment. Curator: Israëls came of age artistically during a time of profound social upheaval in the Netherlands. He was very interested in depictions of working class and rural life, reflecting the Realist and later Impressionistic movements, with empathy. We have to ask: who are these grazing animals for, who benefits? The animals' sustenance directly connected to human industry. Editor: Yes, and I see visual echoes here of other art historical pastoral scenes—it places farm life on this seemingly timeless, mythic plane. I am interested in the simple, almost archetypal form of the farmhouse in the drawing. Can it be understood as the hearth of a culture or community? Curator: The farmhouse becomes emblematic. In the context of late 19th-century Holland, rural imagery functioned as a locus of national identity formation, especially when urbanization caused feelings of cultural fragmentation. Think of the cultural associations loaded onto 'the farm', versus any individual farmer's lived experience within larger power structures. Editor: Are those associations still with us today, though? In the details of the pencil work I can sense echoes of, say, a later Romanticism in the rendering of light across the composition; it feels familiar. Are these visual themes also communicating something fundamental to the viewer on a personal, perhaps subconscious, level? Curator: The question is, can such rustic scenes offer space for viewers to reflect on current conversations around food, environmentalism, labor? Or are they ultimately consumed as sites of nostalgia for an idealized rural past? Editor: Perhaps, like all potent symbols, it’s in its multifaceted ability to generate distinct meaning through time that its power really lies. Curator: Precisely. Its value, as you mentioned, seems dependent on its endless reinterpretation.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.