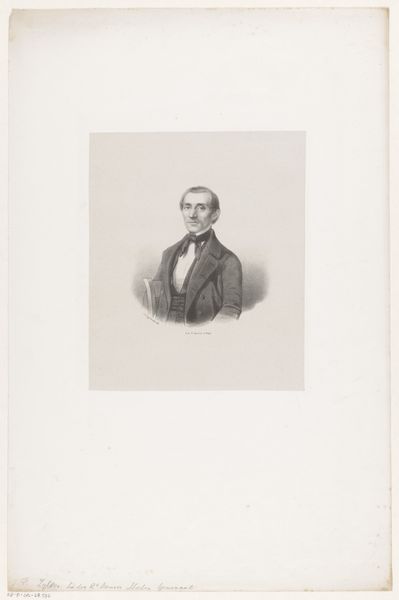

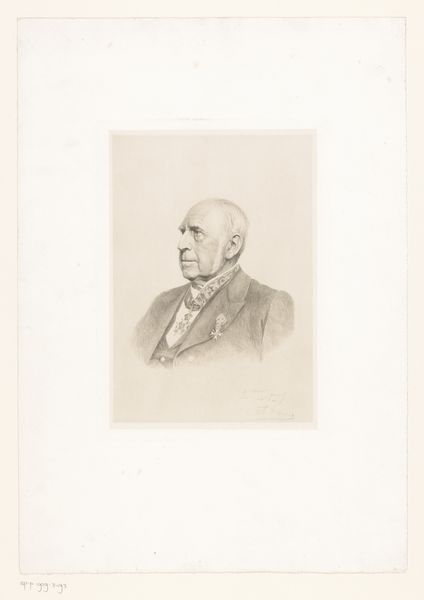

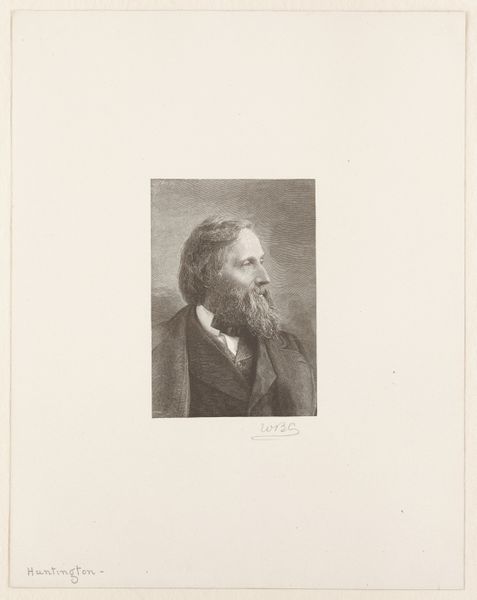

Portrait of Dr. Henry Whitney Bellows c. 19th century

0:00

0:00

drawing, print, wood-engraving, engraving

#

portrait

#

drawing

# print

#

pencil drawing

#

romanticism

#

united-states

#

academic-art

#

wood-engraving

#

engraving

#

realism

Dimensions: 4 x 3 3/16 in. (10.16 x 8.1 cm) (image)12 x 9 1/2 in. (30.48 x 24.13 cm) (sheet)

Copyright: Public Domain

Curator: Here we have a portrait of Dr. Henry Whitney Bellows, created circa the 19th century by William B. Closson. It’s a wood engraving. What are your first thoughts? Editor: There's a wonderful stillness to it. The precision of the engraving really lends itself to a mood of quiet contemplation, even a touch of severity, which fits well with the era, wouldn't you say? The making looks incredibly demanding. Curator: Absolutely. The engraving was likely commissioned. Bellows was a prominent Unitarian minister and social reformer; portraits like these played a crucial role in constructing and disseminating a public image. The art world’s elite were frequently captured in drawings and engravings. Editor: It's fascinating to consider the labor involved—the engraver meticulously carving into the wood block. Each line represents a deliberate decision, translating the likeness into a printable matrix. I imagine this was part of a wider production process? Curator: Precisely. Multiple impressions could then be made, allowing the image to circulate broadly, reinforcing Bellows's status and influence. Consider the political and social role of lithography when mass media didn't yet exist. Editor: It almost feels like a precursor to mass media, creating accessible and reproducible imagery. There’s the fine-grained texture achieved by Closson that’s fascinating from a maker's point of view. How did they translate the subtlety of light and shadow using only lines? Curator: That level of skill contributed to the value of the artwork, demonstrating the engraver’s technical abilities and elevating the print to an object worthy of collecting. As an artifact it is really embedded in social conditions. Editor: Yes, it bridges the gap between craftsmanship and fine art. Understanding the materials—the wood, the inks—and the meticulous, often undervalued work of the engraver helps us appreciate the print's tangible connection to its time. Curator: Reflecting on how imagery shaped public perception, while you contemplate the labor behind its creation—it gives this work resonance. Editor: I find the tangible process offers access into its history—really engaging with what it meant to produce and share in the nineteenth century.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.