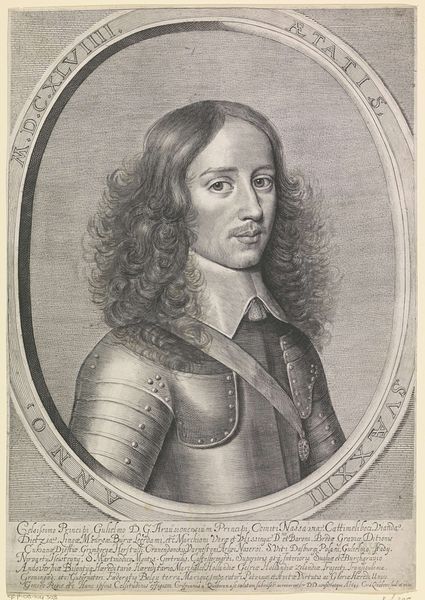

Portret van Willem Frederik, graaf van Nassau-Dietz 1640 - 1645

0:00

0:00

crispijnvandenqueborn

Rijksmuseum

metal, engraving

#

baroque

#

metal

#

old engraving style

#

figuration

#

form

#

history-painting

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 413 mm, width 292 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Editor: So, here we have "Portret van Willem Frederik, graaf van Nassau-Dietz," created between 1640 and 1645 by Crispijn van den Queborn. It’s an engraving on metal, currently held at the Rijksmuseum. I’m struck by how formal and somewhat idealized the portrait feels, yet the subject's gaze is very direct. What’s your take on this work? Curator: It's essential to see this within the context of 17th-century Dutch society, where portraiture was less about capturing pure likeness and more about constructing identity. The engraving itself signifies accessibility; printed images allowed the dissemination of status and power beyond the elite circles who commissioned painted portraits. Who do you think was this image directed towards, considering its inscription? Editor: The inscription seems quite detailed, perhaps for a more learned or politically aware audience? It seems almost like a dedication with all the Latin. Curator: Exactly. Think about the rise of the Dutch Republic and its constant need to legitimize its leaders. Images like this engraving, with its Latin inscriptions emphasizing Willem Frederik's lineage and titles, functioned as propaganda, bolstering his position within a complex socio-political landscape. The armor, the lace, even his expression—all contribute to an image of authority and legitimacy carefully constructed for public consumption. Do you see how the technique amplifies this feeling? Editor: I see what you mean. The engraving is so precise and detailed, lending it a sense of authority and permanence. It's not just a picture, it’s a statement. Curator: Precisely. These images circulated widely, shaping public perception and reinforcing existing power structures. Editor: I hadn’t considered the print as a tool for political messaging! I guess I’ll never look at portraits the same way again. Curator: It reveals how even seemingly straightforward images play a role in broader historical narratives, something crucial to understand to make art accessible for all.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.