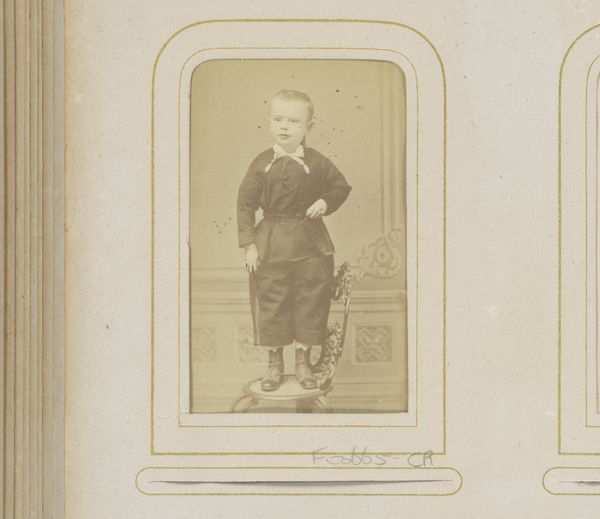

photography, gelatin-silver-print

#

portrait

#

photography

#

gelatin-silver-print

#

realism

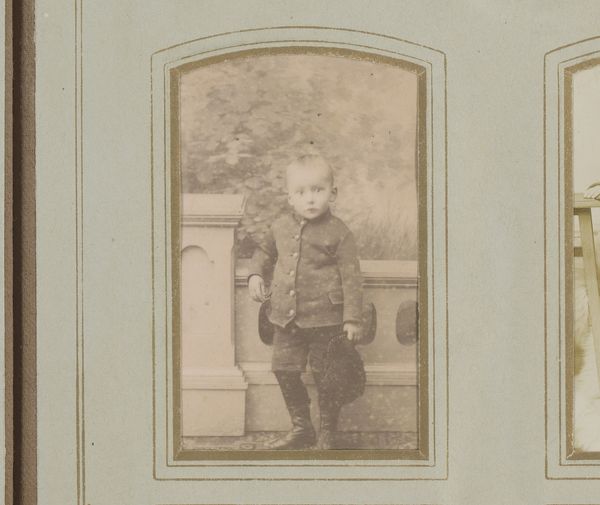

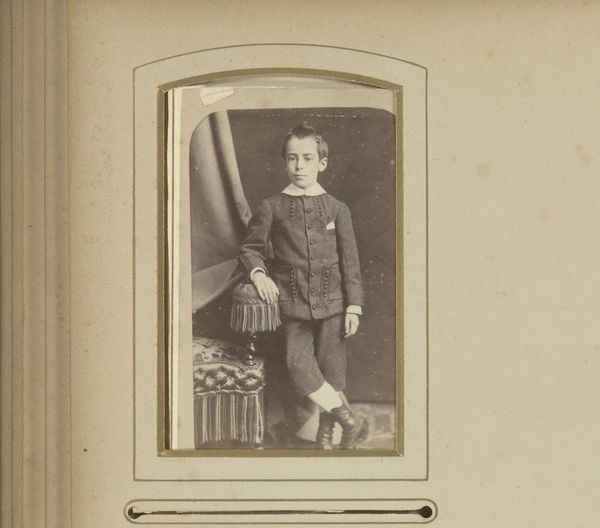

Dimensions: height 84 mm, width 51 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: This gelatin-silver print, entitled "Portret van een jongen, staand bij een zuil," or "Portrait of a boy, standing by a pillar," comes from the Atélier Siewers, and we estimate its creation between 1895 and 1920. Editor: It strikes me immediately how staged the image feels. The boy, the pillar...it all seems carefully arranged, doesn't it? There's a real stillness to it. Curator: Yes, these studio portraits were highly structured affairs. The pillar lends a sense of classical respectability. It elevates the sitter, aligns him with established traditions of power and permanence. Think of the photographic marketplace; presenting yourself with these symbols of stability mattered. Editor: And what about the boy's clothes? That striped sweater seems quite ordinary in contrast to the pillar, doesn’t it? Perhaps the clothes show something about industrialization, as a kind of early mass production that juxtaposes high class with everyday attire? Curator: That's a great point! The attire situates the boy within a specific social context. It’s a marker of the rising middle class. It humanizes him while that pillar implies aspiration, a potential for upward mobility communicated via studio staging. Editor: I'm also curious about the gelatin-silver printing process itself. Consider the labor involved, from preparing the emulsion to the final print. What narratives are embedded within its creation? And who decided this pillar? Who transported it into the space? How often was it employed? What kind of control did it provide? Curator: Precisely. The gelatin-silver print, popularized in the late 19th century, made photography more accessible and allowed for mass production of images. This technological advancement democratized portraiture to an extent, impacting both the artist's craft and the broader consumption of photography. Editor: Seeing how readily available gelatin-silver printing became makes one think of consumption of the sitter, the presentation, the studio's staging - the labor is not solely focused on the subject matter. Curator: Definitely. It allows us to consider photography not just as art, but as a social and cultural practice embedded with political undertones. Editor: Well, now I find the portrait's arrangement far more intricate, beyond a simple depiction, thinking about the whole framework through labor, material and studio practices. Curator: Indeed. It highlights the crucial, multi-layered relationship between technological innovation, aesthetic choices, and social positioning.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.