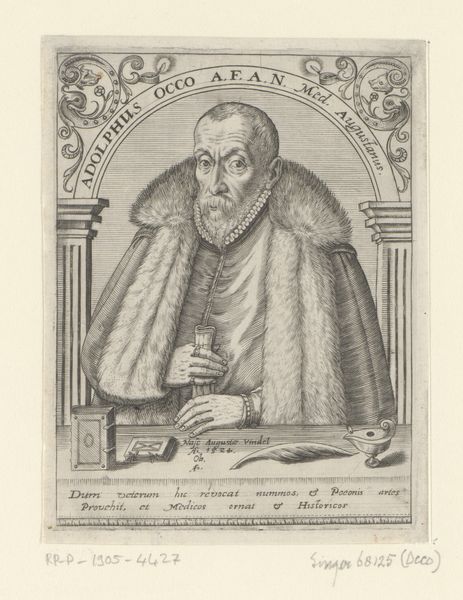

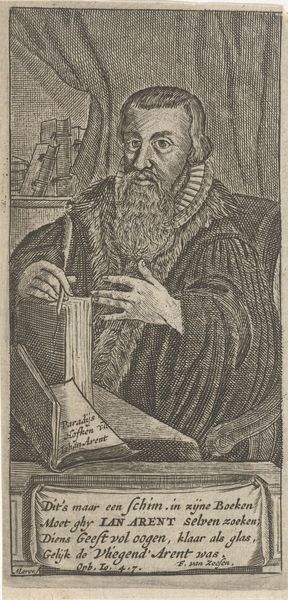

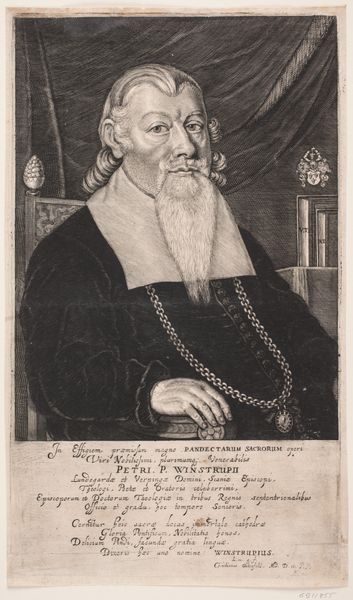

Portrait of a Man, Possibly Jean de Langeac (died 1541), Bishop of Limoges 1539

0:00

0:00

painting, oil-paint

#

portrait

#

painting

#

oil-paint

#

11_renaissance

#

history-painting

#

northern-renaissance

Dimensions: 47 1/4 x 34 1/2 in. (120 x 87.6 cm)

Copyright: Public Domain

Curator: Standing before us is a rather imposing portrait from 1539, currently known as "Portrait of a Man, Possibly Jean de Langeac," Bishop of Limoges, held here at The Metropolitan Museum of Art. It's rendered in oil. Editor: My immediate impression is one of weighty authority. The somber color palette and the direct gaze, combined with his prominent attire, creates a very powerful presence. There's almost a sense of... foreboding, wouldn't you say? Curator: Yes, definitely. It adheres to Northern Renaissance portraiture conventions, emphasizing status through details. Langeac, if it is indeed him, was a significant figure in the French church and, briefly, a diplomat, so this gravity suits the role. Note the hourglass – a memento mori, reminding us of time's passage and our mortality. It's a common feature in portraits of the era, a statement about his intellectual concerns and, inevitably, social rank. Editor: That hourglass jumps out for me too. Placed next to his books and documents, the association of power and knowledge takes center stage. The composition definitely steers viewers to read his wisdom first and maybe something else later, but knowledge first! What about that sumptuous fur? A marker of opulence but what does that suggest to the viewer then and now? Curator: Absolutely, it symbolizes wealth and power but think about what having and commissioning a painting of yourself like this said, what message it sends about Langeac's, or possibly another patron, societal position in life? As an ecclesiastical leader, his appearance needed to broadcast dignity and learning. Editor: Precisely. The power dynamics implicit are interesting. His gaze isn’t quite confrontational, but it's firm. Consider the context of religious upheaval at the time, what he sought to convey about his steadfast role in a fractured world! Also note his hands clasped are interesting–they create a frame. There is intentional composition to his hands that emphasizes how one ought to approach him. What that does is remove personal interactions and favors societal approach. It underscores just how curated and self-aware these Renaissance portraits are as exercises of social marketing for a select, often exclusively male, demographic. Curator: A sharp insight! And from an art historical standpoint, consider the artistic skill involved in rendering those minute textures of fabric and skin, and conveying this intensity within the man's face through oil on panel. This tells us not just about Jean de Langeac himself, or whoever this sitter may be, but of Renaissance artistic values during an era of significant change. Editor: Agreed. I’m really struck by what this portrait is saying today in relationship to what he believed about himself. Looking closely, one must ask what happens when these markers of power are taken from figures that aren’t typically framed as holding the same political agency as this “man.” The message it provides, whether about power and mortality or political upheaval is quite intriguing and lasting, particularly as we reassess art histories with intersectionality. Curator: Indeed, reflecting on the intersection of personal expression and social position leaves us with far more to consider beyond just artistry. Editor: It definitely does—portraits allow us to confront, even centuries later, questions about who held power and the stories we’ve inherited through history.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.