drawing, pencil

#

portrait

#

pencil drawn

#

drawing

#

16_19th-century

#

pencil sketch

#

pencil drawing

#

pencil

#

pencil work

#

academic-art

#

realism

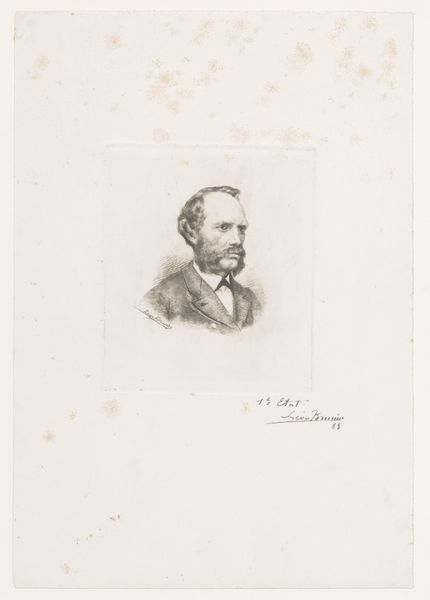

Dimensions: height 150 mm, width 110 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

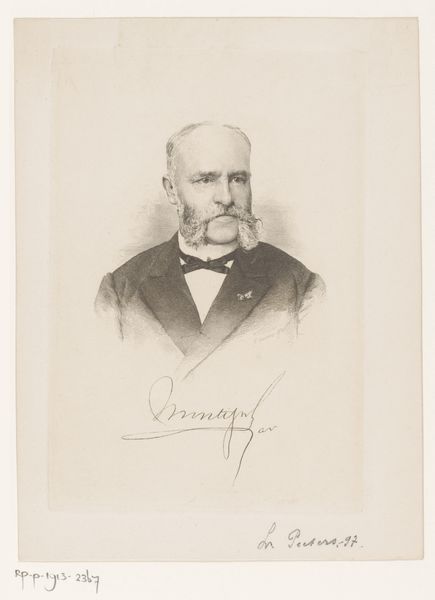

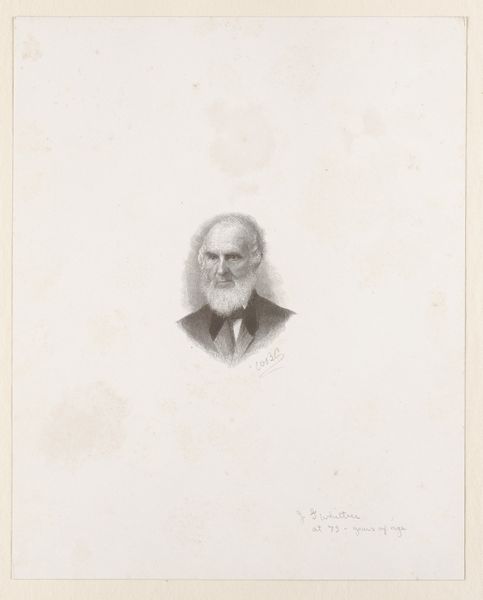

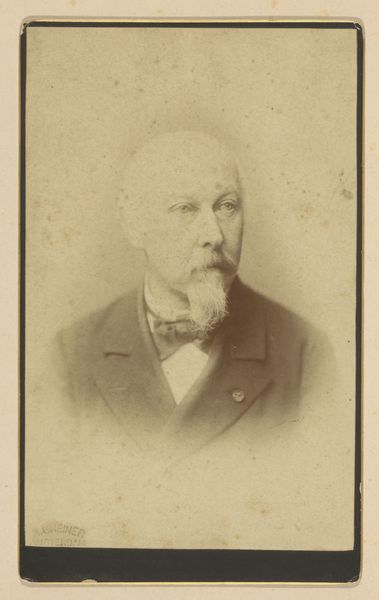

Curator: So, we have here Louis Peeters’ “Portrait of an Unknown Man, Possibly Montigny,” created in 1897. It’s a pencil drawing on paper, a study in serious concentration, wouldn’t you say? Editor: It certainly evokes that air. Immediately, I’m struck by the precision of the strokes, how diligently the artist has rendered texture, especially within that magnificent, sculptural facial hair. One wonders how many pencils were sharpened to achieve this density. Curator: True! And those meticulously detailed whiskers almost upstage the gaze, which I find to be the true focal point. I get a sense of him seeing everything, yet revealing nothing. I wonder what he thinks of us now? Editor: Considering this was made near the close of the 19th century, the labor embedded within such a portrait speaks to broader shifts in artistic production. While academic portraiture upheld status, a work like this seems to hint at a tension between accessible reproduction and exclusive commissioning. What level of luxury was involved? Curator: Perhaps Peeters captured the subject just before a pivotal life change, standing at the precipice of something big or perhaps…just caught him on a Tuesday. To be serious, while the labor involved and socioeconomic contexts do matter immensely, it's important to also recognize that maybe Peeters was just having a particularly engaging Tuesday, himself, drawn in by the quirks and lines that comprise another human's story. Editor: You make an important point about not diminishing creative curiosity. Thinking about access—pencil, paper, the time— it feels less overtly exclusive than, say, oils, but still speaks volumes about the structures that facilitated artmaking, or the pursuit of certain subjects at that time. Even ‘being seen’ then had levels of privilege attached. Curator: So well said, thinking about the level of privilege in being observed! And in being captured... So next time we stroll the boulevard or even visit an ancestral home, it would behoove us to recall this portrait and to also see, capture, and immortalize those figures so often unregarded, yes? Editor: Absolutely! Because, in looking more closely at material histories, we start to see the subtle architectures that uphold or exclude…

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.